With Congress still considering a $50 billion-plus subsidy package for U.S. semiconductor manufacturing, I’ve discussed the many (many) reasons why such subsidies are costly and unnecessary, as well as the ignominious history of similar industrial policies in the United States. This doesn’t mean, however, that the U.S. government should simply do nothing. Instead, there are many horizontal, pro-market policy reforms that would deliver substantial benefits to chipmakers and other capital-intensive advanced manufacturers in the United States while avoiding U.S. industrial policy’s common pitfalls – picking losers, politicization, economic costs (seen and unseen), etc. Here are my Top 5:

- Expand immigration

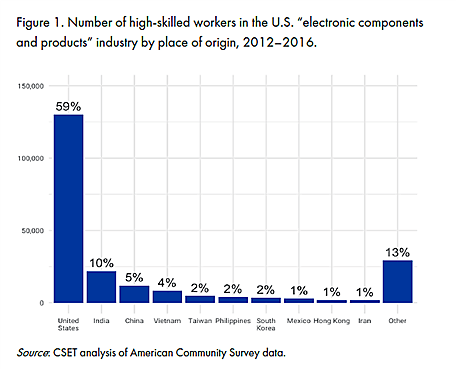

As Cato scholars have frequently explained, educated immigrants boost U.S. innovation and productivity and disproportionately benefit the U.S. semiconductor industry and related ecosystem. Approximately 40 percent of high-skilled semiconductor workers in the United States were born abroad (most come from India and China), and 87 percent of semiconductor patents awarded to top U.S. universities in 2011 had at least one foreign-born investor. International students comprise two-thirds of graduate students in the top fields feeding into the U.S. semiconductor industry, and roughly 80 percent of international PhD graduates in these fields stay in the country after finishing their degrees (stay rates are at around 90 percent for Chinese and Indian PhD graduates).

Surely, improving the U.S. educational system should also be a priority, but the benefits of any such reforms will take years to materialize. Thus, expanding high-skilled immigration will continue to be necessary for the U.S. semiconductor industry to flourish in the future, something the Biden and Trump administrations have recognized:

Furthermore, human capital continues to be one of the United States’ biggest advantages over China, whose chip industry has struggled to retain talent, and research shows that past U.S. restrictions on high-skilled immigration pushed R&D activities offshore (including to China) and decreased U.S. innovation and output. Expanding immigration is thus an economic and geopolitical no-brainer for the country as a whole, with major benefits for U.S.-based chipmakers too.

2. Improve tax treatment of capital investments

A recent report by the Tax Foundation shows that the U.S. tax system is biased against capital intensive manufacturers, including chipmakers (whose massive facilities – “fabs” – cost billions of dollars). Whereas most business costs can be immediately deducted in the year they are incurred, deductions for costs associated with physical capital must be spread out across multiple years (known as “recovery periods”), leading to a decline in the real value of these deductions due to inflation and the time value of money:

“Recovery periods” vary across asset classes and are the worst (longest) for commercial structures like fabs. Forcing chipmakers to spread out their deductions over long periods of time raises the cost of making such capital investments (especially in periods of high inflation). Because of this, “any policy stopping short of full, immediate expensing for capital investment places heavy industry at a disadvantage” versus services because “physical assets like machinery and structures make up a larger share of the expenses” of the former group (which includes semiconductor manufacturing). The authors thus conclude that “[r]ather than offer wasteful, poorly-timed subsidies to [a chip] industry already making investments in the United States, lawmakers could stimulate investment by ending the tax penalties against it.”

3. Remove tariffs

Tariffs also raise U.S. chipmakers’ costs and deter domestic investment. The U.S. Semiconductor Industry Association, for example, has sought exclusions from President Trump’s “Section 301” tariffs on Chinese imports because they apply to certain products that American manufacturers need but are in “critically short supply.” According to the group, “[i]mposing a 25% tariff on imports of the parts and components that go into U.S.-made semiconductor manufacturing equipment and other products in the semiconductor supply chain would substantially increase the cost of semiconductor manufacturing in the United States, and therefore disincentivize investments in U.S. manufacturing” – an outcome that’s “directly counter to the bipartisan Administration and Congressional goal of urgently expanding U.S. semiconductor manufacturing.” President Biden could remove these tariffs with the stroke of a pen.

