Although dedicated Fed watchers long saw it coming, the big news from Jackson Hole is that the Fed now has a new monetary policy strategy—the crowning achievement of the much-ballyhooed review of its “Strategy, Tools, and Communications” it launched in early 2019. It’s called “average inflation targeting,” and chances are that if you’re reading this you’re wondering (1) what the heck it means and (2) what, if any, difference it will make.

Don’t feel bad. More than a few seasoned monetary economists have been asking themselves the same questions, myself included. Having come up with some answers, I thought to share them with you, together with my reasons for concluding, first, that the new strategy isn’t likely to improve things; and, second, that the Fed has missed a chance to adopt a different strategy that really would work better.

Falling Short

The best way to understand average inflation targeting (henceforth, AIT) is to first understand what the Fed was up to before Powell’s announcement. That requires knowing both what it intended to do and what it did in fact.

Concerning what the Fed intended to do, starting in late January 2012, and until quite recently, it was committed to stabilizing inflation “at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures.” Doing that, Fed officials concluded, would serve to keep the public’s “longer-term inflation expectations firmly anchored,” presumably at the same, 2 percent level.

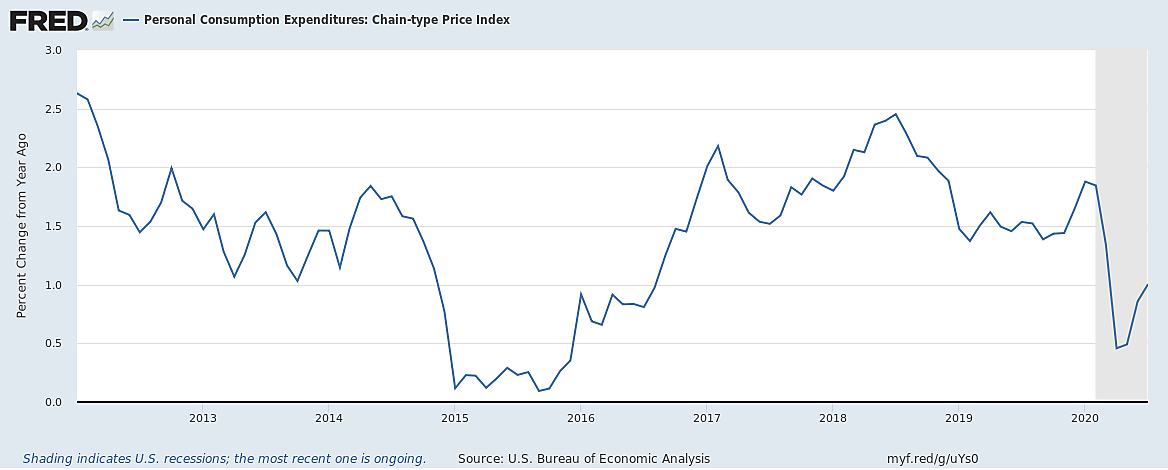

So much for intentions. As the following chart makes clear, what the Fed did in fact, albeit unintentionally, was allow inflation to frequently fall well below its target level:

