A couple of weeks ago I discussed a New York Times report on soaring food stamp use. Yesterday, the New York Times reported that cash welfare use in New York under the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program started to rise more recently. The Times calls this “something of a riddle” given that food stamp usage has been increasing throughout the recession.

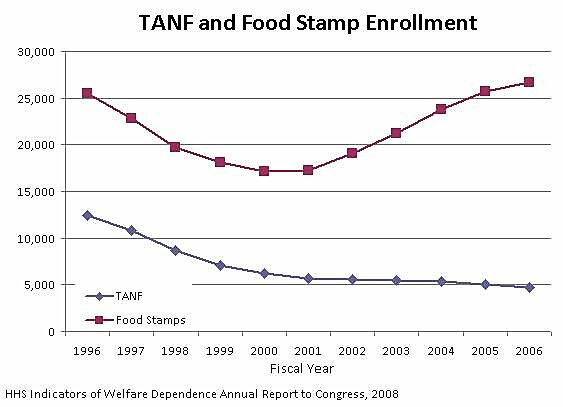

But the Times solves the riddle when it acknowledges: “It is much simpler to receive food stamps than cash assistance.” The 1996 welfare reform that replaced the broken Aid for Families with Dependent Children with TANF imposed more stringent time limits and work requirements on recipients. By contrast, the 2002 farm bill expanded food stamp eligibility, increased benefits, and made it easier to claim benefits. The following chart shows the result:

A food stamp user interviewed by the Times explains:

“It used to be easier to go on cash assistance,” she said as she left a food stamp office in Brooklyn this month. “You didn’t have to go to work, you didn’t have to report every day to an office and sign in and sign out. Now, if you don’t go to those group job meetings in the mornings, they shut down your whole welfare case. So that’s why I just get food stamps.”

In the Times article on food stamps, the USDA official in charge of the program was reportedly happy that usage was up and even wanted to see continued growth. The new article quotes an advocate for government welfare programs with similar feelings on cash welfare:

“It should be considered a positive thing and a natural thing as we start to head into a 10 percent overall unemployment rate in New York,” said David R. Jones, the president and chief executive of the Community Service Society, one of the city’s oldest social services agencies for low-income people. “If unemployment rates continue to spiral upward in New York, and you didn’t see an increase in welfare, something would be seriously wrong. That would mean that we weren’t getting people on relief quickly enough.”

The Community Service Society’s website says its mission “is to identify problems which create a permanent poverty class in New York City, and to advocate the systemic changes required to eliminate such problems.” But the federal welfare system has created a permanent poverty class.

Michael Tanner got it right in his book, The Poverty of Welfare, that government officials and welfare activists have a vested interest in these programs:

Whatever the intention behind government programs, they are soon captured by special interests. The nature of government is such that programs are almost always implemented in a way to benefit those with a vested interest in them rather than to actually achieve the programs’ stated goals. Among the non-poor with a vital interest in anti-poverty programs are social workers and government employees who administer the programs. Thus, anti-poverty programs are usually more concerned with protecting the prerogatives of the bureaucracy than with fighting poverty.