Throughout the pandemic, people have poured into states in the south and intermountain west, including states like Idaho, Arizona, and Utah. According to Census Bureau estimates, areas including Boise, Idaho and Salt Lake City, Utah sustained some of the highest net migration increases during the 2020–2021 period.

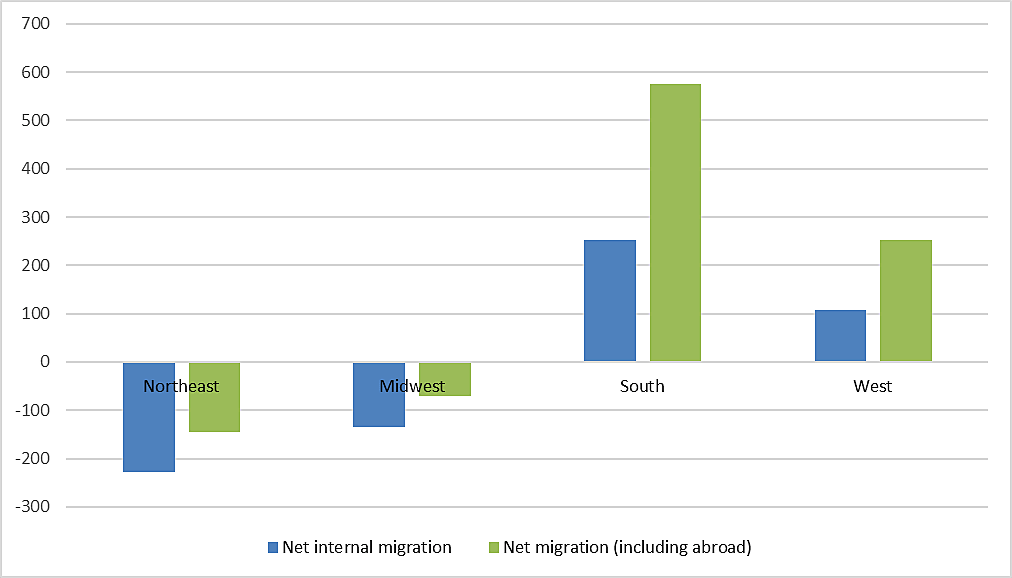

Figure 1. U.S. regional migration, 2020–2021, numbers in thousands

Source note: Net internal migration encompasses migration to/from U.S. states. Net migration includes migration from abroad. California has some of the highest outbound migration of any state; this depresses net migration estimates for the West. Table A‑2: Annual Inmigration, Outmigration, Net Migration, and Movers from Abroad for Regions: 1981–2021

Following increasing in-migration, cities in these once-affordable states rapidly encountered housing affordability issues. For example, at the end of June 2022, Phoenix, Arizona and Salt Lake City, Utah had monthly mortgage payments that were up over 70 percent, year-over-year. Observed rents were up 15 percent year-over-year in the same areas (having fallen from their peak of 20–25 percent).

Various factors—including changing consumer needs, supply chain issues, labor shortages, and the like—combined with rising demand to produce rising prices. In addition, policies including restrictive zoning became newly salient in western states with burgeoning population growth.

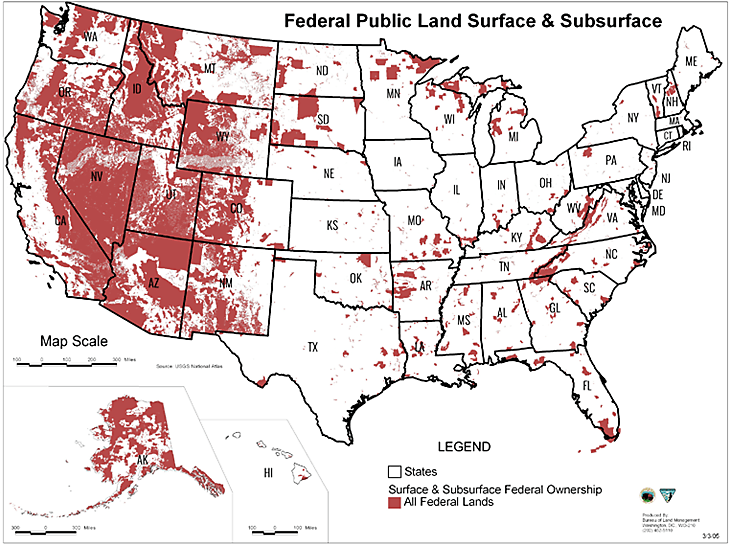

However, there is another less-recognized policy issue affecting housing supply that is specific to western states: a substantial portion of the land is owned by the federal government and not developable.

For example, in Nevada, Utah, and Idaho, the federal government owns more than 80 percent, 63 percent, and 60 percent of the land.[1] In other states like Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, California, and Montana, the federal government owns more than one-third to one-half of available land.

Contrary to public perception, the vast majority of federal lands are not national parks, monuments, or Bureau of Indian Affairs land. Instead, a majority of federal western land is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service (USFS).

BLM land was once described as “land that nobody wanted” owing to the fact that homesteaders had passed over it. Today, BLM and USFS land is used for a variety of uses, including grazing, mining, recreation, and energy transmission and production.