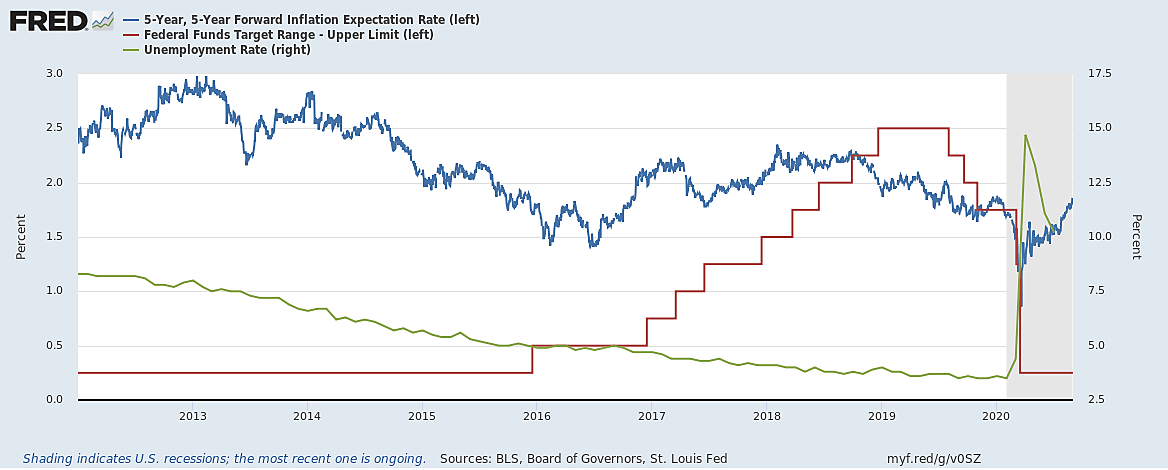

That the Fed routinely fell short of its inflation target doesn’t mean that it simply tossed the target aside. On the contrary: to judge from market participants’ own inflation expectations, as reflected in the TIPS spread, the Fed generally adjusted its policy stance in a manner consistent with achieving its 2 percent inflation going forward. Its calculations only proved mistaken after the fact. As the next chart shows, the one clear exception to this occurred in December 2015, when the Fed raised its rate target for the first time since the 2008 crisis, when the expected 5‑year forward inflation rate was well below target. That decision appears, by the way, to have been due more the Fed’s decision to prematurely begin raising the fed funds rate to an overestimated “normal” value, than to any naïve Phillips Curve reasoning. (See this Twitter thread.)

