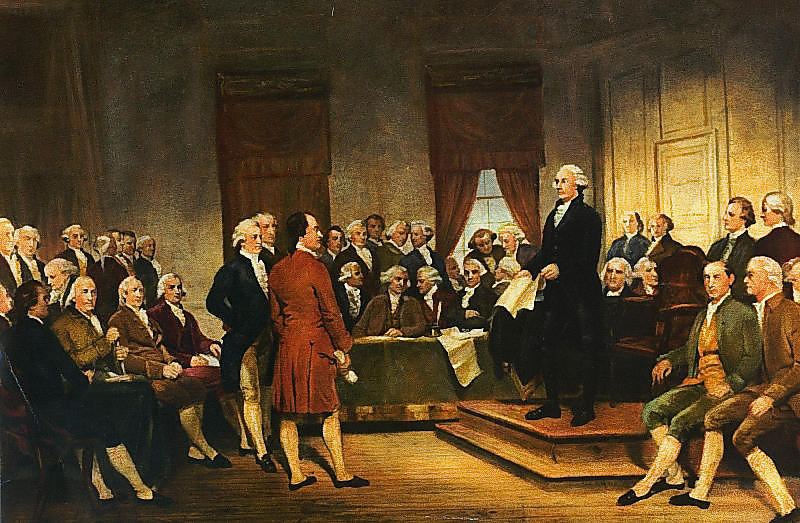

Alex Nowrasteh had an excellent post yesterday on how the western tradition on immigration and naturalization formed the basis of the Founders’ views on those subjects and resulted in the most liberal policies in the world at the time. The debates at the Constitutional Convention highlight his point, showing just how liberal the Founders had become on immigration and naturalization.

At one point, Gouverneur Morris offered an amendment that would require 14 years of citizenship, rather than four, before a person could serve as a senator, “urging the danger of admitting strangers into our public Councils.” Charles Pinckney of South Carolina seconded the motion, recalling “the jealousy of the Athenians on this subject who made it death for any stranger to intrude his voice into their legislative proceedings.”

Yet as Alex notes, the Romans—rather than the Greeks—informed the views of most founders on naturalization, and most of the representatives at the convention opposed the Morris amendment for fear of, as future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Oliver Ellsworth put it, “discouraging meritorious aliens from emigrating to this Country.” Alexander Hamilton argued that the “advantage of encouraging foreigners was obvious and admitted,” asserting that “persons in Europe of moderate fortunes will be fond of coming here where they will be on a level with the first Citizens.”

Father of the Constitution James Madison “was not averse to some restrictions on this subject, but could never agree to the proposed amendment” in part “because it will discourage the most desirable class of people from emigrating to the U.S.” In other words, not only were the Founders opposed to restricting the free movement of people into the United States, but they opposed restrictions on citizenship that they felt would discourage immigrants from using that freedom. Madison spoke of “great numbers” who would wish to come to the United States.

The goal of a “liberal” Constitution was one that the representatives repeated often (if not always pursued). In a separate conversation on the issue of qualifications to serve in office, Benjamin Franklin noted that the “Constitution will be much read and attended to in Europe, and if it should betray a great partiality to the rich, it will not only hurt us in the esteem of the most liberal and enlightened men there, but discourage the common people from removing to this Country.” On this amendment, he made the same point, stating he “was not against a reasonable time, but should be very sorry to see anything like illiberality inserted in the Constitution.”

Madison agreed, further arguing that the amendment “will give a tincture of illiberality to the Constitution.” Edmund Randolph of Virginia “reminded the Convention of the language held by our patriots during the Revolution, and the principles laid down in all our American Constitutions.”

James Wilson of Pennsylvania, who helped produce the first draft of the Constitution, was himself an immigrant from Scotland and raised the possibility of himself “being incapacitated from holding a place under the very Constitution which he had shared in the trust of making.” He noted that two other representatives—Robert Morris, originally of England, and Thomas Fitzsimons, originally of Ireland—shared the same situation. Furthermore, Wilson described “the discouragement & mortification [immigrants] must feel from the degrading discrimination now proposed,” noting that he had himself “experienced this mortification.” He said it “was wrong to deprive the government of the talents virtue and abilities of such foreigners as might chose to remove to this country.”

Madison and Franklin argued against the anti-immigrant conspiracy theories of the day that held that foreign governments would leverage their expatriates to their advantage. Franklin noted, “When foreigners after looking about for some other Country in which they can obtain more happiness, give a preference to ours, it is a proof of attachment which ought to excite our confidence and affection.” Madison added that foreign governments’ “bribes would be expended on men whose circumstances would rather stifle than excite jealousy and watchfulness in the public.”

Even those who favored a longer restriction on citizenship made clear that it was by no means out of opposition to immigration. George Mason of Virginia stated that he was “for opening a wide door for emigrants.” Moreover, he opposed an outright ban on naturalized citizens serving in the Senate in light of those foreigners who supported the cause of independence. Even Gouverneur Morris “ran over the privileges which emigrants would enjoy among us, though they should be deprived of that of being eligible to the great offices of Government; observing that they exceeded the privileges allowed to foreigners in any part of the world.”

Morris lost the vote 7 to 4, but the convention did adopt a higher standard of nine years on a second vote of 6 to 4. Yet despite this, their statements make clear that the Founding Fathers had a conception of citizenship and immigration that shares little in common with today’s nationalists. They wanted the most open possible society where foreigners could aspire to full citizenship in a reasonable time frame and receive equal treatment to citizens as soon as possible.