The public is concerned that governments are providing excessively generous compensation to their workers. Attention has focused on the high salaries and benefits of federal civilian employees and the often lavish pensions paid to state and local workers.

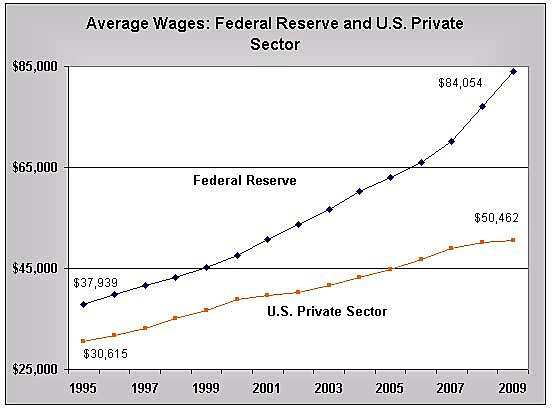

The compensation policies of the Federal Reserve System also deserve scrutiny. The chart compares average wages of workers in the U.S. private sector and workers in the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. In recent years, the average wage in the Fed’s regional banks has soared, reaching $84,054 in 2009, or 67 percent greater than the private sector average wage of $50,462. Meanwhile, the average wage of the 2,100 workers in the Fed’s Board of Governors in Washington reached $116,030 in 2009. (Federal Reserve Bank data is from this annual report table. Private sector pay is from the BEA, as discussed here).

However, there is a major caveat to this Federal Reserve Bank data. Bank employment has fallen from a stable level before 2002 of about 23,000 to just 17,398 in 2009. One reason is that a major Fed activity—check processing—is rapidly declining due to technological changes. Thus, it is likely that many lost Fed jobs were at relatively lower salary levels.

Nonetheless, despite a 26 percent workforce reduction since 1995, overall Fed Bank compensation costs (wages and benefits) have grown just as fast as the overall economy. Fed compensation costs doubled between 1995 and 2009 as U.S. GDP doubled. The Fed’s total current operating expenses—including compensation, buildings, etc—also doubled during this period. (The Fed’s expenses are from this table in its annual reports. I excluded the new “interest on reserves” expense).

In 2009, total average wages and benefits of Fed Bank workers was $124,974, or more than double the $61,051 average compensation in the U.S. private sector. Fed workers have very generous benefits, including rare perks such as subsidized cafeteria meals.

Let’s look at top end of the Fed’s workforce. In 2009, the average salary of the Fed’s 12 regional presidents was $340,323. In addition, there were 1,183 “officers” in the Fed Bank system with an average salary of $198,960, which is up 94 percent from the average officer salary in 1995.

Also note that the number of these high-paid “officers” in the 12 Fed Banks increased 25 percent between 1995 and 2009 (950 to 1,183), even as the number of overall Fed employees fell 26 percent, as noted. The system is thus becoming very top-heavy.

Federal Reserve annual reports are available online back to 1995. But a 1996 report from the Government Accountability Office discussed the fairly rapid rise in Fed operating expenses during the 1988 to 1994 period, thus indicating that rising costs have been an issue for some time.

How does this affect the general public? Rising costs result in fewer central bank profits being transferred to the U.S. Treasury. That means higher federal deficits or taxes. The GAO explains:

“The Federal Reserve is a self-financing entity that deducts its expenses from its revenues and transfers the remaining amounts to the U.S. Treasury. Because an additional dollar of Federal Reserve cost is an additional dollar of lost federal revenue, the costs of operating the Federal Reserve System are borne by U.S. taxpayers just like the costs of any federal agency.”

As a monopoly immune from competition, the Fed will tend to have a bloated bureaucracy. That makes oversight by Congress very important so that technological efficiencies gained in Fed functions such as check-clearing are passed along to taxpayers, and not gobbled up, for example, by rising numbers of high-paid officers. As the Congress next year looks for ways to reduce the budget deficit, it should look for cost savings at the Fed.

Policymakers might consider whether the Fed really needs 12 regional bank organizations, each with huge fortress-like buildings in cities across the nation. They should ask why the number of high-paid “officers” has increased, even as the number of overall Fed workers has fallen. And they should ask whether Fed employees really need such generous benefit packages—including, for example, both a defined contribution and a defined benefit plan.

I’m not convinced that we need a monopoly central bank. But until policymakers explore alternatives such as free banking, they should try to reduce costs at the Fed as they scour the entire budget for savings.

(Assistance was provided by intern Michael Nicolini).