If anyone thought that the defeat of Proposition 15 last November meant that debate over the future of California’s landmark property tax limitation Proposition 13 was over, they are almost certain to be mistaken.

1978’s Proposition 13, which was in many ways the harbinger of a nationwide property tax revolt, limits property taxes to no more than 1% of purchase price, with increases capped at 2% annually. Last year’s Proposition 15 (the proliferation of numerically identified California ballot measures can be confusing) would have superseded parts of Prop. 13. The changes would allow most commercial property to be taxed at market value, as opposed to purchase price, , while retaining the previous rules for residential property, a process known as “split roll.” In practice, this would have resulted in much higher taxes on affected properties, because most commercial property tax assessments would increase. The measure was defeated narrowly but decisively, 52 to 48 percent.

Still, in California, ballot measures have a way of coming back from the dead. In November, in fact, voters were asked to take a second bite at the rent control apple, having rejected a ballot measure in 2018. (They rejected it again this time). Voters also replayed a vote on changes to property tax assessments of inherited homes, and a guarantee that most new revenue would go to a fire safety fund. The measure, which had been rejected in 2018, passed this time by a 51% too 49% margin.

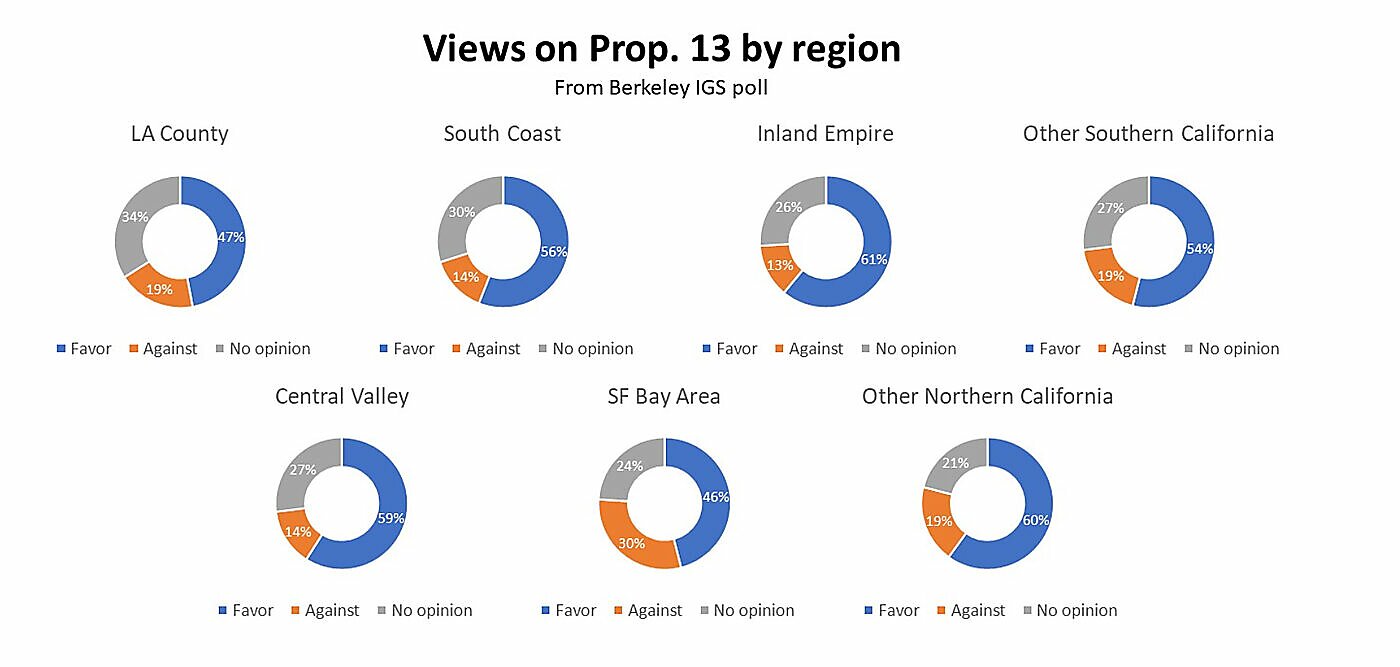

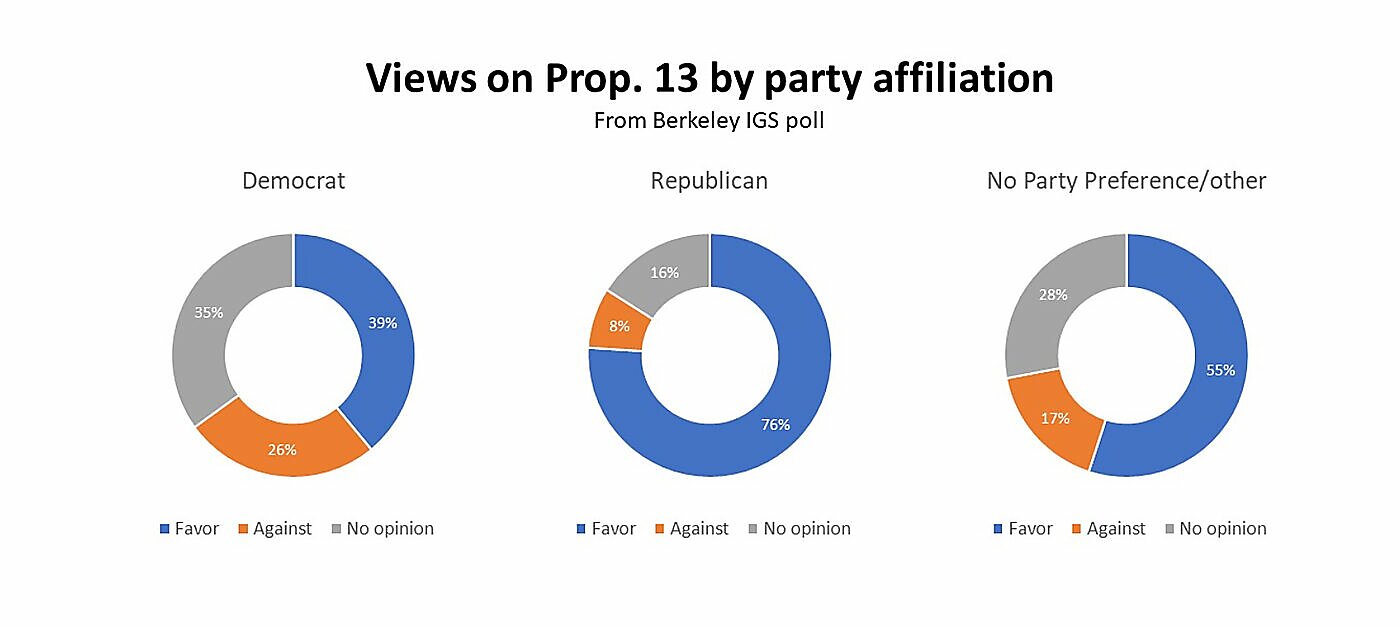

The core concept of Proposition 13 – a limit on property taxes — remains popular. Polling from UC Berkeley shows that voters across the board are hesitant to tinker with Prop. 13, with 53% saying they would vote for Prop. 13 if it were on the ballot today. But that top-line number understates the breadth of support for Prop. 13. Pluralities of voters in each of the state’s regions, with each partisan affiliation, and even non-homeowners who do not directly benefit from Prop. 13 continue to favor it.

The Berkeley polling also shows that 78 percent of California voters think taxes are pushing businesses and individuals to leave the state, and 81% describe taxes as high. These are an astonishing figures, and show why recent stories about tech firms and entrepreneurs moving to Texas have gained so much traction. Notably, the Berkeley polling pre-dated this most recent round of “California Exodus” stories: Californians’ sense that the business climate is unwelcoming stems from a deeper sense about the state’s government, not the news cycle.