U.S. “trade remedy” (antidumping and countervailing duty) taxes add insult to chipmakers’ injury. These import duties apply to not only materials used to produce semiconductors, such as glycine from China, India, and Japan, but also a wide array of imported construction inputs, which have been found to significantly increase domestic prices. A common claim from semiconductor subsidy enthusiasts is that government funds are needed because it’s so much costlier to build a fab in the United States than in Asia. Reforming the U.S. system that allows for these and other duties to be applied without regard for their consumer or broader economic harms could help level the playing field.

4. Pursue trade agreements

New U.S. trade agreements are another obvious move that would help the U.S. semiconductor industry. For example, the U.S. government could expand the National Technology and Industrial Base to include allies like Japan, South Korea, Germany and the Netherlands, which are dominant in certain stages of the semiconductor supply chain. The NTIB currently covers only Canada, Australia, and the UK and liberalizes defense-related trade, investment, and R&D collaboration among member countries. Adding other allies would, for example, exempt them from U.S. investment screening and relax U.S. export controls on semiconductors and their inputs, thus benefiting the American industry.

More comprehensive U.S. trade agreements, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Partnership (formerly the TPP) and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with the EU, would expand access to imported semiconductor-related goods and services and would lower foreign barriers to U.S. semiconductors and high-tech devices. The United States is already a top-five global exporter of semiconductors and related equipment, and providing additional opportunities for export would raise the revenues of, and encourage greater investment in, the domestic industry. Eliminating barriers to cross-border data flows, moreover, could boost both the data-driven stages of semiconductor production and commercial activity by semiconductor-users in the United States and abroad (thus increasing demand for chips). It’s thus no surprise that the SIA was a vocal supporter of the TPP and has called on the U.S. government to join the CPTPP (along with Taiwan and South Korea).

5. Reform export controls

Finally, U.S. policymakers should follow my Cato colleague Clark Packard’s recent advice and reform the U.S. export controls regime by limiting restrictions to real national security threats; omitting goods that are available in other countries; streamlining export licensing processes; and ensuring flexibility through sunset provisions or mandatory annual reviews. Export controls (such as the ones imposed by the Trump administration on chips and chipmaking equipment sold to China) can have legitimate national security aims, but they also can harm American companies and discourage investment in covered industries (while encouraging investment abroad).

Semiconductor export controls have been tightened in recent years to prevent China from getting access to U.S. technology. Yet China represents an important market for U.S. semiconductor companies, and, as a Boston Consulting Group report indicates, U.S. companies could lose more from maintaining or tightening current export controls than they would from Chinese industrial policy. Unilateral export controls, moreover, are unlikely to prevent China from accessing covered technologies and could have serious unintended consequences. Georgetown’s Abraham Newman points out, for example, that the Trump administration’s “effort to limit Chinese advances in semiconductors” (via restrictions on exports to China’s largest chipmaker SMIC) “took a major producer of semiconductors basically offline as companies avoided using their product” (thus reducing global supply) and caused companies to “hoard chips to evade U.S. sanctions” (thus increasing demand). None of this is good for the U.S. semiconductor industry.

***

The Biden administration and its allies in Congress have, thus far, opted to embrace subsidies as the primary means for boosting the productive capacity of the U.S. semiconductor industry. But what these companies really need is access to global markets and talent, as well as a business environment that makes it easy to mobilize resources and upscale production in response to ever-changing global dynamics. The policies above might not produce a nice ribbon-cutting photo op for the folks in Washington, but they would – unlike industrial policy – help to achieve their stated semiconductor objectives.