That’s what Dick Timberlake originally planned to call the fantastic book that Cambridge University Press has recently published under the modified title, Constitutional Money: A Review of the Supreme Court’s Monetary Decisions.

I’m rather partial to the old title, for it conveys better than the new one does the fact that the basic money of the United States today really is something that has been “made” by the Supreme Court rather than something “Constitutional” in the sense of being obviously permitted, much less expressly authorized, by what is still, nominally at least, the supreme law of the land.

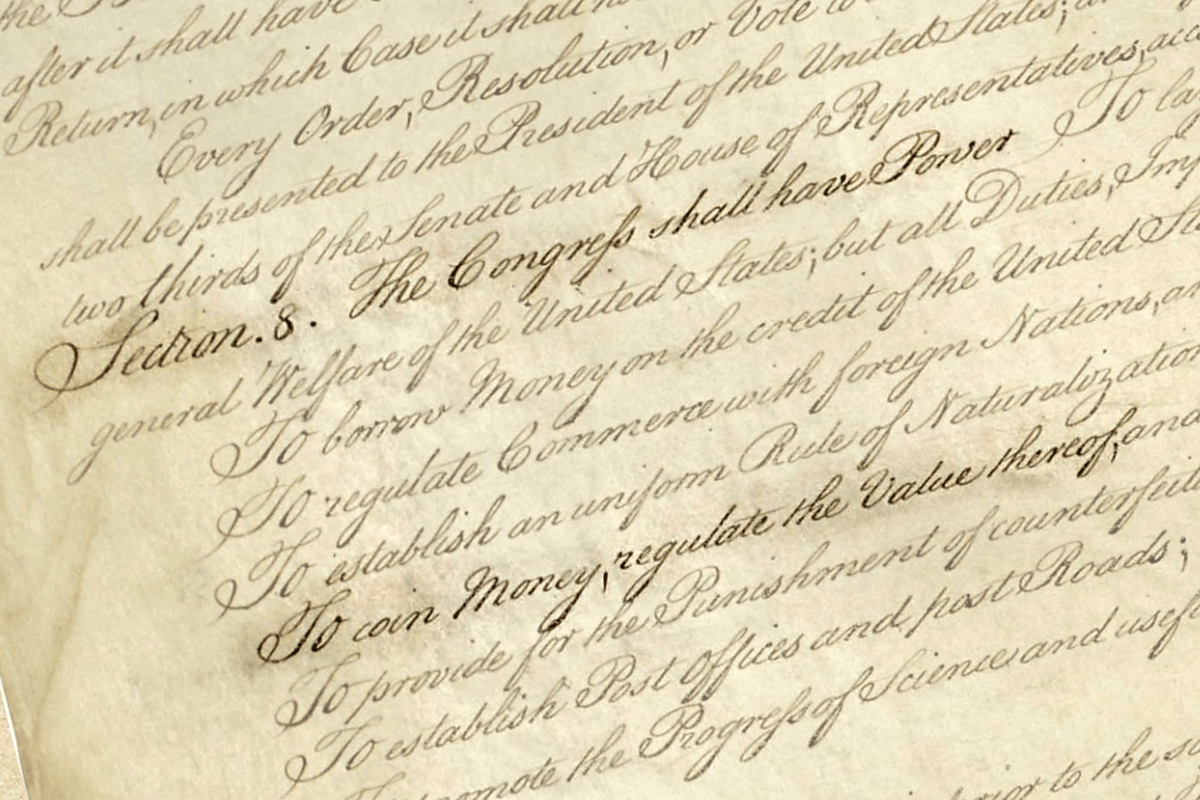

That law contains only two references to money, both of which occur within its first Article. Section 8 of that Article gives Congress the power “To coin Money” and to “regulate the value thereof.” Section 10 in turn declares that “No state shall…coin money; emit Bills of Credit; [or] make any Thing but gold and Silver Coin a Tender in payment of Debts.”

It ought to be perfectly evident, from the writings of the founders themselves, from opinions expressed (according to James Madison’s notes) during the Constitutional Convention, and from the understanding common to all authoritative commentaries on the Constitutional debates, that the overarching objective of these clauses was to guarantee that neither the states nor the Federal government should ever again be able to issue irredeemable paper currency as several colonies, as well as the Continental Congress, had done in order to avoid having to pay their bills with specie. The idea, as Roger Sherman put it at the time, was that of “crushing paper money” once and for all.

Nor, as any competent Constitutional scholar will tell you, does the fact that states alone are expressly prohibited from emitting “bills of credit” or from making legal tender out of anything save gold or silver mean that the founders thought it A‑O-K for Congress to do either of those things. On the contrary: as the 10th amendment was supposed to make clear, in case anyone was dull enough to forget it, the whole point of the Constitution was to set forth those powers that states had elected to delegate to the central government, the others being “reserved to the States respectively” or (if prohibited to the States) “to the people.”

All of which, of course, raises two obvious questions: (1) How did we end up having, as our nation’s official money, Federal Reserve notes–notes which, being irredeemable in gold or silver or anything else, are precisely the sort of “bills of credit” the founders intended to proscribe?; and (2) How did the government manage to make these notes “legal tender for all debts public and private”? Those questions in turn raise a third obvious question, to wit: Where the heck was the Supreme Court while all this was goin’ down?

