The American presidency has accumulated an unprecedented set of institutional advantages in the conduct of foreign policy. Unlike on the domestic side where presidents face an activist and troublesome Congress, the Constitution, the bureaucratic and legal legacies of previous wars, the overreaction to 9/11, and years of assiduous executive branch privilege-claiming now afford the White House great latitude to run foreign policy without interference from Congress.

But one of the most tragic reasons for this situation stems from the abject failure of the marketplace of ideas to check the growth in executive power. In theory, the marketplace of ideas consists of free-wheeling debate over the ends and means of foreign policy and critical analysis of the ongoing execution of foreign policy that help the public and its political leaders to distinguish good ideas from poor ones. Philosophers since Immanuel Kant and John Stuart Mill have championed this dynamic. The Founding Fathers enshrined its logic in the First Amendment. Recent scholarship argues that the marketplace of ideas is central to the democratic peace and the ability of democracies to conduct smarter foreign policies than other nations.

In practice, however, today’s marketplace of ideas falls terribly short of this ideal.

The most famous recent example is the run up to the 2003 Iraq War. The Bush administration used an assortment of half-baked intelligence, exaggerations, and flat out lies about Iraqi WMD programs to urge the public into supporting the war. Shockingly, however, the national debate over the war was muted. Though false and based on flimsy evidence, the Bush administration’s claims received surprisingly little criticism. Reality reasserted itself, of course, as the failure to find any evidence of such programs made it clear that the administration had waged war under false pretenses. Where was the vaunted marketplace of ideas?

In an influential article in International Security written just after the 2003 Iraq War, political scientist Chaim Kaufmann argued that a good deal of the reason for the Bush administration’s ability to sell the war lay in the president’s institutional advantages. As president and Commander in Chief, Bush not only controlled the flow of critical intelligence information, he also enjoyed greater authority in the debate than his critics, allowing him to (falsely) frame the operation as part of the war on terrorism, thus taking advantage of the public’s outrage over the 9/11 attacks.

But Kaufmann (among many others) made another argument about why Bush succeeded: the news media simply failed to do its job. Indeed, after a review of its coverage of the run up to war, the New York Times editorial board took the unusual step of acknowledging it had failed in its core mission: “Looking back, we wish we had been more aggressive in re-examining the claims [about Iraqi WMD] as new evidence emerged — or failed to emerge.”

At this point, one might assume that more than a decade of intervention, chaos, and terrorism in the Middle East would have provided the news media with a powerful set of lessons. These lessons might include things like: scrutinize the basis for intervention; ask hard questions about the plans for what happens after the initial military operation ends, work to appreciate how U.S. actions affect the attitudes and actions of other people, groups, and nations around the world.

Unfortunately it does not appear that the news media has learned much if anything. President Obama has spent eight years talking about withdrawing the United States from the Middle East but has in fact expanded the military footprint of the United States. He has done so without much real debate in the mainstream news about the wisdom of his actions. Tellingly, what debate has occurred has focused on erroneous claims that Obama has appeased our enemies by withdrawing too much.

