Regular Alt‑M readers are no doubt looking forward to the FOMC’s announcement next Wednesday. But I doubt they’ll be sitting at the edges of their seats between now and then, much less biting their fingernails.

Markets have, after all, been anticipating a modest Fed cut ever since the committee’s last meeting, when the FOMC chose not to cut just yet, but to “wait and see.” During his recent appearances before the House and Senate, Chair Powell only seemed to reinforce the general belief that “wait and see” meant “we’ll cut in July.” Finally, since the relatively dovish Jim Bullard, the lone dissenter in June, who favored a rate cut then, still thinks that a 25 basis point cut should suffice, it hardly seems likely that the Fed will cut its target by more than that amount. In short, it’s no surprise that futures traders now see a quarter-point cut as all but certain.

But it doesn’t follow that next week’s FOMC decision will be altogether free of suspense. On the contrary: there’s still a big question-mark hanging over it. The question isn’t whether the Fed will lower its rate target, and by how much. It’s whether market rates will respond in kind.

IOER: From Leaky to Lacking Gravity

Under normal circumstances, short-term market rates follow, or even anticipate, Fed rate changes as a matter of course. Certainly that was so before the Fed started paying interest on banks’ excess reserve balances (IOER) in October 2008, thereby switching from its former, asymmetric “corridor-type” operating framework to its current “floor” framework. And, allowing for the “leakiness” of the Fed’s IOER floor, which caused the effective fed funds rate and some other money-market rates to post below the IOER rate, that pattern continued to hold until several years ago.

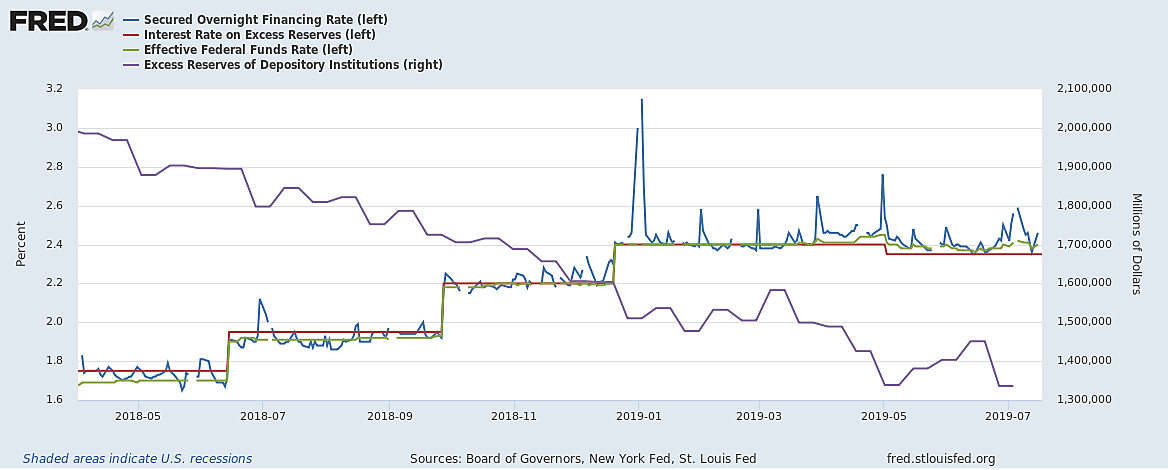

But, as I explained in a previous post, in recent years market rates have stopped moving in step with the Fed’s IOER rate settings. Instead, with every rate change since 2015, the gap between the IOER rate and short-term market rates has also changed. Between 2015 and 2019 what had been a positive gap gradually disappeared; and since early 2019 (as the chart below shows) the gap has turned negative.

Although various reasons have been offered for this change, the most straightforward one attributes it to the Fed’s balance-sheet unwind. That unwind, which began in October 2017 and is scheduled to end sometime after this September, is said to have reduced banks’ excess reserve holdings (the chart’s purple line and right scale) enough to make it necessary once again for some banks to borrow fed funds to avoid reserve shortages. That this should be happening with some $1.3 trillion of excess reserves still at banks’ disposal may seem implausible. But between them, Basel’s LCR requirements, Fed supervisors’ reported (but officially unacknowledged) insistence that banks meet part of those requirements using excess reserves, and the very uneven distribution of outstanding excess reserves among banks, seem capable of accounting for occasional reserve shortages.

So far, the Fed has responded to the tendency of market rates to rise relative to the IOER rate by putting space between the upper limit of its fed funds rate “target range” and its IOER rate. While these were once identical, three “technical adjustments” have now put a 15 basis-point gap between them. The Fed has thus been able to avoid missing its (increasingly wide) target. But that purely cosmetic victory shouldn’t deceive anyone: the plain truth is that it’s the proximity of market rates to the IOER rate that matters: changes in the IOER rate are supposed to lead to sympathetic changes in other market rates, and thence to changes in the extent of lending and investment. If market rates don’t keep step with the IOER rate, monetary policy isn’t working properly. And if they don’t budge when the IOER rate changes, monetary policy isn’t working at all.

Stuck in Neutral?

And to judge by the last IOER rate change, monetary policy may not be working at all. As the chart below shows, that last 5‑point IOER rate cut (the slight drop in the red line toward the right-side of the chart) took place at the end of April. Because the cut was made without changing the Fed’s target settings, it was billed, not as an official rate cut, but as the latest of the Fed’s “technical adjustments.” Nevertheless, from a strictly economic perspective, it was a rate cut in every sense that matters, because, as I noted a moment ago, changes in the Fed’s upper- and lower- target range settings are merely cosmetic, whereas changes in the IOER rate are supposed to do the actual, heavy lifting of influencing other market rates. (A second administered Fed rate — offered by its Overnight Reverse Repurchase facility— both defines the lower limit of its rate target range and limits the extent to which the fed funds rate can fall below the IOER rate. But that facility has seen very little activity since overnight market rates rose to, and then beyond, the IOER rate.)