The answer to the last question is, of course, that the Supreme Court was there all along, torturing the Constitution until it submitted to the decisions that led us where we are today. The details concerning the infernal devices the Court employed to twist and to stretch and eventually to eviscerate the Constitution’s monetary clauses (and, with them, much of the rest of that document’s sinews), the men who wielded them, and those who protested, are the subjects of Dick’s story–a story he tells as only the leading historian of American monetary policy could tell it. And he tells it both with great aplomb and with a rectitude which, in light of the maddeningly perverse nature of some of the sophistries he must contend with, seems in places almost super-human.

According to Timberlake’s retrospective account, it was largely owing to Chief Justice John Marshall’s 1819 decision in McCulloch v. Maryland–a case concerning Congress’s power to charter a bank–that the fiat money camel was able, first to poke its nose, and eventually to force its way entirely, into the Constitution’s precious-metal wigwam. Marshall offered two reasons for holding that Congress did indeed have the power in question. First he observed that “There is nothing in the Constitution that excludes it.” Then, as if he’d suddenly remembered the 10th amendment, he added that the Bank’s constitutionality rested upon Congress’s power to make “all laws which shall be necessary and proper” for carrying out its express powers, as set forth in Article 1, Section 8, and elsewhere. The latter argument, admittedly, also comes to grief if one takes “necessary” to mean “indispensable” or “absolutely required” or “essential,” as dictionaries tend to do. But Marshall had an answer for that, too: “Necessary,” he began by observing, means “convenient, useful, and essential.” Having thus arbitrarily restricted the meaning of “necessary” to include only things both essential and convenient, he then quietly went on arguing as if he’d written “or” instead of “and.” Thus Congress’ implied powers, instead of being narrowly confined according to the Convention’s own choice of words, were so extended as to make all the fastidious language setting-forth Congress’s express powers appear otiose.

Another big step came in 1884, with Juilliard v. Greenman–the third and last of the so-called “Legal Tender Cases.” Here Chief Justice Horace Gray wrote the majority opinion, to wit, that in issuing irredeemable Greenbacks and making them legal tender Congress was merely exercising “a power universally understood to belong to sovereingty…at the time of the framing and adopting of the Constitution of the United States. The governments of Europe, ” Gray continued, “had and have as sovereign a power of issuing paper money as of stamping coin.” In short, because various, mostly monarchical, European governments assumed, among their other sovereign prerogatives, that of engaging in paper-money finance, Congress surely ought to be able to do the same. That the founders had set up a republic, based on popular sovereignty, rather than an absolute monarchy, was a detail apparently beyond either Justice Gray’s comprehension or that of the other (mostly Republican) justices who joined his majority opinion.

Although it managed to survive Juiliard v. Greenman the gold standard did not survive the Great Depression, when the Roosevelt administration, further testing the limits of the Federal government’s “implied powers,” turned Federal Reserve notes into the latest version of Congressionally-sanctioned bills of credit, confiscated all private holdings of monetary gold, reduced the dollars’ official gold content, and declared specific gold-payment provisions in both private and public contracts null and void. In all this, it almost goes without saying, the Supreme Court happily acquiesced, in a final paroxysm of monetary iniquity known as the Gold Clause decisions.

Perhaps some, reading this summary, will think, “So, the High Court overruled the founders, and got us off gold. Bully for them: had they done otherwise, those metallic ‘fetters’ of which the founders were so fond might have us still shackled tight to the very depths of the Great Slump. The founders, after all, cannot have imagined all the means now at our disposal for promoting happiness, or its pursuit. They supposed that gold and silver were the best of all possible monies; but they were mistaken.”

To such reasoning several replies seem in order. First, so far as the U.S. case is concerned, the assertion that the gold standard stood in the way of monetary expansion is wrong. As Timberlake himself points out (p. 185), at the trough of the great monetary contraction “the Fed-Treasury gold stockpile, even with all the reserve requirements in place, was still large enough to generate nearly twice as much common money–hand-to-hand currency and bank deposits subject to check–as then existed.” What’s more the Fed had the authority to relax it’s own very hefty gold reserve requirements, which included a minimum 40 percent requirement against its outstanding notes, whenever circumstances seemed to warrant doing so. In short, the collapse of the U.S. money stock was the result, not of the Fed’s commitment to maintain the gold standard, but of it’s unwillingness to part with surplus gold when doing so might have averted panic.

Second, the authors of the Constitution never pretended that they could anticipate future developments that might make some changes in the law desirable. On the contrary: it was precisely to provide for such modifications that they included Article 5, spelling-out amendment procedures. The requirements are strict; but (as experience proves) they are hardly insurmountable. And that’s just as it ought to be if the Constitution is to remain an expression of the will of the people, or at least of a majority of them.

Finally and most importantly, to apologize for the Supreme Court’s running roughshod over the Constitution’s money clauses, as so many fans of fiat money are inclined to do, is to thumb one’s nose at the rule of law itself. It is to treat constitutions and such as mere scraps of parchment, to be caste aside the moment that numbers displayed on some lightning utility calculator indicate that a new arrangement, though patently against the law, might boost social welfare.

But it’s such thinking itself that’s really mistaken: it isn’t a question of determining which arrangements might yield the greatest utility, even supposing such a calculation to have scientific merit notwithstanding the peril it poses to particular underrepresented persons, whether redheads or creditors or others, whose Hicks-Kaldor compensation checks are likely to remain forever in the mail. It is a matter of having rules that guard against arrangements which, whatever their potential advantages, have an at least equal potential to do harm. That irredeemable paper money might prove beneficial was in fact not an argument of which the founders were unaware; Ben Franklin, for one, made it in his usual, eloquent and spirited way. But the odds were then and have remained ever since against the likelihood that such paper money would be managed responsibly. Fans of the Constitution get that. It’s sad that so many of today’s calculating economists don’t.