The Federal Reserve used to focus on holding down “core” personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation. The median FOMC projection of core PCE inflation at the June meeting was 4.3% for this year, for example. But the last three reports were well below the FOMC’s expected norm for 2022. Core PCE prices rose at an annual rate of only 3% in February, 3.3% in March and 3.4% in April.

A comparable core PCE figure for May will not be out until June 30. But impatient Fed officials have moved on to new games with new and mysterious rules –such as “find and seek the Quixotic neutral rate.”

Meanwhile, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has been busily changing the subject and hiding or moving the goal posts.

The Wall Street Journal reports, “While the Fed typically pays greater attention to core prices, which exclude volatile food and energy prices, Mr. Powell has said the central bank must place more focus for now on overall inflation [he explicitly mentioned ‘spikes in commodity prices’] because of concerns that consumers and businesses are anticipating price pressures to continue. Fed officials believe expectations of future inflation can be self-fulfilling. If those expectations are rising, the Fed could be required to lift rates to levels that push even harder on the monetary brakes.”

Raising central bank interest rates in response to spikes in commodity prices is certainly not a new idea. As I recently documented, every recession since 1957 was preceded by a dangerous mix of rising oil prices and a rising federal fund rate. Few economists believe oil price spikes alone would have sufficed to knock down the agile U.S. economy; the Fed’s assistance was required.

Always ready to help, the Fed Chairman is now redefining what he might be willing to consider as unmistakable evidence of slowing inflation. Such evidence apparently now excludes any good news from Core PCE inflation in favor of “spikes in commodity prices.” Such spikes are, he acknowledges, “beyond our control” yet they somehow justify all interest rates hikes. Why? Because they might affect expectations about future inflation.

So, there it is. The target seems to have shifted, for the moment, from actual core PCE inflation to estimates of expected future inflation.

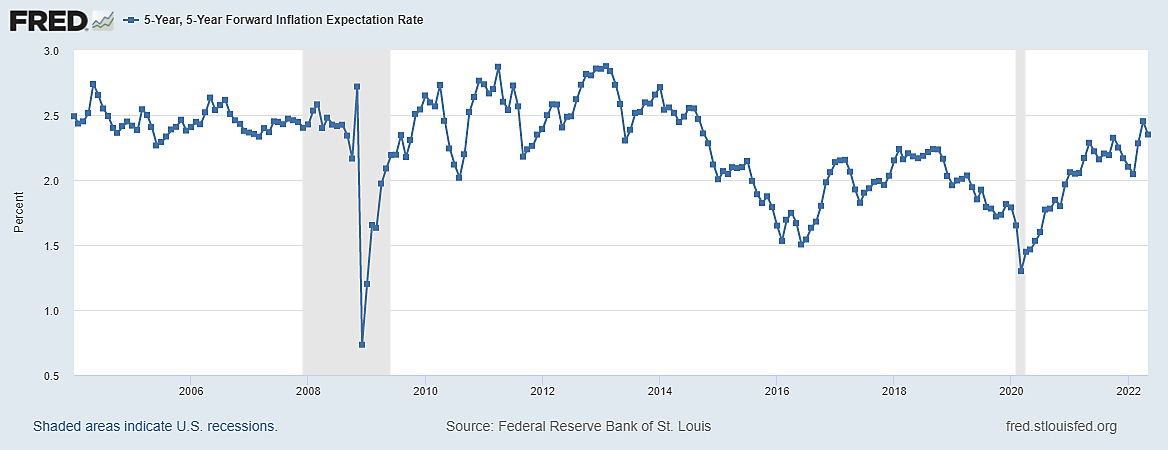

But why? Expected inflation does not cause or predict actual future inflation, nor does it explain past inflation. To see why, look first at the Cleveland Fed’s sophisticated estimate of the inflation estimated five years ahead. Recent 5‑year expectations have not yet reached 2.5% inflation. And the estimates are so obviously cyclical that they have no predictive value at all. If rising oil prices and interest rates create yet another recession as in 2007-09, then expected inflation will indeed fall amazingly fast until the recession is over but no longer.

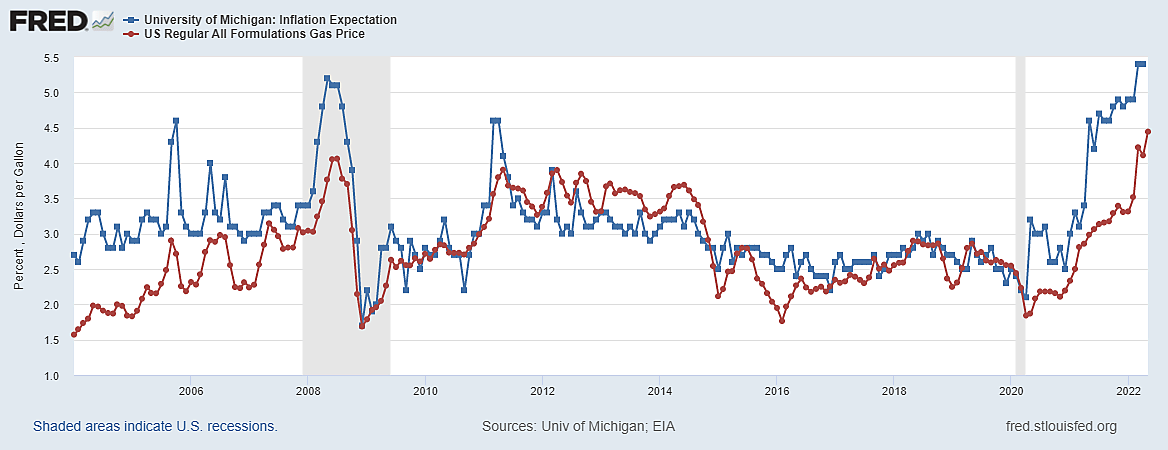

The second graph shows the University of Michigan monthly survey of expected inflation one year ahead. How much inflation people expect a year from now depends on what they have recently read in newspaper headlines or experienced at the supermarket or gas station. In fact, as the red line shows, next year’s expected inflation clearly rises and falls with today’s price of gasoline.

Another good reason to discard these inflation expectations surveys as a rationale for so-called “above neutral” fed funds rate schemes is that linking interest rates to gasoline prices can be highly inflammable.