[Author’s note: as I composed this essay, unbeknownst to me, some clever devil in the Trump administration thought it wise to change the geographic designations of President Trump’s current nominees to the Fed’s Board of Governors. Thus Judy Shelton, who in the January 16th nomination announcement was designated “of Virginia,” is now described as being “of California,” while Chris Waller, listed then as “of Missouri,” is now “of Minnesota.” Because Shelton was in fact born in California, her nomination now appears in conformity with long-standing practice as described in my article. The only basis I’m aware of for Chris Waller’s Minnesota designation is that he earned his B.S. at Bemidji State U.]

Although one might suppose that, to be eligible to serve as a Federal Reserve governor, a candidate should know something about monetary policy or banking or both, so far as the law is concerned, only two things clearly matter: a candidate cannot serve more than once, and he or she can’t be from just anywhere.

Few Americans will know that that second requirement exists, why it does, and how it has come to be routinely ignored. Yet the question of geographic eligibility is likely to be raised during upcoming Senate confirmation hearings for two current Fed Board nominees, Judy Shelton and Chris Waller. Hence this brief “Fed Geography Lesson,” written for the sake of those who, should a fuss be raised about where a nominee comes from, wonder what it’s all about.

Checking Eastern Influence

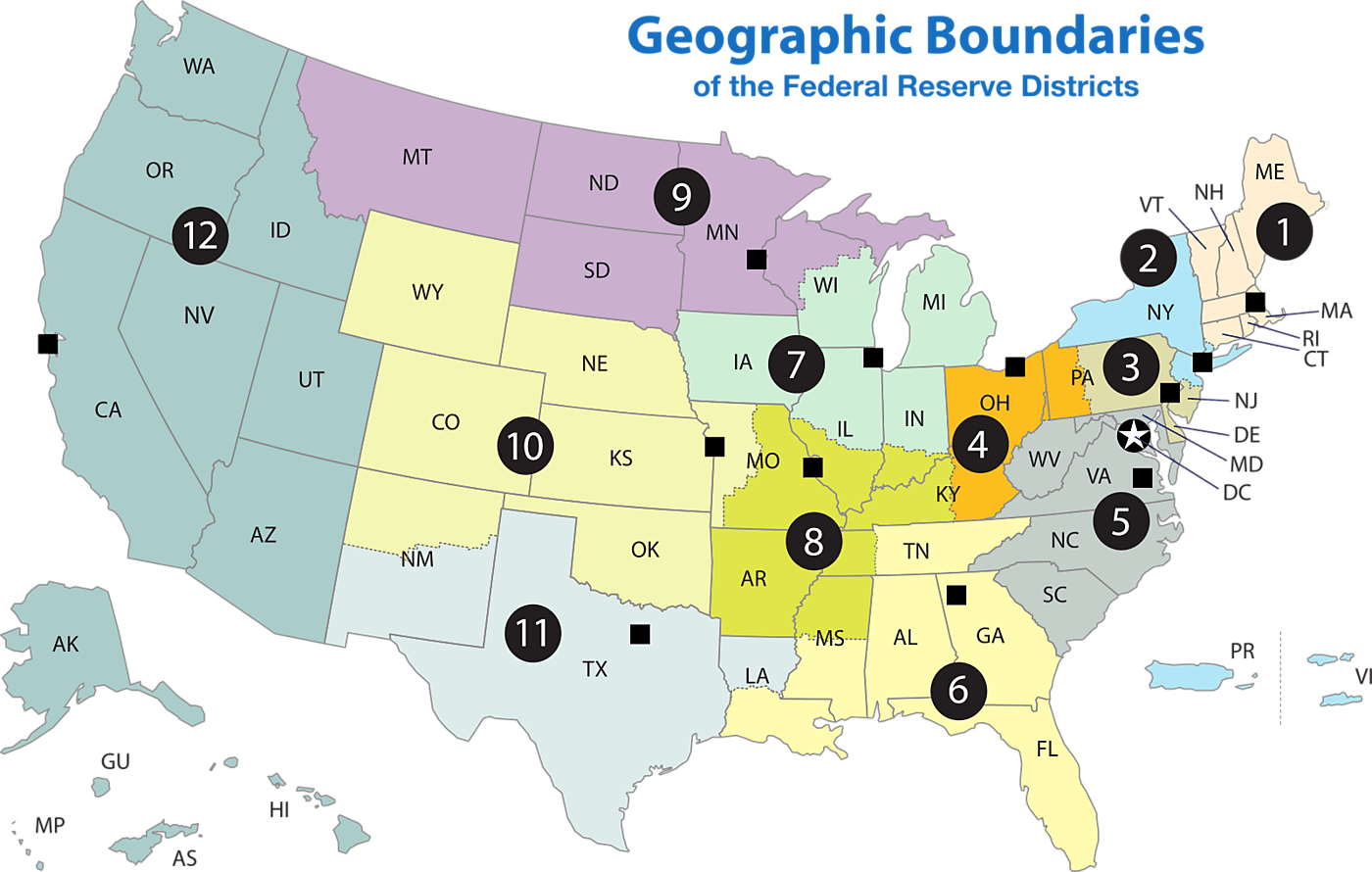

Unlike other central banking arrangements, the Federal Reserve System consists, not of a single central bank, but of a dozen banks each responsible for a separate territory or district. The system is overseen by a Board of Governors headquartered in Washington, D.C., whose seven members are appointed by the President for terms lasting up to 14 years.

When, in 1913, the Federal Reserve Act was being hammered-out in Congress, certain influential Democratic Congressmen, fearing that the Federal Reserve Board (as the present Board of Governors was then known) might come to be dominated by persons (and Wall Street bankers and their cronies especially) from the East Coast, took preventative action: they had the Act’s 10th Section stipulate, first, that no more than one member of the Board should be from any one Federal Reserve district; and second, that in nominating Board members the President “shall have due regard to a fair representation of the financial, agricultural, industrial, and commercial interests, and geographical divisions, of the country.”

From Obscurity to Controversy: The Case of Peter Diamond

For most of the Fed’s existence, the Federal Reserve Act’s geographical diversity provisions drew little public attention. But in 2011 they became front-page news when Richard Shelby (R‑AL), then ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee, appealed to them, and to the first provision especially, in successfully opposing Nobel Laureate Peter Diamond’s appointment to the Board. Although Diamond was supposed to represent the Chicago Fed district, he had only tenuous ties to it, whereas he’d long resided in Boston, a district that was already being represented at the time by Daniel Tarullo.

