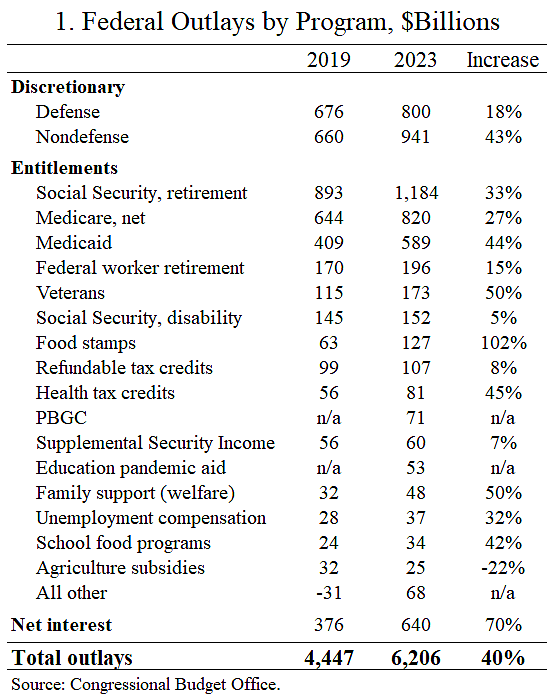

Federal spending jumped from $4.45 trillion in 2019 to $6.21 trillion in 2023, according to the Congressional Budget Office. That is a 40 percent increase in four years. The pandemic supercharged the federal budget, and spending and deficits are expected to continue rising unless policymakers pursue major reforms.

What is all the new spending since 2019? The answer is surprising, as shown in the two tables below. The main drivers of the recent increases have not been the largest three programs—Social Security, Medicare, and defense—but rather rapid growth in numerous other programs.

Table 1 shows CBO spending for 2019 and baseline estimates for 2023. The largest increases have been nondefense discretionary, Medicaid, veterans, food stamps, health tax credits, welfare, school food programs, and interest. All data in both tables are fiscal year outlays.

Some of the 2023 spending is temporary and should decline in coming years, such as the PBGC aid and education pandemic aid. Nonetheless, CBO projects baseline spending to rise at an annual average rate of 4.8 percent over the coming decade. The projections show that Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid will be the main growth drivers ahead, but the past four years show that other programs will also grow rapidly if not controlled.

What about Ukraine? CRFB tallies the total authorized (but not necessarily spent) funding so far as $67 billion for defense aid and $46 billion for nondefense aid. If I am reading CBO correctly, they estimate that about $36 billion of the defense aid will be spent this fiscal year.

Table 2 shows spending data from President Biden’s recent budget broken out by major agency. The budget puts the increase between 2019 and 2023 at 43 percent, and Biden is proposing an 8 percent increase for 2024. The data are from Table 4.1 here.

What programs are behind the largest increases in the table? Agriculture: food stamps. Education: college aid and pandemic school aid. HUD: numerous programs. Labor: PBGC aid to troubled pension plans. Treasury: interest costs. EPA: state grants. International Aid: Ukraine. SBA: disaster loans.

Republicans led the way on spending increases in 2020, and then handed the big government baton to the Democrats for 2021 and 2022. Now some Republicans want to reverse course and leverage the upcoming debt limit debate to start cutting. What should they target?

How about a “last in first out” strategy? Reformers could push for cuts to the programs that have grown the most since 2019. Medicaid, food stamps, education aid, housing programs, welfare, the EPA, and international aid would all be good targets to downsize.

By the way, outlays from 2019 to 2023 are up 47 percent for the operations of the legislative branch and 58 percent for the Executive Office of the President. How about these institutions showing some budget leadership and cutting their own costs?

Recent commentary on federal spending is here and here, and further proposals to cut spending are here, here, and here.

Data Note. The “all other” row in Table 2 is the net of other spending programs and hundreds of billions in offset receipts, which are explained here.