I promise to make this my last post for a while concerning the matter of 100-percent versus fractional-reserve banking. However, in addressing some comments on my recent posts it occurred to me that some very serious misunderstanding is at play concerning the difference between a bank’s capital and its cash reserves. The distinction between these is important, because in an important sense, and particularly with respect to comparisons of fractional and 100-percent reserve institutions, the two are substitutes.

Capital serves as a cushion for the purpose of absorbing the effects of adverse shocks to a bank’s asset portfolio, so that the bank’s creditors won’t suffer losses in connection with such shocks, except in rare instances. This in turn allows the bank’s IOUs to continue to hold a fixed value in terms of the underlying reserve asset despite changes in the market value of the bank’s non-reserve assets. The larger a fractional-reserve bank’s capital cushion, the greater the adverse shocks it can handle without becoming insolvent, that is, without finding that it has run out of equity. In a free market, an insolvent bank ceases to be a going concern: it must either find a buyer or go into liquidation.

A 100-percent reserve bank hardly needs any equity capital, because the need for such capital arises only when the bank faces shocks that can reduce the value of its assets. By holding only cash reserves, such a bank eliminates most of the portfolio risks that fractional reserve banks encounter, making equity redundant. In fact past 100-percent institutions had very little if any equity capital.

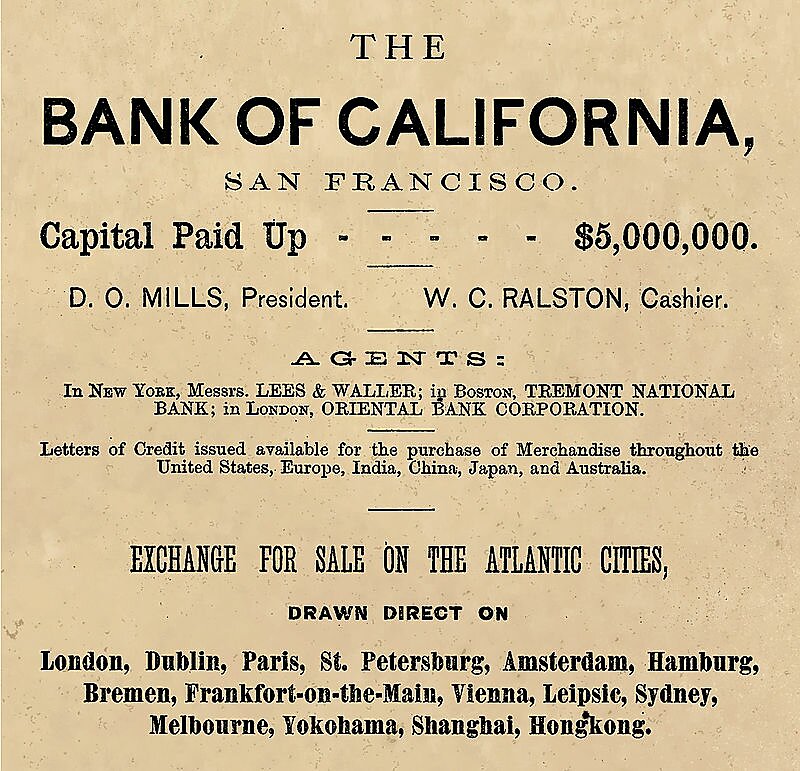

In a world without insurance, on the other hand, a risky fractional-reserve bank can only attract deposits by putting its owners’ capital at stake. Other things equal, the more capital a bank has, the more likely it will succeed in attracting risk-averse depositors. Fractional reserve banks can also attract such depositors by holding low-risk assets, such as U.S. government securities. In the past, banks used both sorts of strategies to gain market share, often taking out advertisements in newspapers in which they supplied pertinent balance-sheet details. (Although it deals only with the U.S. the best book to read about this, and how it all changed after deposit insurance was introduced, is Jim Grant’s terrific Money of the Mind.)

Of course, not all banks catered to depositors whose primary interest was safety: there was a market for riskier bank deposits also. But, despite what apologists for central banking and deposit insurance claim, it was not especially difficult to tell safer banks from less safe ones. The problem in places like the U.S. before 1934 and England before 1826 was not so much one of distinguishing relatively safe banks from relatively risky ones, but one of legal restrictions that prevented well-capitalized banks from emerging in many communities. In the U.S. the restrictions consisted of laws preventing branch banking; in England they consisted of laws preventing English banks other than the Bank of England from having more than six partners. (In 1826 other public or “joint-stock” banks were permitted, but only if they did not operate in the greater London area–itself a major limitation; while in 1833 other joint-stock banks were admitted into the London area, but only provided they gave up the right to issue banknotes.) These regulations limited the capitalization of U.S. and English banks while at the same time limiting those banks’ opportunities for financial diversification–a recipe for failure. In both instances the regulations were products of politicians’ catering to rent-seeking behavior on the part of banking industry insiders. Yet the resulting, unusual frequency of bank failures and substantial creditor losses stemming from such failures helped to sustain the belief that fractional reserve banking could only be made safe by means of further government intervention.

Where laws did not prevent banks from diversifying their balance sheets, especially by establishing widespread branch networks, or from securing large amounts of capital by “going public” (or, in the case of some Scottish and most Canadian banks, by making shareholders liable beyond the par value of their shares, which from creditors’ point of view is equivalent to having more capital), bank failures have been relatively less common, and losses to creditors stemming from occasional failures that did occur have been relatively minor. Indeed, even such a spectacular failure as that of Scotland’s Ayr Bank did not ultimately prevent the bank’s creditors from being paid in full, without need for any sort of bailout.

What has all this to do with the question of 100-percent versus fractional reserves? First of all, the 100-percenters are in the habit of posing a simple choice between “safe” 100-percent reserve banks and “unsafe” fractional reserve banks. But, even putting aside the obvious fact that banks keeping the same reserve fraction may be more-or-less safe depending on the sort of non-cash assets they hold, the comparison overlooks the role of capital in limiting the risk borne by fractional-reserve deposit and noteholders, with banks that are both well-diversified and well-capitalized being capable of exposing their creditors to very little risk even despite maintaining slim reserves. More to the point, an entire range of risk-return options may exist even for banks holding approximately equal reserve ratios. Economists are generally suspicious, and rightly so, of “corner solutions.” Yet 100-percenters have latched on to just such a solution in suggesting that it must be superior to the whole array of possible fractional-reserve alternatives.

Second, in suggesting that fractional-reserve banks exist only because their customers don’t realize that they are engaged in lending, 100-percenters beg the question: if so, why do fractional-reserve banks bother (or why did they bother, in the good-old pre-insurance days) to hold capital, and often plenty of it? As I explained above, the reason for them having done so is precisely because they needed to assure their creditors that, although their money was at risk, the risk was limited, and perhaps made very small indeed, by the bank’s capital cushion. To accumulate such capital cushions, let alone advertise them, would, of course, have made no sense at all to bankers who were determined to convince their customers that their money was all kept in a vault. On the contrary: it could only serve to give the game away.