Some commentators, including the CMFA’s own Mark Calabria, defended Shelby’s stand, holding it to mark a needed return to strict adherence to the law and to the intentions of the Federal Reserve’s founders. Others, however, including Diamond himself, saw it as mere cover for a strictly partisan act, namely, Republican retaliation for Democrat Senators’ having blocked Randall Kroszner’s Board reappointment several years before.

In truth, both interpretations were valid.

Today, Judy Shelton’s nomination has raised the geographic diversity question again. According to some of Shelton’s critics, including Sam Bell of Employ America, being “of Virginia” (according to the official nomination papers), Shelton is only qualified to represent the Richmond Fed district. But that district is already represented by Governor Lael Brainard. Like Shelby, Shelton’s critics have the law on their side; and, like him, they are, one strongly suspects, only inclined to insist upon it because they hope it might disqualify a nominee they oppose for other, including partisan, reasons.

A Sea Change

When, and how, did the Fed’s geographic diversity requirement devolve into a weapon of party politics? Clark Hildabrand, a lawyer who was then completing his J.D. at Yale, where he studied with Cato adjunct scholar Jonathan Macey, answered that question very thoroughly in a 2016 note for the Yale Law & Policy Review. I draw heavily upon that work here.

Early in his note, Hildabrand observes that, of the Federal Reserve Act’s two provisions aimed at achieving a geographically-diverse Board, only the first, providing that no two of the Board’s members be from the same Federal Reserve district, is specific enough to have real teeth. Yet, even it allowed for more than one interpretation of what being “from” a particular Fed district meant. The deliberations that gave shape to the Act’s final draft suggest that “from” was originally understood to refer to where a prospective appointee lived at the time of his or (eventually) her nomination. Still, it was not long before

Presidents, intent on nominating individuals with similar political values, close personal ties, or recognized expertise, began to bend the requirements… away from the focus on residency… and toward inclusion of where the nominee was born.

Allowing for this particular bending of the rule, the diversity provision was abided by until 1978. In that year, what Hildabrand calls a “sea change” came about with President Carter’s nomination of G. William Miller to represent the Fed’s 12th (San Francisco) District. Although Miller got his law degree from Berkeley, he was born in Kansas City and had been living in Boston for two decades. But both the Boston and Kansas City Fed districts were already represented on the Board, while the San Francisco spot was open. Carter therefore asked the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) whether his choice of Miller was consistent with the statute. In its response, the OLC opined only that Miller did not have to be born in and reside in the Fed District he was appointed to represent. He was qualified, in other words, to represent either the Kansas City or the Boston district.