So, just how much heavy lifting did April’s IOER rate cut do? The answer, as the chart shows, is: next to none. Although the effective fed funds rate (green line) did decline for a while, it only touched down on the lowered IOER rate twice, and briefly. As of mid-July it was back at 2.4 percent, that is, precisely five points above the new IOER rate, where it had been for most of the period preceding the April change. In short, to judge by the effective fed funds rate, the April IOER cut ended up doing precisely nothing.

Yet bad as that sounds, it understates things. Since the Fed introduced its floor system, the federal funds market has been notoriously thin, making the effective fed funds rate an unreliable proxy for the general level of short-term market rates, and of overnight market rates especially. A better proxy, available since mid-2018, is the New York Fed’s “Secured Overnight Financing Rate” or SOFR, “a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight collateralized by Treasury securities.” As the chart shows, the SOFR (blue line) also declined for a time after the April IOER cut; but recently, at 2.46 percent, it’s higher than it was at the time of the cut; and at one point is was just shy of 2.6 percent! I suppose that some people can look at this record yet remain convinced that a rate cut next week is bound to be fully effective. But I’m not one of them.

Fixing A Broken Fed

Instead, I’m an incurable pessimist. Consequently I will be sitting at the edge of my seat, and biting my nails, not before but for some days after the FOMC’s announcement, with my eyes glued to the SOFR and other overnight rates, to see whether they fall below their almost constant average levels so far this year, and do so by the amount of the Fed’s cut. If they don’t, the good news is that we can all stop worrying about the Fed’s future rate decisions. The bad news is that we’ll have to start worrying about how to fix an apparently broken Fed.

How to do that? There are two obvious options. But one of them isn’t tweaking the Fed’s target range settings yet again. To repeat (for it seems to bear repeating), those rate limit settings are cosmetic only, like so much lipstick; and pretending to fix a broken Fed’s rate-control system by messing with them is like putting lipstick on a pig. The Fed may claim that the lipstick is helping it to hit its rate target. But it cannot claim that it’s actions are moving market rates as they’re supposed to.

The first option is for the Fed to suspend its balance-sheet unwind at once, instead of waiting until October, and if needed to reverse course by resorting to enough Quantitative Easing to keep overnight rates no higher than the IOER rate. The second is to establish a Standing Repo Facility (SRF) like the one proposed in March by Jane Ihrig and David Andolfatto. By standing ready to trade reserves for banks’ holdings of Treasury securities at a rate set only slightly higher than the IOER rate, the SRF would put a ceiling on overnight market rates, keeping them close to the IOER rate, much as the Fed’s ON-RRP facility once limited the extent to which those rates could fall below the IOER rate. In the limit, as the distance between the STP and ON-RRP rates approached zero, the Fed would exercise perfect control over overnight repo rates by entirely displacing the private overnight repo market! According to recent reports, informed by the FOMC’s June proceedings, the Fed is now leaning toward the SRF solution.

If the Fed does go the SRF route, it needn’t stop shrinking its balance sheet. On the contrary: the Fed may find it desirable to unwind more aggressively: knowing that they can trade government securities for reserves in a pinch, and provided regulators let them, banks that now have plenty of excess reserves will be inclined to swap them for higher-yielding Treasurys. Reserves will then become less scarce, while Treasurys will be in relatively high demand. By selling more Treasurys to meet that demand, the Fed can help prop-up the far end of a troublesomely inverted yield curve.

The Corridor Option

Fed officials might be happy not to go even that far, sticking instead with their current plan to cease unwinding sometime soon after September. Personally I think they ought to go further, taking advantage of the new SRF to switch from the present floor system to an orthodox corridor system. In a corridor system a single Fed “deposit rate” would be offered to all institutions that keep balances with the Fed, directly or by means of an reverse repo facility. That rate would define the lower limit of the corridor, while the proposed SRF, or something like it, would define the upper limit. Reserves would be kept scarce enough to keep the effective fed funds rate between, and ideally half-way between, the corridor limits. Just how low the quantity of excess reserves would have to go to achieve this outcome, given present regulations (but taking the presence of an SRF into account) is hard to say; but it’s likely to be less, and perhaps much less, than half their present amount.

Why prefer a corridor? First, the smaller Fed balance sheet it entails means a correspondingly reduced Fed “footprint” on the U.S. credit market: the Fed could once again claim, as it did not long before the Great Financial Crisis, to “Structure its portfolio and undertake its activities so as to minimize their effect on relative asset values and credit allocation within the private sector.” By doing so the Fed would leave the task of credit allocation, and the risks it entails, as completely to private-sector intermediaries as possible. Doing that makes sense, surely, as efficient credit allocation is neither part of the Fed’s mandate nor something that it’s able to engage in, given the (quite proper) restrictions on assets it’s allowed to acquire. As Charles Plosser has eloquently argued, a small Fed balance sheet would also limit “the opportunity and incentive for political actors to exploit the Fed’s balance sheet to conduct off-budget fiscal policy and credit allocation.”

Switching to a corridor system would also serve to revive the presently moribund fed funds market, by once again confronting banks with occasional reserve shortages. By so doing it will supply a powerful incentive both for the building of durable interbank credit relations based on routine bank cross monitoring — monitoring that keeps banks alert to other banks’ condition. Such interbank credit relations and monitoring can play an important role in limiting systemic risk, by reducing sound banks’ exposure to panic-based runs while enhancing their access to last-minute private-market funding, ultimately limiting the need for Fed bailouts.