Still, there remain reasons to question the continued utility of Proposition 13. For example, by limiting revenue that localities can receive from new construction, Proposition 13 may be contributing to California’s housing shortage. Most disconcertingly for commercial property, the system allows lower taxes for longstanding property owners than for relative newcomers, creating an uneven playing field for commercial landowners and the businesses who rent from them. Moreover, California’s property tax rules have led the state to lean more heavily on sales and income taxes than property taxes. We’ve written about this elsewhere, and our colleagues have noted the current reliance especially on income taxation leads to significant volatility and hinders long-term planning.

And local officials will undoubtedly make the case that COVID has wreaked havoc on state and local budgets, making new sources of revenue necessary. We should not, therefore, expect the defeat of Proposition 15 to be the last word on the subject.

However, before launching another bid to undercut Proposition 13, supporters of the split roll have some important questions to answer.

For example, is new revenue really needed? As we previously noted, Proposition 13 has not resulted in a decrease in local government spending. Before the coronavirus crisis hit, California had a projected budget surplus roughly the same size as what the split roll changes were projected to bring in. Although that surplus has now been dissipated, we do not yet know the length or depth of the pandemic’s economic fallout. And, if the economy remains slow, is that time to be considering new taxes on struggling businesses?

In addition, California has only recently begun implementing significant new changes to its education finance system through the Local Control Funding Formula. This reform further disconnected school districts’ revenues from local property taxes. In some districts, especially high-poverty districts with lower property tax revenues, that is probably a good thing. But split roll, especially if the money were directed to education, as Prop. 15 would have done, would cut against the recent reforms in California’s school funding.