Many Misses are as Good as a Mile

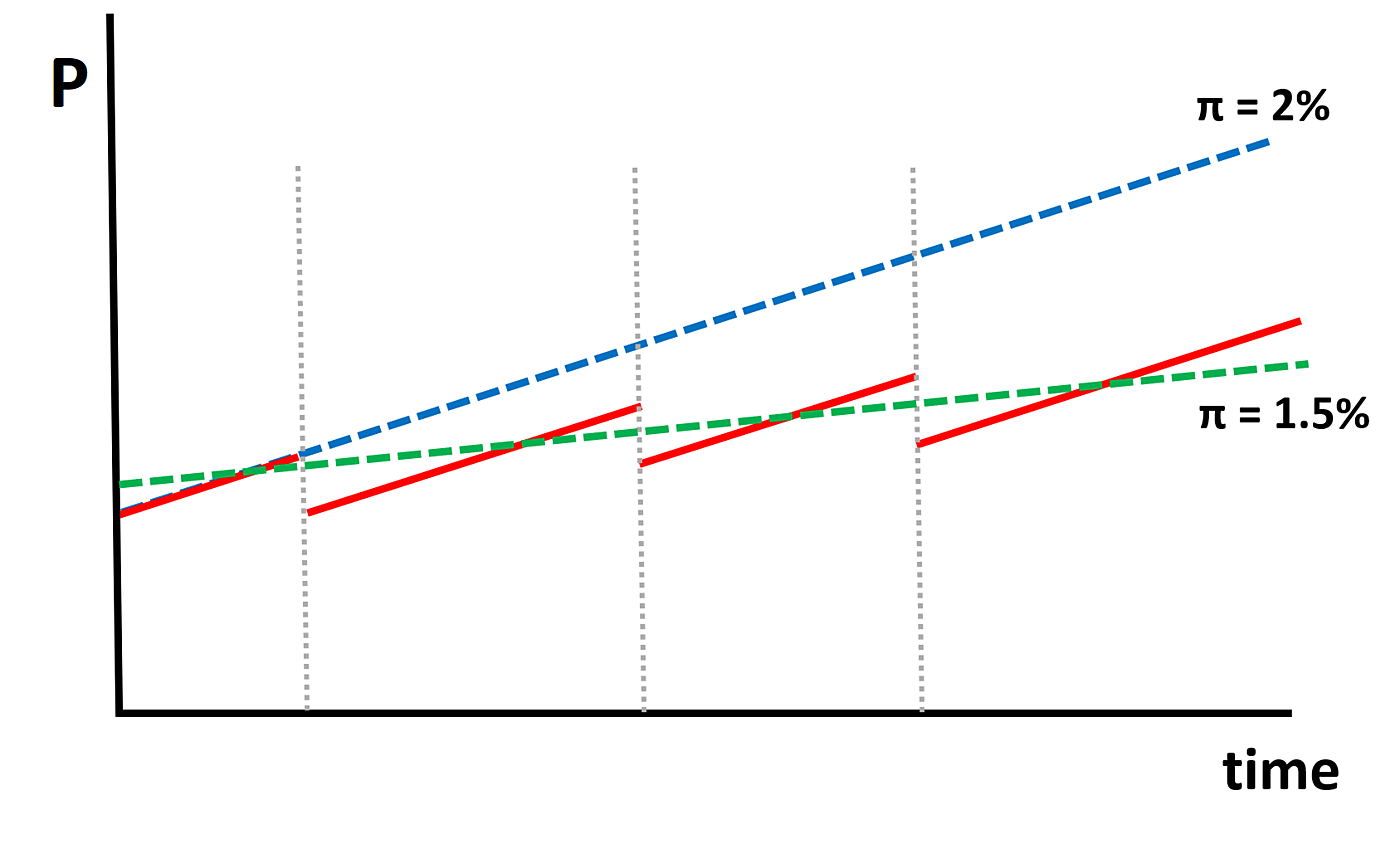

If the Fed was (almost) always setting its policy stance so as to keep the expected inflation rate close to 2 percent, what more could one ask of it? Plenty, actually. That becomes clear once one distinguishes between the path of the expected rate of inflation on one hand, and that of the actual price level on the other. To take a simple case, suppose that the Fed has a 2 percent inflation rate target, and that at each FOMC meeting it sets that target where it thinks it needs to be to get the price level to increase by 2 percent over the coming years. Suppose also that the public agrees with the Fed’s decision, so that the expected inflation rate at each rate setting is also 2 percent. If all goes according to plan, the price level will never veer from its 2 percent path.

But suppose that the economy experiences a series of unexpected shocks that put downward pressure on prices. These could be either negative demand (velocity) shocks or positive supply shocks. Suppose as well that those shocks aren’t matched by corresponding shocks of the opposite sort. The Fed, in other words, faces a “run” of negative price level surprises. In that case, although it continues to set its rates at levels calculated to keep the forward-looking inflation rate at its 2 percent target, the ex-post or “backward-looking” inflation rate will be persistently below that target; and the longer that run continues, the larger will be the gap between actual and intended inflation. The chart below, with the price level (P) as its vertical axis, and time as its horizontal axis, shows the case where each of three adverse demand shocks, occurring at the dates marked by horizontal grey lines, causes a downward shift of the price-level from its original target path, represented by the dashed blue line, where the slope (π) of that line represents the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target. After each shock, prices once again rise at the Fed’s target rate (red lines). Consequently, the ex-post inflation rate, represented by the slope of the dashed green line, is 1.5 percent, or 50 basis points below the targeted rate represented by the slope of the dashed blue line. Although future shocks might shift prices higher, offsetting this undershooting, there’s no reason to suppose that they’re bound to do so.

Average is (Sometimes) Over

The upshot of all this is that steering monetary policy differs from steering a car in at least one crucial respect, namely, that whereas you can keep a car on course without ever glancing at the rear-view mirror, an inflation-targeting central bank that only looks ahead can end up badly off course. A still better analogy would be with setting a ship’s course: getting the right bearing (compass direction) is seldom enough. As a ship gets buffeted by winds and currents, adjustments have to be made to compensate for drift.

Such adjustments are what Average Inflation Targeting is all about. In the abstract, the idea couldn’t be simpler: to set its course going forward, the Fed takes account of how far it has drifted off course in the past. That means aiming for an inflation rate below its long-run target whenever it finds that inflation has drifted above that target, and aiming for a rate above its long-run target whenever it finds inflation has drifted off course in the opposite direction. Put in practice today, AIT would mean setting a course for above-target inflation, to make up for the below-target inflation the Fed has allowed in the past.

So much for the abstract theory. Translating it into practice is where things get tricky, as there are all sorts of ways for doing so, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

The most obvious choice that has to be made concerns how far backwards the Fed should look. After all, an “average” has to be an average taken over a certain number of observations. Will the Fed achieve an average rate of inflation equal to its long-run target over a span of two years? Three? A decade? How far back will it look in setting its future course, and how long will it allow itself to take to make up for any past drift?

Such choices are especially fraught when AIT first goes into effect, for it’s precisely then that the time choices are likely to matter most. A long interval of strictly forward-looking policy has allowed the price level to drift far from its originally-targeted path. The further back the Fed chooses to look now, the greater the adjustments it may have to make, and (because these adjustments are likely to take time) the longer its overall averaging window must be. The less far it looks, the less its new policy will differ from strict (that is, strictly forward-looking) inflation targeting (SIT). Either way, it may prove difficult for the Fed to convince the public that anything has changed.

Catching Powell’s Drift

So, what precise approach to AIT does the Fed have in mind? The disappointing answer is… no precise approach at all! “In seeking to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time,” Powell said in his Jackson Hole speech, “we are not tying ourselves to a particular mathematical formula that defines the average. Thus, our approach could be viewed as a flexible form of average inflation targeting.”

