The last Federal Open Market Committee meeting projected PCE inflation to slow to 2.1% by the end of 2025. Yet 2.1% turned out to be the actual average inflation rate in the second half of 2022.

Rather than applaud that performance, Chairman Powell and other Fed officials have been changing the subject —away from prices toward wages, and to a suspicious subset of prices that excludes all good news about prices of goods and energy and future rent data in favor of “core services less housing.”

“Fed Chair Jerome Powell and several colleagues shifted attention recently toward a narrower subset of labor intensive services by excluding prices for food, energy, shelter and goods. Mr. Powell has said prices in this category, which rose 4% in December from a year earlier [emphasis added], offer the best gauge of higher wage costs passing through to consumer prices.”

Many medical, information and business services rely heavily on technology. Transportation and delivery services obviously rely on fuel. But Chairman Powell uses a stereotype of “services” to mean local labor-intensive services such as restaurants, hair salons, dry cleaning and motels which are largely immune from foreign competition.

The Wall Street Journal reporter Nick Timiraos, who covers the Federal Reserve, explained the latest Fed narrative in his recent article, “Fed Debates Whether Wages or Low Unemployment Will Drive Inflation.”

“Stubbornly high inflation is finally easing,” he writes (as if six months of low inflation is a modest surprise), yet “Federal Reserve officials have voiced unease that prices could reaccelerate because labor markets are so tight…” “Officials worry tight labor markets could allow paychecks to rise in lockstep with prices, as occurred during the 1970s… If wages continue to grow at their recent rate of 5% to 5.5%, that would keep inflation well above the Fed’s 2% inflation goal, assuming productivity grows around 1% to 1.5% a year… If wage growth slipped to 4%, getting inflation to 2% would be easier.”

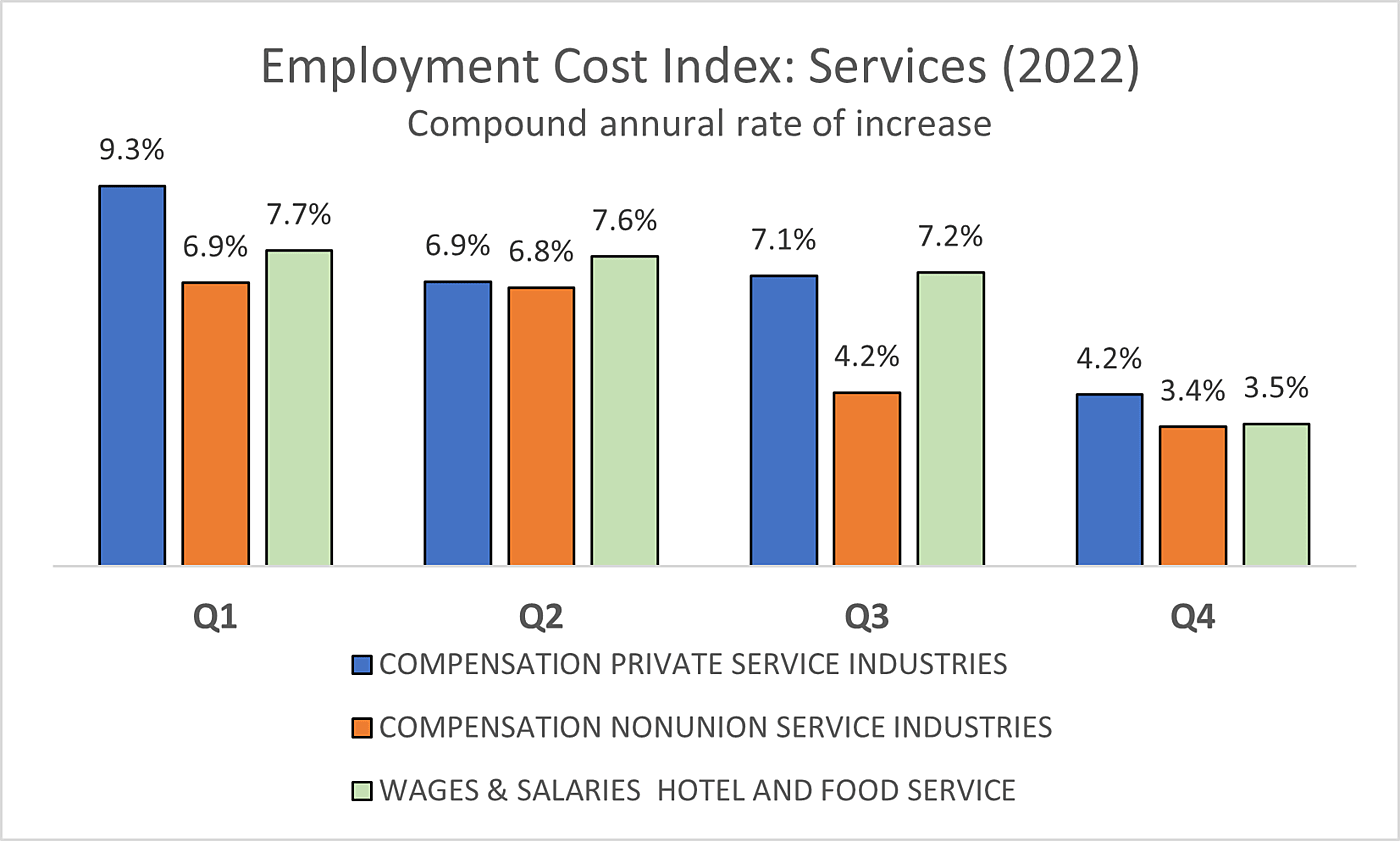

Fortunately, the quarterly Employment Cost Index just came out before the FOMC meeting concluded and it shows compensation (wages and benefits) rising at a 4.2% rate in the fourth quarter —down significantly from 4.8% in the third and 6.5% in the second.

What about allegedly inflationary compensation in service industries, which the Chairman and others have been worrying about?

The graph shows the fourth quarters’ annual rate of compensation growth for services was the same as for the private sector a whole (4.2%), and a little slower (3.5%) for nonunion services. Only wage and salary figures are available for accommodations and food service industries, but they too rose at a 3.4% pace.

The “tight labor market” theory of service prices is no substitute for simply including those prices in the measuring of inflation, which the PCE and CPI indexes do.

Diverting attention away from an actual and impressive 6‑month decline in actual price inflation toward a theoretical conjecture about possible future wage-push inflation in a subset of local service prices is an unhelpful distraction at best. Growth of service industry wages and benefits (like inflation in general) has been slowing down rather than speeding up.