(Today we celebrate the great Walter Grinder’s 80th birthday by reposting our tribute to him on his 75th.)

Walter E. Grinder turns 75 years old today [80 now!]. He is the former CEO of the Institute for Humane Studies and President Emeritus of the Institute for Civil Society. Walter has been an important mentor to several of the contributors to the Free Banking blog [Alt-M's predecessor] and many other people interested in Austrian economics, spontaneous order in human society, classical liberalism, and modern libertarianism. Happy birthday, Walter!

Several of Walter Grinder's friends and colleagues were kind enough to write tributes in his honor below. Also, read Leonard Liggio's biography of Walter and view photos.

John (and Christine) Blundell, formerly of the Institute for Humane Studies and the Humane Studies Foundation

I think I met Walter E. Grinder in the summer of 1975 at an IHS conference in Hartford, Connecticut led by D. T. Armentano with newly minted Nobel F. A. Hayek in attendance. It was the second of three meetings to reinvigorate Austrian economics.

Soon after, back in London, I founded the Carl Menger Society for the study of Austrian economics and Walter was a year or two later just across the Irish Sea at the University of Cork with Professor David O'Mahony.

They were a great asset as I built seminar programs and one day conferences in London around them.

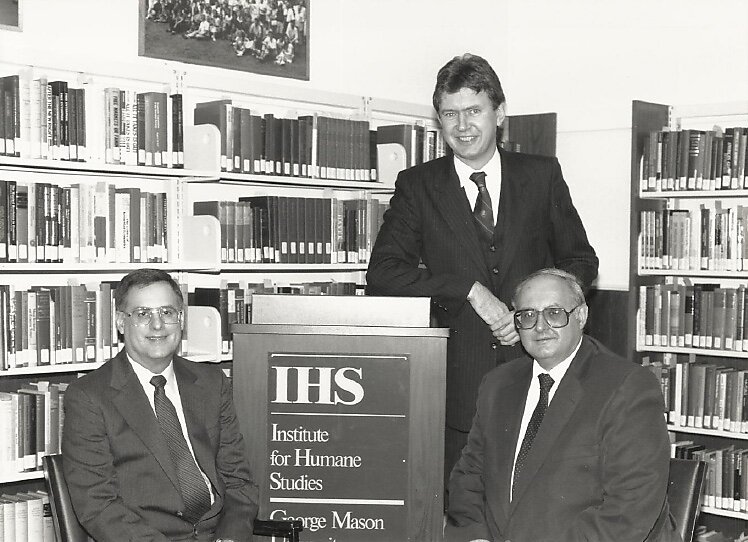

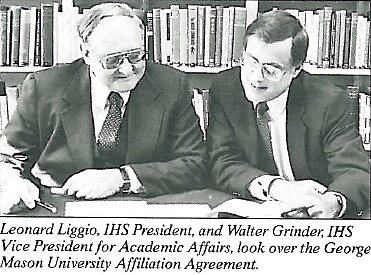

In 1981 Walter moved to join Leonard Liggio at the Institute for Humane Studies in Menlo Park, California. Leonard was President and Walter was Vice President and ran the programs. In late 1981 Leonard invited me to join as Director of Public Affairs charged with making IHS famous -- I landed at SFO on St George's Day (23 April) 1982.

What a blessing to work side by side with the two greatest talent coaches in the history of classical liberalism!

But within weeks I realized IHS was in crisis, complete meltdown -- it was broke.

We had a wretched weekend Board retreat out at Half Moon Bay. I can recall Charles Koch, J. P. Humphreys, Bill Law, Harry Hoiles, and Art Neis with me, Leonard, and Walter. There were probably others.

It was a nightmare. My wife and I had given up well-paying jobs in London and, with a baby on the way, here we were with her not allowed to work and me effectively a wet-back at a bankrupt company. I did get my green card eventually. But there had been zero staff preparation for this meeting and we got thrashed!

So what happened? In no order:

- We slimmed down the payroll;

- I moved from public affairs and became Executive VP responsible for fundraising and everything else except program;

- Leonard stayed as President but Walter became CEO -- not many people know that;

- And we moved from Menlo Park, California to George Mason University in northern Virginia thanks to Rich Fink and Charles Koch.

But most important of all, we ditched everything we did (for example, we owned two warehouses of books somewhere, which I sold to Andrea Rich at Laissez Faire Books) except for one thing: "the discovery, development, and support of young people who share our interests and concerns and who are intent on careers that will make a difference."

We called it the DDS model, as in "discovery, development, and support." Walter contributed two of these active verbs and I contributed the third sitting on a sofa in Leonard's office.

We ditched all the crap. We had a magical run of years from bankrupt and mission-less to totally focused with 20% annual growth on every measurable front with solid reserves for, say, seven straight years.

Walter did what he was born to do, namely to run the programs.

Leonard did what he was born to do, namely be Leonard.

And I was free to hire the staff, raise the money, and keep my heroes free from of crap and stress. And also handle the PR and public affairs.

