As I was preparing for a Demand Progress-sponsored panel on Congressional oversight of intelligence matters on the afternoon of February 9, Demand Progress Policy Director Daniel Schuman and I agreed that if President Trump was going to refuse to “declassify” the House Intelligence Committee Democrats rebuttal to the “Nunes Memo,” he would wait until the late Friday news cycle to do it. We didn’t have to wait long for that prediction to come true.

In a moment, I’ll get to the issue of whether Trump actually has the authority under the Constitution to do what he did, but I want to start with is this paragraph from the New York Times story referenced above:

But Donald F. McGahn II, the president’s lawyer, said in a letter to the committee on Friday night that the Democratic memo could not be released because it “contains numerous properly classified and especially sensitive passages.” He said the president would again consider making the memo public if the committee, which had approved its release on Monday, revised it to “mitigate the risks.”

In that same NYT story, House Intelligence Committee ranking member Adam Schiff provided further context:

In a statement on Friday night, Mr. Schiff said that Democrats had provided their memo to the F.B.I. and the Justice Department for vetting before it was approved for release by the committee. The Democratic memo was drawn from the same underlying documents as the Republican one.

“We will be reviewing the recommended redactions from D.O.J. and F.B.I., which these agencies shared with the White House,” Mr. Schiff said, “and look forward to conferring with the agencies to determine how we can properly inform the American people about the misleading attack on law enforcement by the G.O.P. and address any concerns over sources and methods.”

So if Schiff is to be believed, House Intelligence Committee Democrats ran their memo by Justice Department and FBI officials prior to the unanimous committee vote to release his memo, then sent the memo over to the White House for reaction. Trump and his team then demanded still more redactions. If the above account is correct, the same Justice Department or FBI officials who reviewed the original “Schiff Memo” apparently demanded still more redactions once it got to Trump’s desk.

It’s this sequence of events which brings me to the question of whether Trump has the authority under the Constitution to censor or rewrite Congressional work product, with or without Congressional assent, if it contains references to Executive branch information asserted as being classified, in part or in whole. The short answer is no. The longer answer is still no, but with some caveats.

Congress and Secrecy

The word “secrecy” appears only once in the Constitution, specifically in Article I, Section 5, which contains the following clause:

Each House shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such Parts as may in their Judgment require Secrecy; and the Yeas and Nays of the Members of either House on any question shall, at the Desire of one fifth of those Present, be entered on the Journal.

From the beginning of the Continental Congress in 1774 through the adoption of the Constitution in 1789, the Congress was responsible for keeping such matters of state secret as they deemed necessary. It was not until 1818 that Congress passed a resolution directing President Monroe to publish previously secret material from the nation’s earliest history.

The ability of the Executive branch to keep military and foreign policy secrets was not something Congress would get involved in legislating until well into the 20th century. Examples include the Atomic Energy Act, the Freedom of Information Act, and the Classified Information Procedures Act.

It’s worth noting that in none of these statutes did Congress renounce its authority to make materials covered by these laws public if it chose to do so—including material deemed classified by the Executive branch. The first real confrontation over this principle occurred in the aftermath of Congressional investigations of Executive branch domestic spying scandals that first surfaced in 1971.

The Pike and Church Committees

In 1975, the House and Senate each created Select Committees to investigate domestic spying and political repression operations carried out by the NSA, FBI, CIA, and military intelligence elements. The two committees became known by the names of their respective chairmen: Frank Church (D‑ID) in the Senate and Otis Pike (D‑NY) in the House. Both committees encountered deliberate efforts by Ford administration officials to block access to relevant agency or department records, resulting in months of often heated confrontations with CIA, NSA, FBI, and White House officials over committee demands for documents.

As I noted in a recent piece in The Hill, the slightly differing approaches of the two committees led to very different outcomes:

In a now-infamous incident known as the “September compromise,” Pike agreed to allow the Ford administration to make the call about what executive branch documents could or could not be made public. When Pike moved to finalize his committee’s report and make it public in January 1976, Ford persuaded the House to block publication on the grounds that the entire Pike Committee report was a classified document. In contrast, the Senate refused to submit the Church Committee report for Ford’s review and published its findings in April 1976. Constitutionally, Church and his colleagues made the right call, Pike’s House colleagues the wrong one.

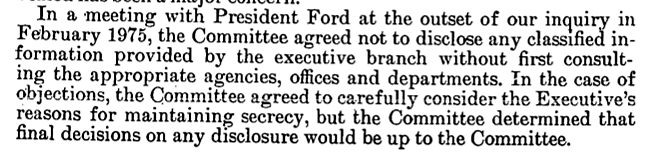

Indeed, in its preamble to its final report, the Church Committee made its position abundantly clear (from the committee’s final report, Vol. 1, p. 13):

It should be noted that the Ford administration made no attempt to challenge the Church Committee’s publication of the report in federal court—a de facto admission that the Congress did indeed have the authority to release—and thus simultaneously declassify—information previously deemed secret by Ford and his predecessors.

The Caveats

The Pike Committee experience proved that the Executive branch could, under the right circumstances, still thwart an official Congressional release of information President Ford and his agency heads considered classified. However, he needed help to do it—in this case, Pike’s House colleagues, who failed to authorize the release of the Pike Committee report.

The subsequent legislation passed by the House and Senate creating standing Select Intelligence Committee’s largely adopted the system that had been used by the House in the Pike Committee episode. Molly Reynolds of Brookings recently wrote a good overview of this process at Lawfare.

What the “War of the Memos” reveals is that the original Church Committee approach to this kind of Executive-Legislative confrontation was the right one. The process now being used—and more than likely abused—by the House Intelligence Committee GOP majority and the Trump White House makes it far less likely that the public will learn the truth about whether or not the FBI and Justice Department misled the FISA Court in the Carter Page episode. The larger and more long-term ramifications of this episode are that a new and dangerous precedent is being set by not just the House Intelligence Committee, but the Congress as a whole.

Letting any President dictate what Congress can or cannot publish is a clear assault on the Separation of Powers. It’s also possible for Congress to voluntarily breach the Separation of Powers and compromise its oversight of intelligence matters. That was the error committed by Senator Diane Feinstein (D‑CA) when she voluntarily submitted the Senate Intelligence Committee’s full report on the Bush 43-era CIA torture program to President Obama for a “declassification” review. Instead, Obama—a fellow Democrat—sat on the full committee report. To date, Feinstein has failed to get her Senate colleagues to hold a vote to make the full report public.

Trump’s quashing (at least for now) of the “Schiff Memo” only underscores why the House and Senate must modify their respective chamber rules to make it clear, as the Church Committee did, that while the House and Senate Intelligence Committees will consider Executive branch concerns and arguments against making something public (and thus declassifying it), the final call will remain with the committees.