This land is not so far from urban development that it is of no practical use, and a significant portion of lands are within city or county boundaries: previous estimates indicate that there are 217,000 acres of BLM and USFS land within Utah city boundaries, and 650,000 acres of USFS and BLM lands within one mile of Utah city borders.

Presented with a similar set of facts in the 1990s—Las Vegas, Nevada was the fastest growing metropolitan area at the time and landlocked by federal lands punctuating private property—federal legislators passed a bill that allowed local governments in the Clark County, Nevada area to nominate federal land for competitive market auction.

Figure 3. Example of typical federal land sold to private parties in the Las Vegas metro area

Source: SNPLMA: A Model for Success, Department of the Interior

The sale of federal land in the Clark County area subsequently resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars being allocated to Nevada public schools and more than a billion dollars allocated to Nevada’s trails, parks, and natural areas, creating an unusual win-win for Nevada developers, conservationists, and residents alike.

Earlier this year, Senator Lee and cosponsors introduced the HOUSES Act, a bill with similar objectives but more specific focus on housing development than the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act (SNPLMA) of the ‘90s. The proposed HOUSES Act would allow local governments to nominate and purchase federal land and then develop the land for housing projects that meet certain density minimums and other criteria.[2]

Similar to SNPLMA, proceeds from HOUSES would be made available for environmental initiatives including improvements to existing National Parks, wildfire prevention programs, public water infrastructure projects, and restoration initiatives.[3]

But in spite of legislative efforts, the question remains: how much good could federal lands reform really do for housing affordability? This week, the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC) made a serious attempt to answer this question in a new report.

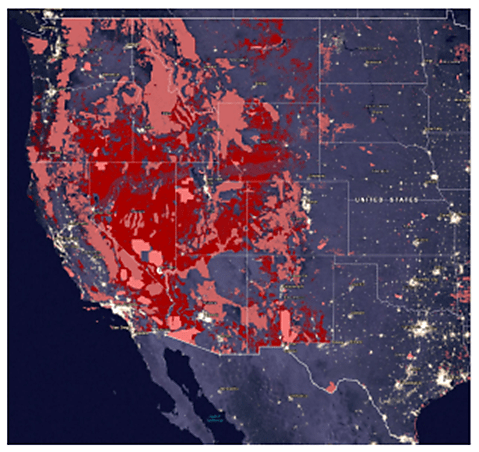

The JEC study first martials new figures and visuals indicating that federal land is, indeed, adjacent to many existing developed areas in western states. For example, one visual (Figure 4) highlights existing developed areas (white) and existing federal lands (both dark and light red). JEC finds that population per square mile significantly declines in many counties after accounting for federal land—what you would expect to find in places where development is constrained.

Figure 4: “Western States’ Population Centers at Night and Federal Land, 2021”

Source: The Houses Act: Addressing the National Housing Shortage by Building on Federal Land

The authors then evaluate the effect of federal land reform on housing. They estimate buildable federal land by limiting land to BLM-managed land and remove all remaining land parcels containing water, marshland, or a slope greater than 15 degrees that would make development challenging. Then, using various assumptions based on the HOUSES Act, the report models how many homes could be built on eligible buildable parcels before A) the available buildable land runs out or B) the so-called housing “shortage” is eliminated.[4]

JEC concludes that the HOUSES Act could significantly influence housing supply in western states. Specifically, the study finds that HOUSES reforms could lead to the construction of approximately 2.7 million homes, including 430,000 homes in San Diego County, California; 350,000 homes in Maricopa County, Arizona; 109,000 homes in Clark County, Nevada; and 55,000 new homes in Utah County, Utah alone.

As a result of this new development, the authors find that an additional 8 percent of the population in twelve western states would be able to afford an average home (a 24 percent increase from the baseline). Crucially, this increase in housing development would be possible with the conversion of just 0.1 percent of existing federal land holdings.

As the report acknowledges, federal land reform is in no way a substitute for zoning reform at the state and local government level. Moreover, the study’s estimates hinge on the implicated counties’ interest in, and use of, the proposed program: counties with strong environmental impulses may be less inclined to make use of the program.

Still, this study provides evidence that federal land reform could be a promising federal tool to improve housing supply and thereby housing affordability. This will likely come as welcome news to many western municipalities with housing markets under pressure from growth.

[1] These figures “understate federal lands in each state and the total in the United States” as “they include only land of the five largest land-managing agencies: BLM, FS, FWS, NPS, and DOD lands.” See CRS report.

[2] Purchase is subject to approval. Details about how local governments will disburse said lands to private actors, or otherwise initiate housing development, are not prescribed by the Act.

[3] Despite the positive effects of the SNPLMA on increasing developable land, Clark County, Nevada remains landlocked by federal lands.

[4] The authors acknowledge that “shortage” is an economically imprecise description, as homes can generally be purchased at the market-clearing price. Nonetheless, in this and another paper, the authors admit the term is still of practical use due to its prevalence in the national debate. Defining “shortage” as the number of homes that would be built absent supply constraints, they find that previous estimates understate housing supply problems because they take existing historical development trends as a given.