That finding did not, of course, mean that Miller could legally represent the 12th (San Francisco) District! Still, his nomination went forward. When questioned about his West-Coast ties, Miller said he understood “that an opinion has been given by the Attorney General’s Office that an adequate relationship exists in order for me to be a representative of that district.” Miller had either been misled himself or was misleading his interrogators. Still, the Senate took him at his word, paving the way, Hildabrand says, “to even lesser Senate enforcement of the geographic diversity requirements.”

Miller’s case was soon followed by others like it. In 1979, for example, Emmett Rice was appointed to represent the 2nd (New York) Fed district despite being a long-time resident of Washington, D.C. who was born in South Carolina; and in 1980 Lyle Gramley, who also lived in Washington and was born in Illinois, was chosen to represent the Kansas City district. Gramley’s case provoked objections by several Senators, including Jake Garn (R‑Utah), the Senate Banking Committee’s ranking minority member. According to that Committee’s report on Gramley’s nomination, the Senators complained

that in recent years strict attention has not been given to the representation requirements in the Federal Reserve Act. …In several cases individual Governors represented regions in which they have not lived for some time or in which they have spent only a small portion of their lives.

The committee nonetheless overwhelmingly recommended that Gramley be confirmed, with only two Senators dissenting. Senator Garn was among those who supported him, but only because he thought “it would be unfair to penalize Dr. Gramley” after he’d supported others concerning whom the same objections might have been raised. Garn nonetheless made it clear nevertheless that in future he’d “oppose otherwise qualified nominees unless they honestly met the Federal Reserve Act’s geographical and other diversity requirements”; and the committee as a whole resolved “that in the future full consideration will be given to the regional and economic interest requirements specified… in the Federal Reserve Act” and that “regional representation should reflect to the maximum extent possible, a genuine relationship with the Federal Reserve district from which the individual has been nominated.”

Alas, if it was kept at all, the Senate’s resolution wasn’t kept for long. Instead, the Senate was eventually to pay less heed than ever to the Federal Reserve Act’s diversity requirements.

The Floodgate Opens

If in confirming Miller the Senate not only bent but severely twisted the law calling for geographic diversity at the Fed, when it confirmed Susan Bies’s 2001 nomination by President Bush, it went from twisting the law to thumbing its nose at it. Bies was born in New York and resided in Memphis. But because those places were in already-represented Fed districts, President Bush nominated her to represent the 7th (Chicago) Fed District, where she’d earned her graduate degree and worked briefly at the Chicago Fed. So far, the case resembles Miller’s. But Bies’s case differed in that Bies was generally recognized, in official documents and throughout the hearings, as being “of Tennessee.” That is, the Senate did not consider her to be “of” the district she was nominated to represent. Yet no Senator objected to her appointment on that score.

From this point until Peter Diamond’s 2010 nomination, the Fed’s geographic diversity requirement appeared to be a dead letter. According to Hildabrand, out of sixteen Fed Board members confirmed by the Senate between 2001 and 2016, nine were officially held to be “of” Fed districts other than those they were meant to represent. These were:

- Susan Bies, 2001: “of Tennessee,” but to represent the Chicago Fed district;

- Ben Bernanke, 2002: “of New Jersey,” but to represent the Atlanta Fed district;

- Donald Kohn, 2002: “of Virginia,” but to represent the Chicago Fed district;

- Ben Bernanke, 2006: “of New Jersey,” but to represent the Atlanta Fed district;

- Randall Kroszner, 2006: “of New Jersey,” but to represent the Richmond Fed district;

- Frederic Mishkin, 2006: “of New York,” but to represent the Boston Fed district;

- Elizabeth Duke, 2008: “of Virginia,” but to represent the Philadelphia Fed district;

- Jerome Powell, 2012: “of Maryland,” but to represent the Philadelphia Fed district; and

- Jeremy Stein, 2012: “of Massachusetts,” but to represent the Chicago Fed district.

Hildabrand notes that, in three of these instances (Bernanke 2002 and 2006 and Stein 2012), the nominees were in fact born in the Fed districts they were slated to represent. So they might have met the diversity requirement by being considered “of” their birth states. Still, the fact that the Senate didn’t bother to consider them so, yet did not hesitate to confirm them, speaks to the degree to which the diversity requirement had ceased to matter: even when a relatively easy way to meet it was at hand, no one bothered to use it.

