Economists are blaming today’s high inflation on excess federal spending, supply disruptions, and misjudgments by the Federal Reserve. With inflation running at 8 percent, the Fed clearly failed its mission to hold inflation to 2 percent.

John Cochrane noted that the Fed “was completely surprised by the surge of inflation, and through most of [2021] insisted it would be ‘transitory,’ and go away on its own. That turned out to be a major institutional failure.” Jim Dorn argued, “The Fed’s forecasts, based on complex economic models of the economy, have been error‐prone for years.”

Another problem appears to be that the Fed misreads how the economy works. The editors of the Wall Street Journal argued that part of the blame for inflation “lies with the Fed’s economic models, which are rooted in Keynesian analysis in which demand trumps all. The Fed models give little thought to incentives for or barriers to the supply-side.”

The Journal continued that, “The Fed is supposed to have the world’s smartest economists and access to the best financial information. How could they make the greatest monetary policy mistake since the 1970s?”

Government mistakes are usually blamed on underfunding, but the Fed can’t make that claim. The “world’s smartest economists” come with a price tag, as revealed by data in Fed budgets and statistical tables.

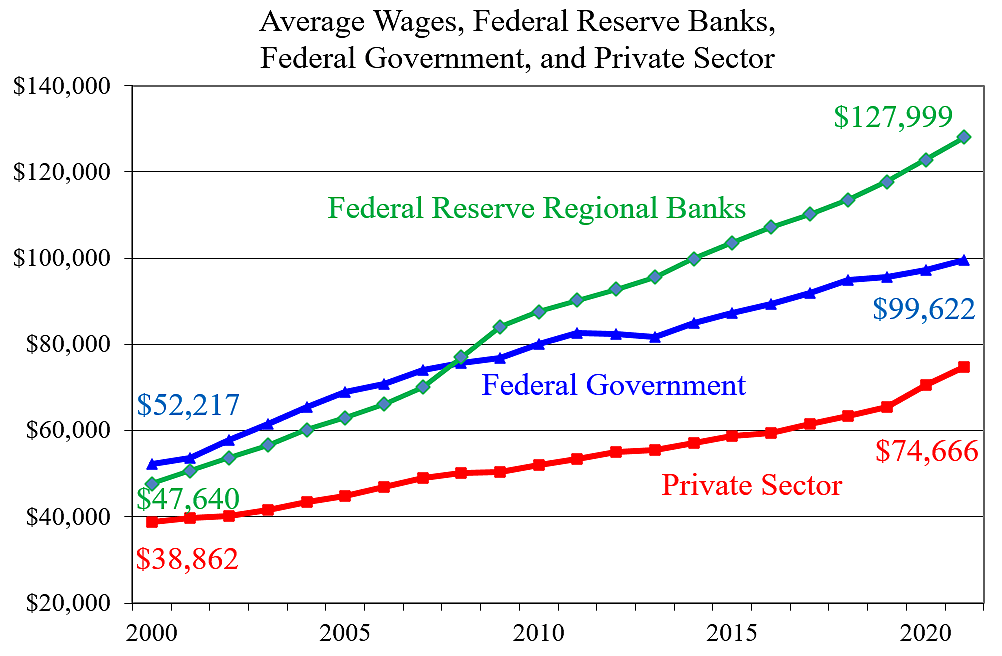

The Federal Reserve System includes the Board of Governors and 12 regional banks. In 2021, the Board had 2,973 employees who earned an average wage or salary of $168,786. The regional banks had 20,141 employees who earned an average wage of $127,999.

On top of those wages are the Fed’s generous benefits, which pushed average Board compensation up to $215,338 in 2021, and average regional bank compensation up to $193,123.

The chart shows average wages of employees in the regional banks compared to average wages in the federal government and private sector, which I explored last week. Average wages in the regional banks have risen rapidly, with a particularly large jump in 2008 and 2009.

These data are averages and thus reflect not just growth in salaries for particular jobs but also the changing composition of workforces. The Fed’s 2010 annual report noted that the regional banks had substantially reduced staff in check-processing activities, and thus apparently eliminated relatively lower-paying positions.

There have also been changes at the top end of the regional banks. The number of “officers” in the banks jumped 72 percent from 1,063 in 2000 to 1,833 in 2021. In 2021, officers made an average wage of $261,266.

The Fed’s regional bank workforce fell from 23,056 in 2000 to 17,015 in 2010, and then it rebounded and grew to reach 20,141 by 2021.

Meanwhile, the number of Board employees soared 76 percent from 1,691 in 2000 to 2,973 in 2021. The Fed has become more top heavy with a larger bureaucracy in Washington.

How does all this affect the general public? The public ultimately pays the Fed’s costs, including compensation costs. That’s because more costs result in less Fed profits flowing to the U.S. Treasury. The GAO explained: “The Federal Reserve is a self‐financing entity that deducts its expenses from its revenues and transfers the remaining amounts to the U.S. Treasury. Because an additional dollar of Federal Reserve cost is an additional dollar of lost federal revenue, the costs of operating the Federal Reserve System are borne by U.S. taxpayers just like the costs of any federal agency.”

The Fed is a monopoly, so it would not be surprising if it had a bloated bureaucracy. The Board and regional banks have 23,114 employees, which compares to about 10,000 for the central banks of France and Germany. European countries also support 3,500 employees in the European Central Bank. In Canada, the central bank has just 2,050 employees.

I favor cutting every federal agency, including the central bank. But the real Fed experts are in the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives. In a new essay, director Norbert Michel argues, “Congress has given the Fed too many responsibilities,” and he suggests ways to narrow the bank’s mission and cut costs. With a simpler monetary policy framework and reduced regulatory role, a slimmed-down Fed could deliver more stable macroeconomic policy while opening the doors to greater innovation in financial markets.

Data notes: Average wages are calculated from the total salary costs provided in Fed budgets and statistical tables combined with the number of employees. Average total compensation for Board employees is based on the “salaries and other benefits” figure, and average total compensation for regional bank employees is based on the “personnel services” costs. For 2021, the budget and statistical tables are here and here. For 2000, see here and here. Ilana Blumsack contributed to this article.