In other words, just about anything is possible. The Fed might even go on with its SIT strategy (assuming that’s what the Fed has been up to), since (as Stephen Cecchetti and Kermit Schoenholz explain) SIT amounts to a special version of AIT with a trivially short “averaging window.” Or it could allow the inflation rate to wander either well above or well below its long-run target, restrained only by a vague promise to rein it in “eventually.” In short, to return to our nautical analogy, it’s not clear that the Fed has done anything other than grant itself more leeway.

“In theory,” Norbert Michel writes,

making up for past misses is a good thing, but the flexible nature of this new policy makes it very difficult to know exactly what the Fed will do as economic conditions unfold. …It is also rather disappointing because, after basically a decade of being unable to hit its inflation target, the Fed has essentially broadened its definition in a way that ensures it can’t miss.

Can’t miss, that is, even if it keeps doing just what it’s been doing all along—or worse. As Tim Duy observes in his own, trenchant critique of the Fed’s new strategy, because it allows the Fed to miss its inflation target “by an unspecified magnitude for an unspecified period of time,” the Fed’s open-ended version of AIT “has unanchored policy expectations by creating uncertainty around what it means to meet its inflation target,” leaving market participants at sea “until further guidance is provided.”

Inflation Expectations and the ZLB

That almost anything is possible with the Fed’s particular version of AIT doesn’t mean that AIT couldn’t possibly improve things. According to its champions, if implemented correctly, AIT could help the Fed overcome the “Zero Lower Bound” (or ZLB) problem. That problem arises when the Fed’s policy rates are already at or very close to zero, and negative rates aren’t an option. If inflation is still too low or unemployment is still too high, or both things are true (as has been the case recently), the ideal policy rate is presumably somewhere below zero. Yet the Fed can’t go there. Instead it’s “stuck” at the ZLB.

How might AIT help? The explanation has to do with the fact that, other things equal, any increase in the expected rate of inflation lowers “real” (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. It follows that an increase in expected inflation amounts to an easing of monetary policy even when the Fed’s policy rate is stuck at zero. AIT might offer a built-in solution to the ZLB problem, because any initial over-tightening leads to a corresponding upward adjustment in inflation expectations, and hence to a lowering of anticipated real interest rates, which serves as an effective alternative to lower nominal rates.

Whether this potential advantage of AIT will be of any use in practice is another matter. In their November 2019 Peterson Institute Policy Brief, David Reitschneider and David Wilcox observe that, even with a relatively aggressive form of AIT, the flatness of the present-day Phillips Curve means that, after a bout of undershooting, getting back to a targeted average inflation rate may instead be more a matter of time than of any substantial inflation overshooting. And the time required could well be more than a decade. Consequently the ability of AIT to relax the ZLB constraint will depend not only on the strictness of the AIT rule but on the public’s willingness to believe that the FOMC will stick to that rule “for many, many years into the future—a debatable proposition.”

An Incredible Commitment

If AIT has potential advantages, it also suffers from at least one serious drawback. That drawback becomes evident when, instead of having to make up for a period of below-target inflation, the Fed has to do the opposite.

Suppose, for instance, that several unexpected, positive demand shocks drive the inflation rate to 3 percent for a time. Eventually the shocks cease, and the rate returns to 2 percent. Under AIT, that return doesn’t suffice: the Fed has to tighten further, so as to drive the inflation rate below 2 percent long enough to get the price level back to its original, 2 percent path. But the correction comes at the cost of a temporary reduction of employment and output, which both the public and the government are bound to resent. “Imagine the Fed Chair,” Brookings’ David Wessel writes, “explaining at a press conference that the Fed was going to raise interest rates and increase unemployment to compensate for a period at which inflation was too high and unemployment too low.”

In their previously mentioned Policy Brief, Reitschneider and Wilcox supply an example of how AIT might have led to exactly the sort of impasse Wessel describes had the Fed resorted to it in the past. Had the Fed pursued an aggressive 5‑year AIT strategy during the mid 2000s, based on headline Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation, Reitschneider and Wilcox calculate that the oil shock that took place then would have compelled it to keep “the federal funds rate near 8 percent even as the housing market collapse, financial stress intensified, and the economy slipped into recession.”

Faced with stiff-enough opposition, the Fed might fail to carry out some or all of a needed correction, undermining the credibility of its policy commitment. Because the Fed’s efforts to make up for excessively low inflation are less likely to meet with similar opposition, the result could be an “asymmetrical” average inflation targeting strategy that allows the price level path to drift upwards. In that case, even if the Fed starts out with a clearly-specified AIT rule, its reluctance to stick with it will cause the long-run inflation rate to exceed the Fed’s target, while making the future course of the price level just as unpredictable as it is under strict inflation targeting.

