Federal Reserve officials spent months talking-up their visions of a linear upward path for the overnight federal funds rate on bank reserves, but with few clues about when the increase might stop or why.

But markets do not wait for the Fed to act. The policy-making Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had done nothing until now except to raise the fed funds rate a quarter point in March. Yet they nonetheless managed to double mortgage interest rates and crash the value of bonds and stocks in retirement accounts by simply talking increasingly boldly about what FOMC members “project” might happen to the fed funds rate in the future.

There was little to learn from today’s unsurprising half-point increase in the fed funds rate and a year-late start at undoing the QE bond-buying spree. That and much more was already fully capitalized in the huge fall in bond prices and rise in their yields.

What matters is not what happened today but what happens next. Future interest rates and prices are deeply dependent on global markets. Future interest rates will not necessarily do what Fed officials predict or want but will instead change with this unruly world.

Global bond traders were typically quick to liquidate long-term investments as FOMC projections and statements pointed to faster and longer increases in short-term rate. Yet investors have strong incentives to look at much more information than just Federal Reserve officials’ diverse and variable statements. That may explain why the yield on 2‑year Treasury bonds is a much quicker and more accurate predictor of the fed funds rate than the periodic “projections” of the Federal Open Market Committee.

A rising fed funds rate is always followed by falling fed funds rate, eventually. When the fed funds rate is reduced before a recession begins, we call that a “soft landing.”

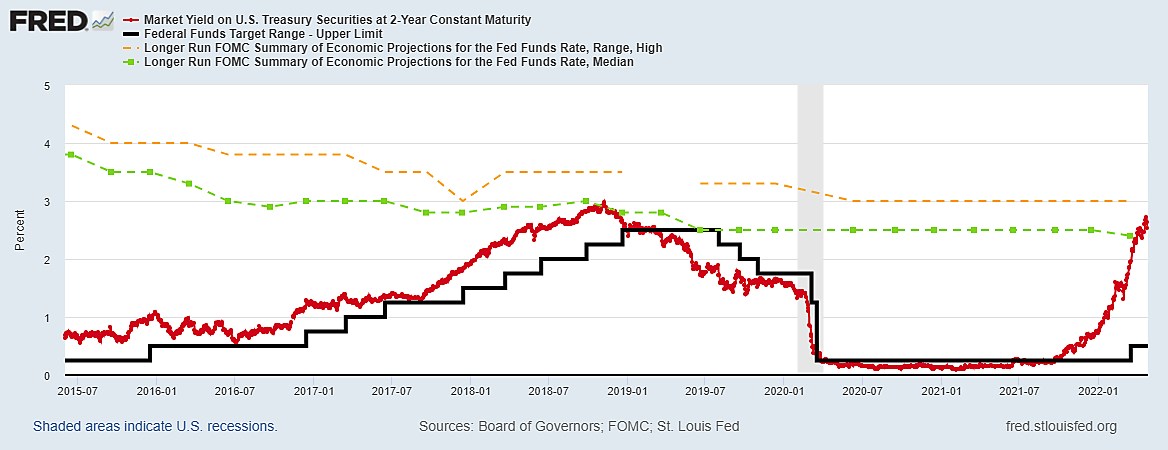

A rare soft landing occurred in 2018–19, but it was not the result of brilliant planning by the FOMC. What the Fed planned to do was to keep raising the fed funds rate to 3–4%. But investors in 2‑year bonds bet that would not be sustainable. As the 2‑year yield began to fall below the fed funds rate the yield curve inverted and the Fed reacted by following the market back down.

The graph shows the FOMC’s longer-run projections before and after the soft landing. “The longer-run projections are the … federal funds rate to which a policymaker expects the economy to converge over time in the absence of further shocks and under appropriate monetary policy. They represent “the value of the midpoint of the projected appropriate target range for the federal funds rate or the projected appropriate target level for the federal funds rate at the end of the specified calendar year or over the longer run… For each period, the median is [usually] the middle projection.” The three highest funds rate targets represent the high end of the range shown as a green dotted line; high targets are shown in orange. Note that the median FOMC targets never anticipated a fed fund rate lower than 2.5% (median) or 3% (high). Some still speak of a 2.5% fed funds rate as a mystical “neutral” goal.

The yield on 2‑year Treasuries (the red line) clearly anticipated each uptick in the federal funds rate (in black), and jumped far ahead of the Fed by November 8, 2018, when the 2‑year yield of 2.98% was well above the 2.25% ceiling on fed funds. Despite slipping bond yields, the Fed nonetheless raised the top of its fed funds rate to 2.5% on December 21 and kept it there through July 30, 2019. But by then 2‑year yield had dropped to 1.85% leaving the yield curve sharply inverted with overnight interest rates on bank reserves sharply higher than the return on 2‑year Treasuries.

In early 2019, the FOMC central planners did not change their mind about a minimum (or “neutral”) fed funds rate of 2.5%. But the world market for short-term bonds knew the economy could not sustain that high a fund rate, so the yield curve inverted. Since banks borrow short and lend long, the Fed had to either back-off of its green line ambitions for the funds rate or watch an increasingly inverted yield curve collapse lending and the economy. The Fed backed off, so the landing was soft – until the COVID pandemic and lockdown collapsed world production and commerce in ways that still severely constrain supply capacity.

What (aside from an unexpectedly bad global recession) might, as in 2019, cause the Fed to rethink its current schedule of repeated 50–75 basis point interest rates increases for some undefined period?

An end to war in Ukraine and related commodity supply losses would help. So would and end to crippling export lockdowns in China. However, since the Fed claims to be targeting core PCE inflation, simply a sustained continuation of the slowdown in core U.S. consumer inflation we saw this February and March really ought to suffice.