The Charade Continues

Since Hildabrand wrote, and notwithstanding Shelby’s highly-publicized appeal to the diversity requirement in opposing Peter Diamond’s confirmation, the Senate has continued to do little more than pay lip service to that requirement. Although Randy Quarles was born in San Francisco and lived in Utah (which is also part of the San Francisco Fed district) when he was being considered in 2017 for the post of Fed vice chair of bank supervision, when it came to being nominated he allowed himself to be represented as being “of Colorado,” which is in the Kansas City Fed district, thus avoiding a clash with Janet Yellen, who already represented the San Francisco district.

And consider the case of Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida, who was appointed in 2018. Clarida was born in Illinois and lived in New York, but was designated “of Connecticut,” to qualify him for the 1st (Boston) Federal Reserve district, which unlike Illinois and New York was as yet unrepresented. But Clarida’s only substantial connection to Connecticut consisted of his having been a managing director at PIMCO, which is located in Southport, CT, in Fairfield County. And it happens that, although most of Connecticut falls within the Boston Fed district, Fairfield County belongs to the New York Fed, which Powell already represented. Never mind: so far as the record reveals, no Senator bothered to ask Mr. Clarida which part of Connecticut he was “of.”

In short, although they did not do so for most of the Fed’s existence, for the last two decades, Senators have routinely turned a blind eye to the Federal Reserve Act’s geographic diversity requirement. The Peter Diamond case was exceptional. And, should any Senator oppose Judy Shelton’s on geographic grounds, that, too, will be exceptional.

It may also prove awkward, for Christopher Waller, President Trump’s other nominee. Waller is a far less controversial candidate than Shelton. But he was born in Nebraska and both lives in and has been designated as being “of” Missouri—two states already represented by sitting Fed governors. In short, geographically speaking, he and Shelton are in precisely the same boat. That should make it awkward for anyone to oppose one on geographic diversity grounds without opposing both. But, partisan politics being what they are, no one should be surprised to see the attempt made.

Ties That Bind

If the Fed’s geographic diversity requirements have ceased to be meaningful except as a (very blunt) weapon of partisan politics, perhaps we’d be better off without them.

Perhaps. But the requirements’ original purpose—making sure the Fed didn’t become a plaything of East Coast banking interests—shouldn’t be forgotten. In fact, as Hildabrand documents, the requirements’ neglect has gone hand-in-hand with a dramatic change in the actual geographic composition of Fed appointees. For example, while only 30 percent of Fed Board members appointed between 1914 and 1996 were born on the East Coast, 80 percent of those appointed between 1996 and 2015 were born there, and that despite a considerable, concurrent decline in the East Coast’s share of total U.S. population. This bias, it bears noting, is only compounded by Wall Street’s outsize influence upon the regional Fed banks. In an age that prizes diversity while worrying about Wall Street’s capturing of those meant to regulate it, this makes for very bad optics, if nothing worse; and one very much suspects that, were the matter to be put to a referendum, the Federal Reserve Act’s geographic requirements would remain on the books.

But having geography matter on paper is one thing; making it matter in practice, not just occasionally, but consistently, is another. Doing so means making the statute tamper-proof, or at least a lot more tamper-resistant. That shouldn’t be hard: as Hildabrand notes, it could be accomplished by amending the Fed’s geographic diversity provision so as to have it specify that a candidate’s geographic origin be determined by his or her residence as reported to the IRS, or (alternatively) by where he or she has been registered to vote in the years leading to the candidate’s initial nomination.

On the other hand, legislators should keep in mind that geographic diversity is but one of many sorts of diversity one might wish to see exhibited by the Fed’s governing body. It happens to have been a form of diversity Congress considered especially important in 1913. But today there are other diversity goals for which arguments have been offered, including having the board include at least one community banker, more women and minorities, or fewer PhDs. To pile-on diversity objectives is to limit the pool of prospective governors having other desirable qualifications, such as familiarity with various non-financial industries, or being a good communicator. It’s possible, in other words, to go too far in mandating Fed Board diversity, geographic or otherwise. So Congress must decide, again, what sort of diversity it cares about most.

In the meantime, should any Senators choose to play the geography card during the coming confirmation hearings, we should allow that they’ll have the spirit, if not the letter, of the law on their side. But let no one suppose that, in playing that card, they aren’t also playing politics.