The Economist reports on an interesting new study undertaken on differences in gender pay:

According to data for 8.7m employees worldwide gathered by Korn Ferry, a consultancy, women in Britain make just 1% less than men who have the same function and level at the same employer. In most European countries, the discrepancy is similarly small. These numbers do not show that the labour market is free of sex discrimination. However, they do suggest that the main problem today is not unequal pay for equal work, but whatever it is that leads women to be in lower-ranking jobs at lower-paying organisations.

The figures for Britain in the study break down as follows. The “raw” gender pay gap between all men and women is 28.6 percent. This falls to 9.3 percent once one controls for people being in the same level job. This falls further to 2.6 percent for the same level job at the same company, and to just 0.8 percent for the same level job at the same company with the same function. In other words, as free market economists have long explained, there is little to no evidence of overt company discrimination once one controls for observable factors (and beyond those here, things such as educational attainment, or years of continuous work experience).

Confronted with studies such as these, some commentators, and even some libertarians, pivot. They suggest that this kind of research attacks a straw man. Few people think it’s overt wage discrimination at an employer level that’s the problem, they say. The aggregate statistics though, which show women on average earn 82 percent of men’s median hourly earnings, are said to reflect other types of structural societal discrimination – in the subjects that young women are encouraged to study, hiring processes at firms, the nature of wage negotiation and much else besides.

The starting point that we would expect an aggregated pay gap of zero even in a world in which no overt or covert societal pressures exist is questionable. When free to choose, it’s unlikely gendered populations will make equal choices. And to the extent these commentators are right, it is unclear what the policy implications should be.

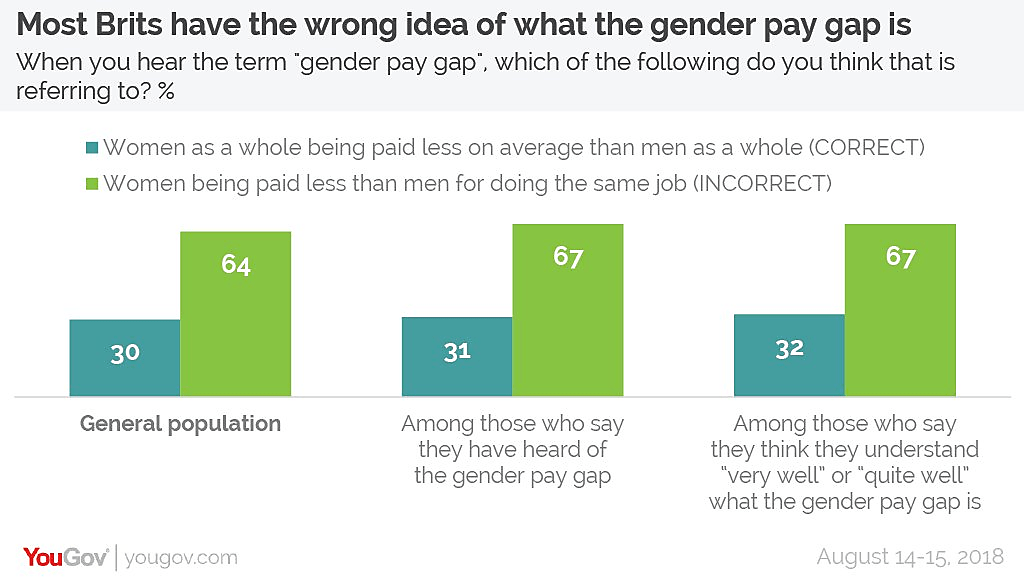

Nevertheless, most evidence suggests this is explicitly not what the public hear when they see talk about the gender pay gap. A recent YouGov survey in the U.K. asked the public what they thought when they heard of the term. Just 30 percent said that they thought it was about women, on aggregate, being paid less than men. A whopping 64 percent thought that it was about women being paid less than men for the same job. To be clear: the latter is not what the commonly cited aggregated statistics on the gender pay gap are about.

Politicians appear to misunderstand this too, and it leads to bad policy. After all, in developed countries one policy that they have pushed for is company-level disclosures– something that makes little sense if you are worried about society level structural problems.

It’s little surprise that the public interpret the term in this way then. Though in pure language terms both definitions might be acceptable, pay gap stories of the aggregate variety reported in the media regularly include irresponsible lines implying discrimination, such as “from this day onward, women work for free” or describe companies that have the largest gaps as “the worst offenders.”

In this environment of misinformation, it is important and worthwhile to continuously highlight what the pay gap shows, and what it doesn’t. The structuralists might have a point about broader drivers, but it’s not one helped by a raw measure that is used misleadingly and to advance policy positions which do not make sense according to the structuralist concern.