Leaders of the G‑7 countries agreed on the weekend to pressure other countries to impose corporate tax rates of at least 15 percent. They also agreed to reallocate the earnings of some multinational corporations if too much was deemed to be in low-tax countries. The impetus for the agreement is a claimed revenue shortage caused by corporate tax dodging, especially by large technology companies. The G‑7 countries are Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, and the United States.

At the G‑7 meeting, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen alleged that the agreement would “end the race to the bottom in corporate taxation and ensure fairness for the middle class and working people in the US [and] around the world.” And she said recently that a global minimum corporate tax is “about making sure that governments have stable tax systems that raise sufficient revenue.”

A Bloomberg story fawning over Yellen said the new agreement “would signal an end to decades of nations racing each other to lower levies, eroding their collective revenues.”

However, Yellen and the reporters who cover her should look at the data. It does not show eroding or insufficient revenues overall.

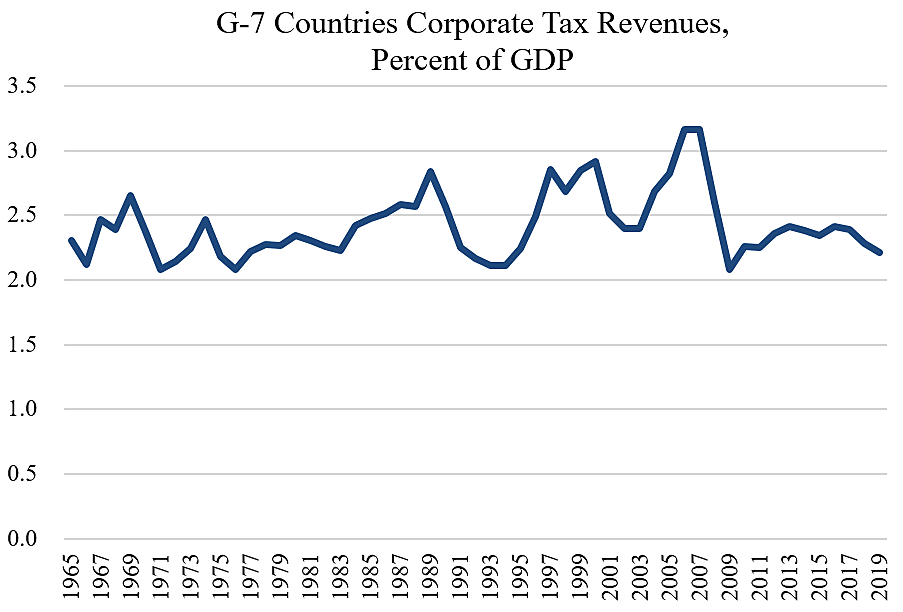

The chart below shows corporate tax revenues as a percent of GDP for the G‑7 countries from 1965 to 2019. Despite huge increases in cross-border investment, the rise of the Internet, and the mobility of modern industries, corporate tax revenues have hovered in roughly the same range for half a century, although with fluctuations from economic booms and busts. The data is from the OECD.

The long-term stability of corporate tax revenues is remarkable given the large changes in the global economy and the fact that corporate tax rates have plunged since the 1980s. The average federal-state corporate tax rate in the G‑7 was around 50 percent from 1965 to 1985, and then started to fall, ultimately reaching 28 percent by 2019. Similarly, tax rates have fallen since the 1980s for a broader group of 22 countries, yet tax revenues are up.

Yellen is leading a tax-hike crusade based on a false narrative. G‑7 countries have not been starved of tax revenues. Rather, leftist politicians aiming to expand government want to pave the way for large tax increases down the road. To do that, they need to squelch competition from countries with sensible lower-rate corporate taxes such as Ireland. Ireland’s corporate tax rate is 12.5 percent.

With the new agreement, the German finance minister said that Ireland needs to “get on the train.” But Ireland’s tax reforms and economic success should be emulated by other countries, not condemned. After all, the OECD’s own economists concluded, “Corporate taxes are found to be most harmful for growth” of all the major taxes. Ireland has taken that sound tax-policy advice and implemented it. Germany and other OECD countries should get on that pro-growth train.

The G‑7 agreement goes in the wrong direction by trying to entrench higher rates for the “most harmful” tax. Yellen and the other G‑7 leaders aim to create an international cartel to squelch tax competition and keep government costs high, just like the OPEC cartel tries to squelch competition and keep oil prices high.

America’s role in the world economy should be to foster competition, not to join monopolistic cartels aimed at punishing smaller countries adopting commendable tax reform policies.

Data notes: The average federal-state G‑7 corporate tax rate in 1980 was 50 percent. I do not have state-level rates before 1980, but the average federal rate for the G‑7 varied only slightly between 1965 and 1980.

Further comments on these issues here, here, here, and here.