“A progressive Christian school that offers a culturally inclusive education designed to foster creativity and collaboration and critical thinking, and also a love for Christ,” is how founder Tiffany Blassingame describes The Ferguson School. A fourth-generation educator, Tiffany taught in public and private schools for more than 20 years before creating her microschool. “My mom, my grandmother, and my great grandmother were all educators, and that’s where the name Ferguson comes from—it’s our maternal line,” she explains.

She was head of school at a private school during COVID-19, and she became frustrated seeing families who wanted to enroll there for in-person learning but couldn’t afford the tuition. “I thought, what if we created a space—I didn’t know it was called a microschool at the time—but what if we created this space where we made the overhead lower? Like multi-age classes and a much smaller space?” Tiffany recalls. “We would be limited, but it would at least cut off a lot of the overhead of running a school. Because I understood what it was to like to run a private school.”

The Ferguson School, which meets at a church, started with two students and is now at 19. The upcoming school year will be year four. Tiffany says her students are primarily from low- to middle-income families that are looking for a non-traditional environment that fosters a sense of love and belonging as they begin to navigate their identity and their identity in Christ.

The school has a K‑2 grade classroom and a 3–5 grade classroom. Families can choose between a full-time option and a hybrid option where students attend Ferguson three days a week and work at home the other two.

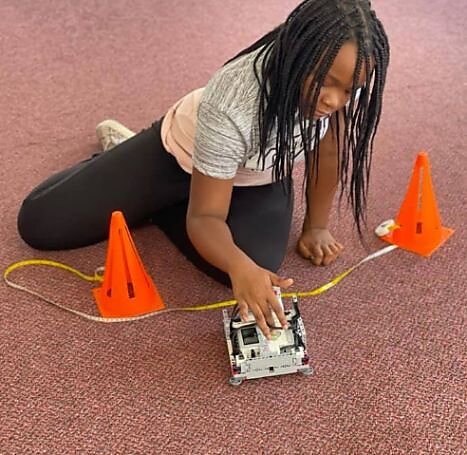

The day starts with outdoor recess and then the kids go inside for a morning activity. Tiffany says it’s usually something hands-on like Legos, clay, or a puzzle—something that is still active and collaborative but gives them a chance to calm down from recess. After a morning meeting, they move into their literacy blocks, which start with a whole group lesson around a particular topic. Then they rotate through stations, which typically include a teacher-directed station, a tech/blended learning station, and then some type of practice that’s related to the skill. After lunch, they have a STEM block that works like the literacy block but with STEM topics. Afternoon recess is held after the STEM block and then they have electives like Spanish, art, music, computer science, and library time.

Tiffany pulls from several instructional and social-emotional learning models to create a unique environment. “One of our social-emotional models, believe it or not, is the five love languages,” she says. “Our parents are learning about love languages. Our staff does yearly training on the love languages. We observe the students and figure out how they react to different ways of being shown that they are loved or that something is special.” For the older kids, they talk about the different love languages and then the students do their own self-assessment. With the younger ones, it’s primarily observation. At the first parent-teacher conference, they talk about what the parents have noticed about their children as they learn about love languages.

The students also have what Tiffany calls inclusion opportunities with a learning pod that is right across the hall from her classrooms. “We do some inclusion classes with students on the spectrum who are non-verbal,” she says. “So that’s another way the kids are able to practice showing how they care about someone and help others to feel that they are welcomed in our space. And also respect their space when we go for inclusion into their classes as well.”

Now that she’s gotten away from conventional schooling, Tiffany isn’t stopping. “The world of microschooling is challenging as far as, you know, lifestyle, finances, and those types of things,” she explains. “So I just started a microschool educator academy. It’s not for learning to start a microschool, which I see a lot of people doing. It’s for helping teachers to understand what it’s like to teach in a microschool, because it’s very different than public schools, charter schools, online environments, or traditional private schools,” she explains. The first cohort is starting at the end of July. Tiffany hopes the training allows microschool founders to step back a little and let their schools run because their teachers are so well-trained.

Tiffany realizes it’s hard to leave what you know and jump into a new environment. But she encourages both teachers and parents to give it a shot. To her fellow teachers, she says, “It’s going to be a challenge, but it’s so rewarding. You see the difference that you make.” Her message to families is similar: “Just try it. You want to be able to tell your child that you did everything you could to give them what they needed.”