President Trump created a stir by dismissing as “too complicated” the border adjustability feature in the House Republican corporate tax reform. Yet a few days later his press secretary Sean Spicer suggested the seemingly rejected border tax could pay for a Mexican border wall.

Meanwhile, the President suggested the dollar is “too strong” even though (1) Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross boasted about Trump having talking the Mexico peso down 35% and (2) Martin Feldstein and other economists pushing border adjustability predict that the plan would push the dollar 25% higher.

To call border adjustability too complicated is starting to look like a huge understatement.

In the House Republicans’ tentative “Better Way” plan, border adjustment means corporations could no longer treat expenses of imported materials, parts, or equipment as a cost doing business. Manufacturers of electrical machinery or plumbing parts could not deduct the cost of copper (36% of which is imported). Retailers could not deduct the cost of imported goods. Refiners would pay a 20% tax on crude oil from Canada.

Exports, by contrast, would not count as income for U.S. tax purposes. Big exporters might even qualify for a federal check. “Any border adjustment should include cash refunds for exporters,” writes economist Alan Viard.

This “border adjustability” is said to be comparable to the way we exempt foreigners from our sales and excise taxes and other countries likewise exempt us from their equivalent value added taxes (VAT). But that analogy depends on treating a tax on corporate cash flow (essentially income minus expensed investments) as equivalent to a tax on sales. I plan to discuss the VAT analogy in a separate blog.

Tax Policy Center economist Bill Gale notes, “Many economists—but very few non-economists—believe that the international trade effects of border adjustments will be small.” Indeed, the architects of the House GOP plan, as well as potential winners and losers among business leaders, depict the House GOP tax proposal as an export incentive and import penalty. So does economist Diana Furchtgott-Roth who writes, “Border adjustability taxes are essentially tariffs under another name.” Carolyn Freund of the Peterson Institute likewise shows how a “Maryland-produced sweatshirt will face a lower tax rate than the Chinese-produced sweatshirt, exactly as if a tariff were applied.” Foreign trading partners will surely see it the same way.

How can economists disagree? “In a simple textbook model,” explains Alan Viard, “a border adjustment would trigger a real increase in the value of the dollar that would raise the cost of U.S. exports and reduce the cost of U.S. imports by an amount that would exactly offset the direct effects of the border adjustment.”

This textbook model claims the so-called “destination-based cash-flow tax (DBCFT)” will not affect the U.S. trade deficit because, as Paul Krugman explains, “wages and/or the exchange rate would change.” Rather than dealing with changing wages, border adjustment enthusiasts claim the real exchange rate of the dollar would supposedly rise “exactly” enough to make U.S. exports sufficiently expensive to foreigners to “exactly” offset the export subsidy. And the dollar prices of foreign imports would likewise fall by “exactly” the right amount to compensate for the importers’ extra 20% tax, neither more nor less.

“If the dollar doesn’t rise quickly enough or high enough,” notes The Wall Street Journal, “a border-adjusted tax is expected to penalize big retailers and other large corporations reliant on lower-cost foreign production.” Even if we could be certain of the real exchange rate rising by 25%, past experience does not suggest that is likely to happen in fewer than four years, or that import prices would fall proportionately or uniformly.