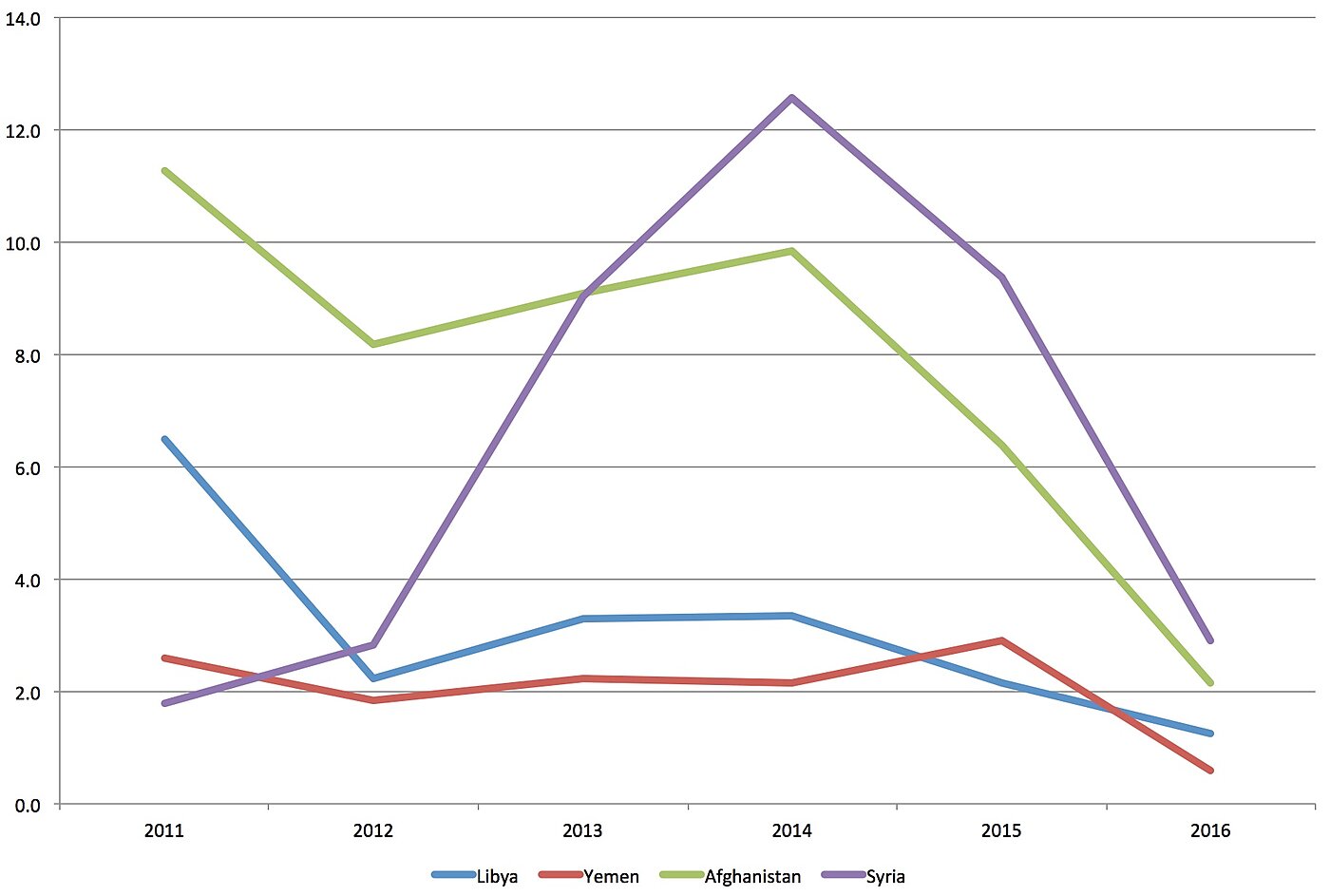

The figure below reveals some telling evidence of this sad state of affairs. Libya, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Syria all represent countries in which the United States is engaged in combat in various ways and at varying levels of intensity. Crucially, each represents a situation with the potential to involve the United States military in a bigger and messier conflict.

Figure 1. Stories per Newspaper per Month Mentioning Obama & U.S. Military & Country Name

Source: New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal via Factiva

The figure indicates how often each month the three most important newspapers in the country (the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal) mention President Obama, the U.S. military, and the name of the country in the same story. In each case the newspapers are writing fewer stories per month in 2016 than they did in 2015 and the numbers over all are quite low. The average reader of one of these newspapers would have read just three stories about U.S. military involvement with Yemen, for example, assuming he or she was diligent enough to have caught all three stories over the past four and half months.

This is no doubt an imperfect measure of the national debate about Obama’s foreign policy; it certainly fails to capture some of the other sources of information and debate. That said, it is difficult to imagine that the marketplace of ideas could be very robust without a good number of such stories in the mainstream news media. Moreover, this is something of a best-case metric for the marketplace since this figure only includes data from three newspapers that cover foreign affairs far more intensively than almost all other American news outlets.

For those who were hopeful that the American marketplace of ideas on foreign policy would improve as 9/11 receded into history, this comes as bad news. It suggests that the challenges to free-wheeling debate do not lie simply in emotional overreactions to terrorism, or to temporary Congressional obsequiousness to the White House. Recent concerns about presidential foreign policy narratives aside, it also suggests that the problem isn’t simply political spin. The problem is deeper than that. At root is a failure of the marketplace of ideas in at least one if not both of its most fundamental elements. The first possibility is that the news media in its current form – dominated by big corporations and yet weakened economically by the Internet, audience fragmentation, and increasing partisanship – is incapable of doing the job the marketplace of ideas requires of it. The second, even darker possibility, is that the public, the ultimate arbiter of what the news must look like, is simply uninterested in having the necessary debate required to force the White House to be honest and transparent about foreign policy.