A new report from the Government Accountability Office finds that virtually every one of the 1.2 million employees in their study received a rating at or above “fully successful,” compared to only 0.1 percent who were deemed “unacceptable,” which might be surprising given the scandals that have rocked multiple agencies in recent years and the fact that these employees are people, prone to making mistakes or every day struggles like everyone else. Milton Friedman once asked “where in the world you find these angels who are going to organize society for us?” If these performance ratings are to be believed, they’re already in the federal workforce, which might surprise anyone who has followed the developments at the VA or TSA. The extremely skewed distribution of ratings highlighted in the report highlight the shortcomings of the current evaluation system, which makes it harder to actually address any real problems with the performance of federal employees.

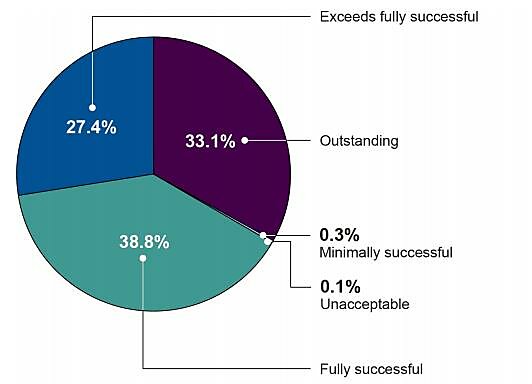

Distribution of Performance Ratings, 2013

Source: GAO

Note: Ratings for permanent, non-senior executive service employees.

The authors of the report used data from the Office of Personnel Management to analyze performance ratings for permanent, non-Senior Executive Service employees who received a rating for fiscal year 2014. While there are some exclusions, like the U.S. Postal Service and intelligence agencies, the 24 agencies included “are generally the largest federal agencies and account for more than 98 percent of the federal workforce.” According to the ratings, not only are there virtually no underperforming employees, but many of them go above and beyond the call of duty: 27.4 percent were rated as “exceeds fully successful” and a remarkable 33.1 percent received the highest rating of “outstanding.” While agencies use ratings systems with different numbers of levels, the pattern remains the same: almost every employee rates as “fully successful” or above, with roughly 0.1 percent rating as “unacceptable.”

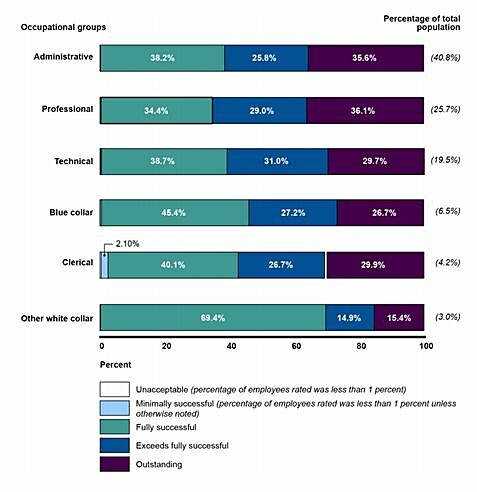

Things are even rosier when breaking the ratings down by occupational category. The clerical group, which accounts for 4.2 percent of these workers, is the only one of six occupational categories where more than one percent of workers received either an “unacceptable” or “minimally successful” rating. According to the feedback from the ratings systems, coming across a less than stellar federal worker in the administrative, professional, or technical fields is like finding a needle in a haystack. These federal workers are people, fallible like anyone else, so a distribution so heavily skewed towards positive ratings makes the system less credible.

Distribution of Performance Ratings by Occupational Category, 2013

Source: GAO

Note: Ratings for permanent, non-senior executive service employees.

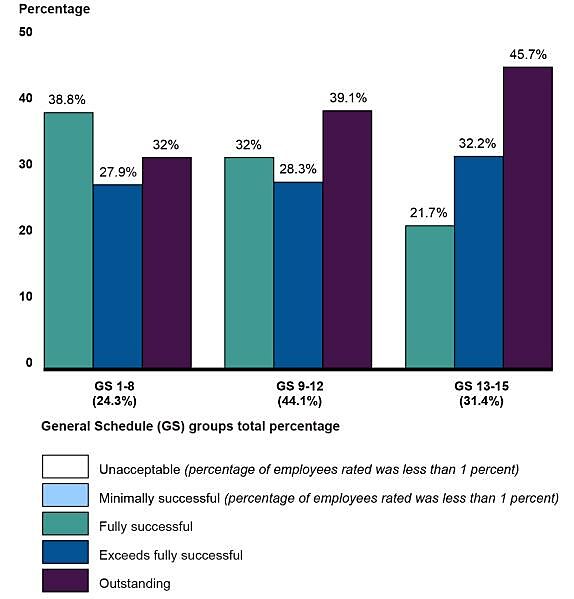

The performance feedback is even more skewed towards stellar when the authors look at workers in higher grades of the General Schedule. Roughly 78 percent of workers in the highest group received one of the top two ratings, compared to 0.4 percent who received anything less than “fully successful.”

Distribution of Performance Ratings by GS Group, 2013

Source: GAO

Note: Ratings for permanent, non-senior executive service employees.

The authors delve into some of the difficulties in trying to normalize the ratings system from a situation where nearly everyone is a top performer: “[a] cultural shift might be needed among agencies and employees to acknowledge that a rating of ‘fully successful’ is already a high bar and should be valued and regarded and that ‘outstanding’ is a difficult level to achieve.” When more than a third of the covered federal employees, and roughly 46 percent of higher level GS employees received this “outstanding” rating, the system loses much of its value. At this point, the ratings have more in common with the participation trophies found in little league than a meaningful feedback system to address shortcomings and improve performance. In one sense, taxpayers aren’t the only ones done a disservice by this poorly functioning system, as more competent federal workers are indistinguishable from their less able peers, and promotions cease to be based on things related to actual job performance. Having a functional evaluations system is even more important outside of the private sector, where market forces convey valuable information about which methods and employees are successful through profits and losses. As my colleague Chris Edwards has explained, the absence of these market mechanisms one of the reasons for the failures in federal bureaucracy.

As this report notes, the “transparency and credibility of the performance management process is enhanced when meaningful performance distinctions are made.” Given the government’s problems with transparency and credibility in so many other spheres, is it any surprise that the performance evaluation system struggles with the same issues? Until these agencies are able to address this “long-standing challenge,” it seems we’ll just have to take their word for it that virtually every one of these federal employees is above average, and hundreds of thousands are “outstanding.”