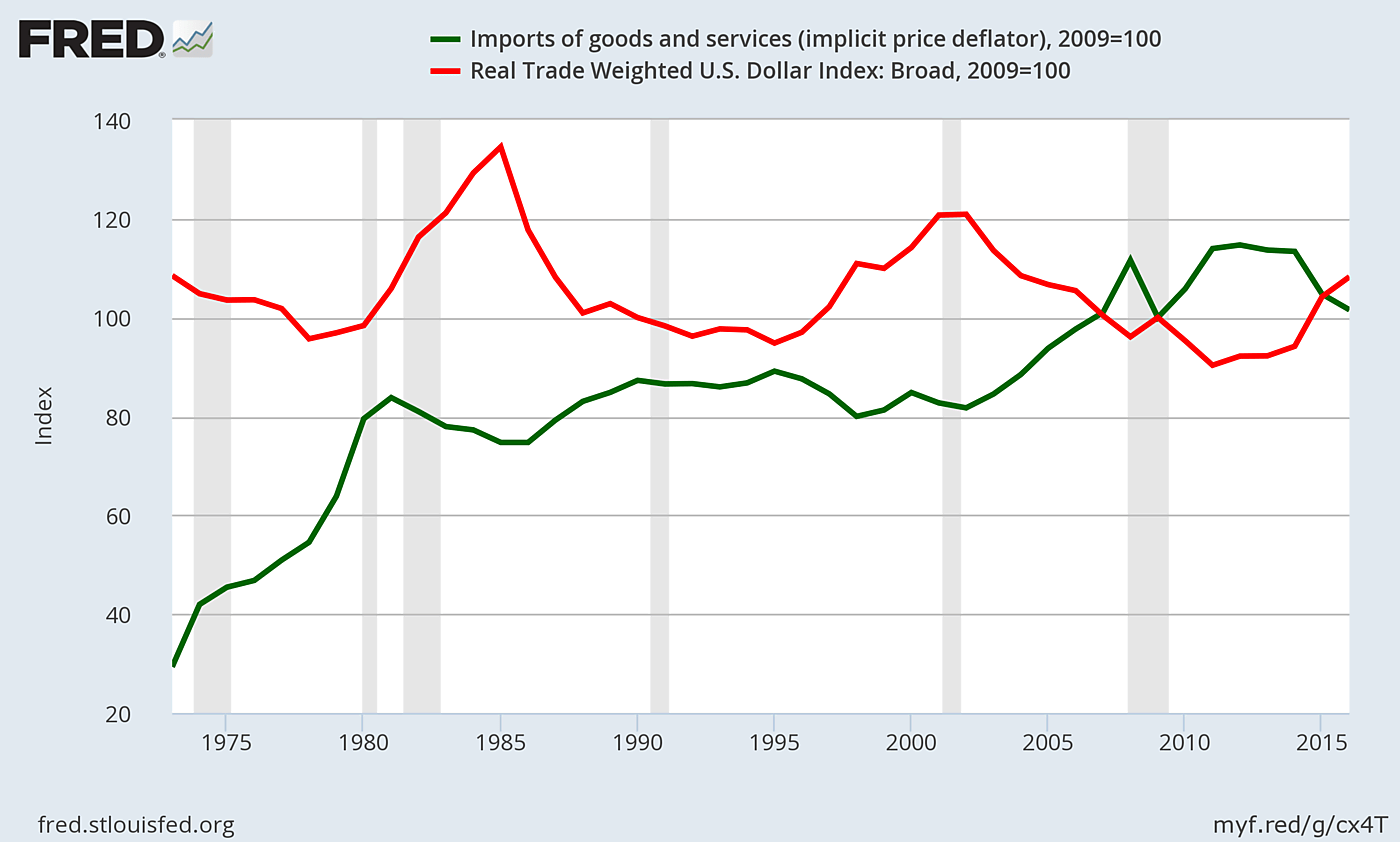

As the graph shows, the broad trade-weighted measure of the dollar’s real exchange rate rose 27.5% from 1995 to 2002, but the GDP deflator for import prices fell just 8.3%.

Be careful what you wish for. As Krugman notes, “there might be a lot of short-to-medium financial consequences from a stronger dollar.” Indeed.

Recall 1981–85, when the real dollar also rose 27.1% from 1981 to 1985 and the GDP deflator for import prices also fell more modestly, by 12.1%. Deflation of dollar-based commodity prices proved so devastating to dollar-indebted LDCs that five major central banks made a concerted effort to push the dollar back down between the Plaza Accord of September 1985 and the Louvre Accord of February 1987.

Those who predict a border adjustable corporate tax will be exactly neutralized by exactly perfect changes in exchange rates and import prices seem to be saying it would have no effect on trade. That can’t be right. If it had no effect on trade, then it would have no effect on exchange rates. After all, the reason the dollar is assumed to rise is because (1) subsidizing exports will make foreigners demand more dollars to buy more U.S. exports, and (2) taxing imports will make dollars more scarce by shrinking U.S. imports. To argue that trade will not be affected in the long run, theorists must first agree that the balance of trade will indeed be greatly distorted in some undefined short or medium run.

“Border adjustments do not distort trade,” write Alan Auerbach and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, “as exchange rates should react immediately to offset the initial impact of these adjustments.”

Unfortunately, what “should” happen in a simple textbook model is not a plausible prediction of what will happen—immediately or otherwise. The tax-induced drop in imports would happen immediately, but any resulting change in exchange rates and prices would happen later.

How much later? Nobody says because nobody knows.

Any economist who asserts a predictable and tight connection between exchange rates and all import prices is substituting theory for facts. And any economist who could predict exchange rates would quickly become a billionaire by betting on foreign exchange futures.

The “Better Way” plan would allow firms to write-off the cost of new capital equipment immediately, but corporations would no longer be able to deduct interest expense. Firms with big debts are not necessarily the same firms with big capital investments, so this alone builds potential political conflict among interest groups supporting or opposing reform. Expensing and disallowing interest deductibility will be tricky bridges to negotiate. Trying to add border adjustability for direct taxes would be a bridge too far.

The corporate tax needs to be reduced more than it needs to be “reformed.” Holding a lower corporate tax rate hostage to complicated and divisive border adjustments could easily make it impossible for an overly-ambitious House GOP tax package to win the approval of business leaders, foreign trading partners or the U.S. Senate.