In the fall of 1988 the Board -- at Walter's request -- appointed me as his replacement as CEO, and Leonard became Distinguished Senior Scholar so I could also assume the Presidency. These kinds of moves were so typical of Walter who, I can reveal, confused the Board at least once by refusing a pay increase!

My wife of 36 years, Christine, bonded with Walter and they were a remarkable team with three phases to their cooperation. Chris had been a tenured professor of statistics back in the UK by the way.

First, in Menlo Park IHS had started the Claude R. Lambe Fellowship Program (through the generosity of Charles Koch) with serious scholarship money that attracted a lot of applicants. Walter recruited Christine to read all the files and write evaluations. She was not allowed to be paid, but after the "lambing season," as we called it, I got to take her out to one of the best restaurants in the Bay Area for dinner.

Second, we got to Fairfax, Virginia on Labor Day weekend in 1985. Walter hired an assistant -- I forget her name. After three months she took her last Friday of the month paycheck, walked out, got in her car, and drove away. On the next day at the office Walter asked me if he could hire Christine. We had a separate foundation called the Humane Studies Foundation (HSF) of which he was President and I was merely Secretary. Christine would work for him at a separate company. Go for it, I said, and the next day, Sunday, he hired her and she started Monday right as the next "lambing season" was due to start.

They were a really terrific partnership. To me the 1986-1993 Walter/Christine era is very special indeed. The talent crop speaks for itself.

The third phase came after I became CEO of the Institute of Economic Affairs in London (1993-2009). Walter left IHS to establish the Institute for Civil Society.

With the advent of e-mail, Chris and Walter continued to collaborate as she ran ICS programs for Walter's choice students in the US and Europe. They ran many programs for Walter's top draft picks during the rest of the 1990s and into the 2000s, I recall.

Today Walter does us all a great service with his at times daily e-mails alerting us to his latest discoveries or insights.

Walter does not travel much, but he pours his advice into young talent so they will go further, faster. Walter sticks to you like glue, following you and guiding you. In return his alums are so grateful that even the very busy ones with high opportunity costs will journey south to Mountain View for a cup of coffee with Walter whenever they are in San Francisco.

I certainly appreciated his very astute advice on my last but one book: Ladies for Liberty: Women Who Made a Difference in American History (March 2013, expanded 2nd edition).

Walter, Christine and I send you both our heartiest congratulations on your ongoing professional achievements and our love to you and your family from all of us on your 75th birthday.

Daniel Klein, Professor of Economics, George Mason University

Dear Walter,

The sons and daughters of liberalism strive to make their mark and secure a place in the world. But they seem to have difficulty maturing into fathers and mothers of liberalism. The liberal network seems to be one of sons and daughters, not fathers and mothers.

That might be in part because life in academia doesn't lend itself to parenting in liberalism. When we met around 1980, you must have been 42. When I think of 42-year olds today, they seem to be still preparing for their bar and bat mitzvahs. You seem to have skipped over the phase of son entirely and moved directly into fathering.

I am grateful to you for — besides being such a good friend to me and my family — helping me to find a sustainable existence as a son of liberalism, but also for your courage and generosity in assuming the role of father. Otherwise I would have been largely fatherless. You've allowed me to enter into seeing as you see, and that, I feel, has helped me to see how those who responsibly assume a most extensive responsibility see. Thank you Walter. Warm wishes on your 75th birthday.

Sincerely,

Dan

Kurt Schuler, Senior Fellow in Financial History, Center for Financial Stability

Though we have been on opposite coasts for many years now, I continue to benefit from your wide-ranging mind. You know what few others know and make intellectual connections few others can make. Your published writings, as good as the best of them are, are just the tip of the iceberg. You have exercised influence many times greater through well-chosen words or, nowadays, e-mails of advice; your knowledge of scholars themselves as well as of their scholarship; and your generosity in sharing the classical liberal tradition. Your mentoring of young (and no longer young) scholars has been significant in making the tradition a living, vigorous one able both to absorb and to generate new ideas.

Andrea Millen Rich, President, Center for Independent Thought

Walter, it's hard to believe I've known you, admired you, laughed with you, done work for you — for 40 years. Can you really be that old???

You're obviously a lynch-pin of classical liberal scholarship through the years. I'll let those more involved and knowledgeable speak to that.

Take pride in all the work you've done, all the scholars you've nurtured and inspired, all the way back to…well, I don't know back to where because I only know you as far back as Libertarian Scholars Conferences and CLS. Enjoy being an old codger, a father, a grandfather, and a true friend – to me, to all of us who are crazy for you.

Keep on keepin' on, dear friend,

Many hugs,

Andrea

David Beito, Professor of History, University of Alabama

I first came into contact with Walter Grinder while I was a first-year graduate student at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in the early 1980s. While it was before PC had gained a stranglehold, and my (often Marxist/New Left) professors were generally open-minded, the history department could still be a very lonely place for a young libertarian. Walter was instrumental in giving me the necessary self-confidence to navigate my way through. When I faced a historical or theoretical conundrum, or simply wanted some references to leading work in a field, I rang up Walter. I always felt better as a result. Few people were better able to shed new light on a question that many of my professors, and fellow graduates, considered settled. I remember fondly our long conversations about the role of overproduction, or lack thereof, as a cause of U.S. imperialism. So much new stuff! In his role of outside faculty mentor, Walter was the ultimate “network builder,” always trying to make us aware of others who shared our interests and passions.