And a Missed Opportunity

AIT is only one of several alternatives to conventional inflation targeting the Fed claims to have considered during its review. Another is nominal GDP level targeting (NGDPLT), which seeks to keep total spending on final goods, rather than the PCE index, on a fixed upward trend. Although the Fed hasn’t made public its reasons for favoring AIT over NGDPLT, it may have been won over by arguments Lars Svensson makes in a paper he presented at the June 2019 Chicago Fed conference. So far as I’m aware, Svensson’s was the only paper addressing these choices to be featured in the course of the Fed Listens events.

Last October, I pointed to what I consider to be several serious shortcomings of Svensson’s arguments. Here I wish to compare it to AIT, to see how they would differ in practice, and whether either offers any clear advantage over the other. To simplify the comparison, I’ll consider price-level targeting (PLT), which as we’ve seen is but a strict version of AIT. Because NGDPLT and PLT involve identical responses to demand shocks, to compare the policies and decide which is best, we only need to consider how each would have the Fed respond to positive or negative supply innovations, including both shocks to the (“natural”) level of output and changes in its growth rate relative to some past trend.

For one-time (level) supply shocks, the answer to the question is very simple: whereas PLT has the Fed fully and rapidly make up for any deviation from a given price-level trajectory, whether it stems from a demand or supply shock, NGDPLT does not call for it to make up for deviations stemming from supply shocks. Instead, so far as one-time supply shocks are concerned, NGDPLT resembles strict inflation targeting (SIT) in letting bygones be bygones.

For growth rate changes, the answer is distinct, but analogous. Whereas PLT calls for monetary easing to counter what would otherwise be an altered inflation rate, NGDPLT once again calls for no change in the Fed’s stance. Instead, it allows the inflation rate to increase when the output growth rate declines, and to decline when the output growth rate increases.

So, which is better, PLT or NGDPLT? Let’s first consider their relative merits as means for addressing output level shocks. In an article assessing price-level targeting, George Kahn offers an implicit comparison:

The major cost of a price-level target comes from supply shocks—shocks such as an increase in oil prices that push the price level up and cause output to fall. Under a price-level target, these shocks would lead the central bank to tighten policy to extinguish the impact of the shock on the price level. This, in turn, would further exacerbate the decline in output. In contrast, an inflation-targeting central bank would “forgive—and forget” shocks to the price level. The result would be a permanent shift in the price-level path, but with less short-run inflation and output volatility. Thus, a price-level target could lead to greater variability in inflation and output over the short run compared with an inflation target.

Bearing in mind that, so far as supply shocks are concerned, NGDPLT is equivalent to SIT, Kahn’s assessment amounts to a verdict in favor of NGDPLT: an oil shock like that of 2007, which would have proven so disastrous to an average inflation targeting Fed, would have posed far less of a challenge to one committed to NGDPLT. Because it mimics PLT’s response to demand shocks, and SIT’s response to supply shocks, NGDPLT succeeds in doing better than either.

NGDPLT may be said to offer a similar advantage in the case of output growth rate innovations. But here it also has a further advantage, namely, a superior ability to assist the Fed in steering clear of the ZLB. To understand why, consider that the zero lower bound has become binding chiefly owing to a secular decline in the real neutral interest rate. And that decline is largely due to a declining rate of productivity growth. Given some fixed target long-run inflation rate, and assuming that by the Fed’s strategy, whatever it is, keeps the expected rate of inflation roughly equal to that target rate, the neutral nominal interest rate will also decline as productivity growth declines. The lower that neutral nominal rate, the greater the risk that the Fed finds itself stuck at the ZLB.

Now consider: under AIT, the long-run inflation target is independent of both the real neutral rate, and the productivity growth rate that informs it. Under NGDPLT, in contrast, the (implicit) inflation target varies inversely with any change in the rate of productivity growth, and so will expected inflation once the change is recognized. Consequently, a reduction in the growth rate of output that lowers the real neutral rate need not lower the long-run, nominal neutral rates. NGDPLT thus reduces the risk that future reductions in productivity growth will cause the ZLB to bind more often.

To conclude: after frequently falling-short of its inflation target, the Fed now promises to make up for it, by switching to average inflation targeting. Whether the new strategy does any good remains to be seen. But even if it does, by choosing AIT over NGDPLT, the Fed has missed yet another mark. Here’s to hoping that, some day, it makes up for that miss as well.

[Cross-posted from Alt‑M.org]