One of the overlooked aspects of President Obama’s speech at West Point yesterday was his call for other countries to step forward, and do more to defend themselves and their interests. He also expected them to contribute “their fair share” in places like Syria.

It might have been overlooked because it was neither new, nor unexpected. Polls consistently show that Americans believe we use our military too frequently, and they are tired of bearing the costs of policing the planet. Meanwhile, the minority who believe that we should be spending more on the military — 28 percent of Americans, according to a recent Gallup poll – might not feel that same way if they knew how much we spend as compared to the rest of the world, especially our wealthy allies.

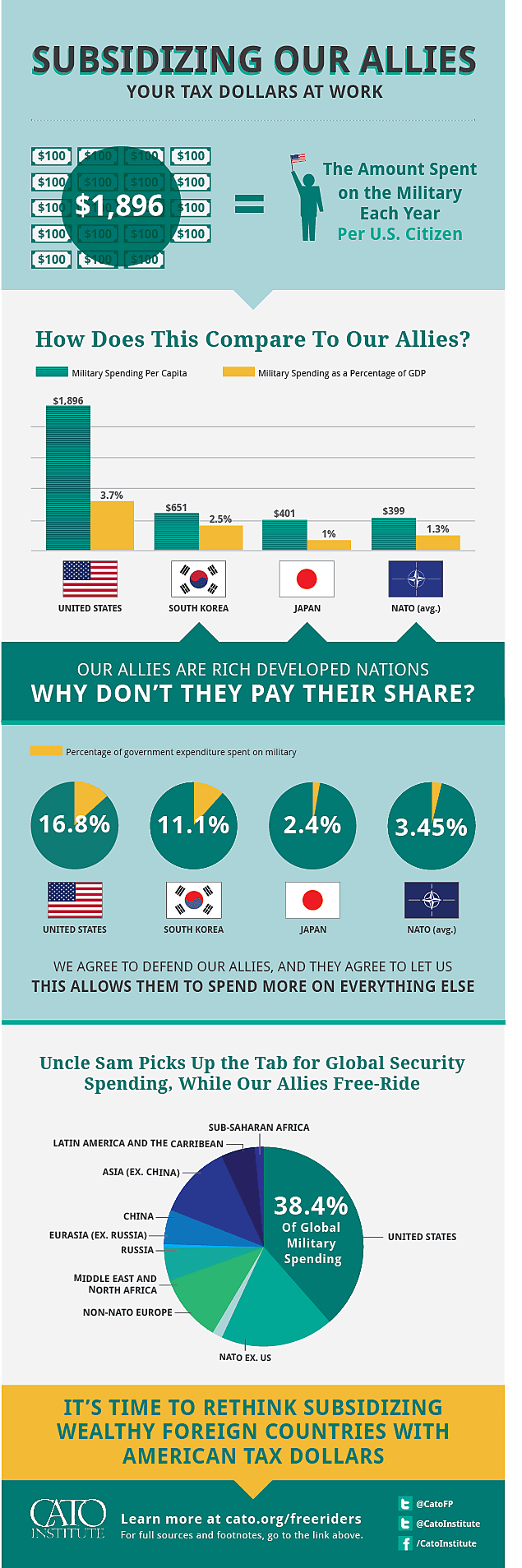

This new Cato infographic, prepared with the able assistance of my colleague Travis Evans, might help to put it all in perspective. In addition to showing how much American taxpayers spend, it also shows, indirectly at least, how that spending discourages other countries from spending more to defend themselves.

The average American spends nearly $1,900 each year on the military, based on the latest data available. In fact, Americans spend much more than that, because that figure includes the costs of the Pentagon’s base budget, as well as the costs of the wars, but excludes other national security-related expenditures in the Departments of Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security and Energy. Still, that conservative $1,896 figure is roughly four and a half times more than what the average person in other NATO countries spends on defense. These countries boast a collective GDP of approximately $19 trillion, 18 percent higher than the United States. They obviously can afford to spend more, but they don’t. The disparity between what Americans spend relative to our Asian allies is nearly as stark: South Koreans spend about a third as much, and Americans outspend people in Japan by more than four to one.

The reason why is obvious: people are disinclined to pay for things that others will buy for them. Countries are no different. Uncle Sam has picked up the tab for defending other countries since the earliest days of the Cold War, and that pattern continues to this day.

In practical terms, this means that U.S. alliances constitute a massive wealth transfer from U.S. taxpayers to bloated European welfare states and technologically-advanced Asian nations. In most of these countries, the governments who are relieved of the responsibility of defending their citizens from threats have chosen to spend their money on other things.

Consider, for example, the disparity between what the United States spends on the military as a share of total government spending, and what other countries spend. While the United States spends 16.8 percent of the budget on the military, Japan spends a paltry 2.4 percent. Our NATO allies? The average is 3.45 percent. Even South Korea’s share of military spending is only 11 percent, and they have an erratic, hostile regime on their northern border. By promising to provide for these countries’ security, and by spending hundreds of billions of dollars to back up these promises, we have encouraged them to divert resources away from defense.

The U.S. Constitution stipulates that the federal government should provide for the “common defence.” But the document never talks about providing for the defense of other nations. Some of the defenders of the current arrangement try to convince us that our allies are grateful, and that they know they would be lost without us. Just last week, for example, Secretary of State John Kerry told students at Yale, “I can tell you for certain, most of the rest of the world doesn’t lie awake at night worrying about America’s presence – they worry about what would happen in our absence.” But what our allies are really grateful for is the free ride.

We could have revisited our alliances after the end of the Cold war. We could have paid more attention to the culture of dependency we created among our allies. Instead we continued to spend vast sums on the military, discouraging others from developing their capabilities, and removing their will to use their militaries in ways that could have advanced both their and our security. Today, our wealthy allies are little more than wards of Uncle Sam’s unending dole, and they will remain militarily irrelevant so long as we continue along our present path.

Sources:

Central Intelligence Agency. “The World Factbook 2013.” Washington, D.C., 2013.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies. The Military Balance 2014. Edited by James Hackett. London: Routledge, 2014.