After I received my Ph.D., it was Walter and Leonard Liggio who were responsible for

the publication of my dissertation on tax revolts during the Great Depression. Both arranged a fellowship for me at the Institute for Humane Studies, which enabled me to revise the manuscript. Unbeknownst to me, Walter sent a copy of the manuscript to Lew Bateman of UNC Press. Bateman liked the book and got the ball rolling.

Later, after my position was not renewed at the University of Nevada, Walter and Leonard were the only ones who kept my head above water by cobbling together a combination fellowship and “makework” job supervising history students at IHS. Without this lifeline, I may well have dropped out of the profession. In that makework job, I did my best to mentor young history students via long distance in the same way that Walter had mentored me. One of those students was the brilliant Alan Petigny, who died tragically last month. Walter was also key to turning me onto the vast role of mutual aid in history, which ultimately led to my book on fraternal societies and, then, my book on T.R.M. Howard.

I will always be grateful for Walter’s sage and thoughtful counsel, his passion for liberty, including a deep-seated hatred of war which I took to heart, lack of pretense, no nonsense sense of humor, and genuine concern about helping students survive in the profession and become better scholars. He has not only been a mentor for so many of us but a kind of super mentor. In this regard in particular, Walter’s retirement from the Institute for Humane Studies left a gap which nobody has come close to filling.

George Selgin, Professor of Economics, University of Georgia

Dear Walter,

As I reflected upon how I first came to know you, I realized that had it not been for that encounter, my life would have been utterly different than it has been. And I don’t merely mean that you changed my life in the sort of way that a Brazilian butterfly might change the weather in Texas. Your influence was as certain as it was decisive.

It must have been in the late spring of 1981 that I came across that tiny ad in Reason. It was from this place I’d never heard of called the Institute for Humane Studies, and it offered summer research grants. I’d just begun working on a paper inspired by Hayek’s Denationalisation of Money, which I’d read earlier that spring, so I decided to apply. I got the money, which was great. But I also got to know you, which was far better.

You gave me all sorts of advice on the project, in letters and occasionally on the phone (of course we didn't have email back then). It was all good, but I’m especially grateful for your having alerted me to the work of a UCLA grad student on the Scottish free banking episode. His name was Larry White. You sent me drafts of Larry’s chapters, and I instantly became a Larry White fan. Soon I was corresponding with him, asking all sorts of questions. I remember one in particular. It was, “Where do you plan to teach?” I’d already decided to be his student. That’s how I ended up at NYU.

Of course you and I stayed in touch, eventually meeting at the old IHS headquarters in Menlo Park—I think that was when Hans Eicholz showed up on his motorcycle, in full leather kit; he made me wonder whether I was tough enough to be a classical liberal! When I’d finished my NYU coursework, you invited me to come back as an intern. I leapt at the opportunity, thinking it would be a great one for writing my dissertation.

As it happened, from 9 to 5 you guys mostly had me slaving away on IHS stuff—planning seminars and organizing the contact list, among other things. But from 7 until 9 every morning, and again from 6PM til midnight, I worked on “The Theory of Free Banking,” half the time at the (late, lamented) Printer’s Ink at Stanford, and half at the Prolific Oven in Palo Alto. (Do you remember those half-moon cookies they had? Mmm!)

Despite the hours the writing went better than I could have hoped. And that was also mainly your doing, because every morning around 10:30 we walked over to Pete’s for coffee (Major Dickason’s—I still have the mug I bought there, white ceramic with red-brim), and then sat on a nearby park bench to discuss my progress over it. So every idea I put into the dissertation—and plenty that, thank goodness, I didn’t put in—got a dry run. If every doctoral student had someone like you to talk to, there’d be a lot fewer ABDs hanging around.

IHS and I moved to George Mason at the same time—I even got you guys to transport my little Honda Passport for me, only to end up ditching it after an Alexandria policeman politely informed me that Virginia, unlike California back then, insisted on my insuring it, acquiring a special motorcycle license, and wearing a helmet. Miserable tyrants! But at least I had a teaching job, which meant that, instead of just serving as a factotum at them, you actually let me lecture at IHS seminars. I did that until 1995, when, along with all the old-guard faculty, I quit in protest over your leaving the Institute. I know you didn’t want us to do that–the Institute always came first with you–but you shouldn’t blame us: so far as we were concerned, you were the Institute! And though the place now has oodles more $$$ to toss around, I don’t imagine that it will ever replicate the unique brand of intellectual inspiration and encouragement that you were able to give to students like me. If classical liberal scholarship is thriving now, that’s in no small way thanks to you.

Happy Birthday, ol’ buddy. And many more.

________________