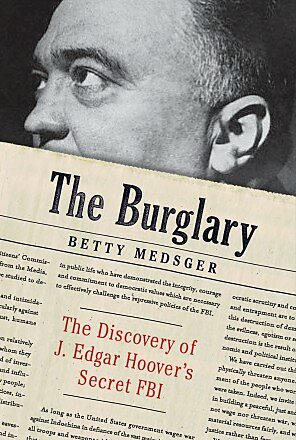

This Thursday at Cato, we’re hosting an event for a remarkable new book: Betty Medsger’s The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI (RSVP here). As I explain in the Washington Examiner today, it’s a story as riveting as any heist film, and far more significant:

Forty-three years ago last Saturday, an unlikely band of antiwar activists calling themselves “The Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI” broke into a Bureau branch office in Media, Pennsylvania, making off with reams of classified documents. Despite a manhunt involving 200 agents at its peak, the burglars were never caught, but the files they mailed to selected journalists proved that the agency was waging a secret, unconstitutional war against American citizens.

As a young Washington Post reporter, Medsger was the first to receive and publish selections from the files—over the protests of then-attorney general (and later Watergate felon) John Mitchell, who called the Post three times falsely claiming that publication would jeopardize national security and threaten agents’ lives.

Four decades later, those claims echo in former NSA head Michael Hayden’s assertion that the US is “infinitely weaker” because of Snowden’s leaks. Like the apocryphal old saw suggests, if history doesn’t repeat itself, at least it rhymes.

“As if arranged by the gods of irony,” Medsger writes, the very morning Hoover learned of the break-in, then-assistant attorney general William H. Rehnquist (later Chief Justice), in testimony the FBI had helped prepare, told a Senate subcommittee that what little surveillance the government engaged in did not have a “chilling effect” on constitutional rights. Among the first documents Medsger reported weeks later, was a memo urging agents to “enhance the paranoia… get the point across there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox.”

Ironies abound. The burglars timed the heist for March 8, 1971, when the country would be distracted by the “Fight of the Century” between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Medsger notes the “poetic justice” that the much-spied upon Ali would unwittingly help provide cover for exposure of FBI spying. Oddly, it’s acting attorney general Robert Bork–survivor of the “Saturday Night Massacre” and nobody’s idea of a civil libertarian)–who orders the release of key documents on the COINTELPRO program and urged the incoming attorney general to investigate the program. There’s another vignette where President Nixon speaks to an FBI Academy graduating class about “reestablishing respect for the law”–and the next evening orders Haldeman to have someone break into the Brookings Institution and steal a purloined copy of the Pentagon Papers (a zealous Chuck Colson suggested firebombing the think tank to create a distraction).

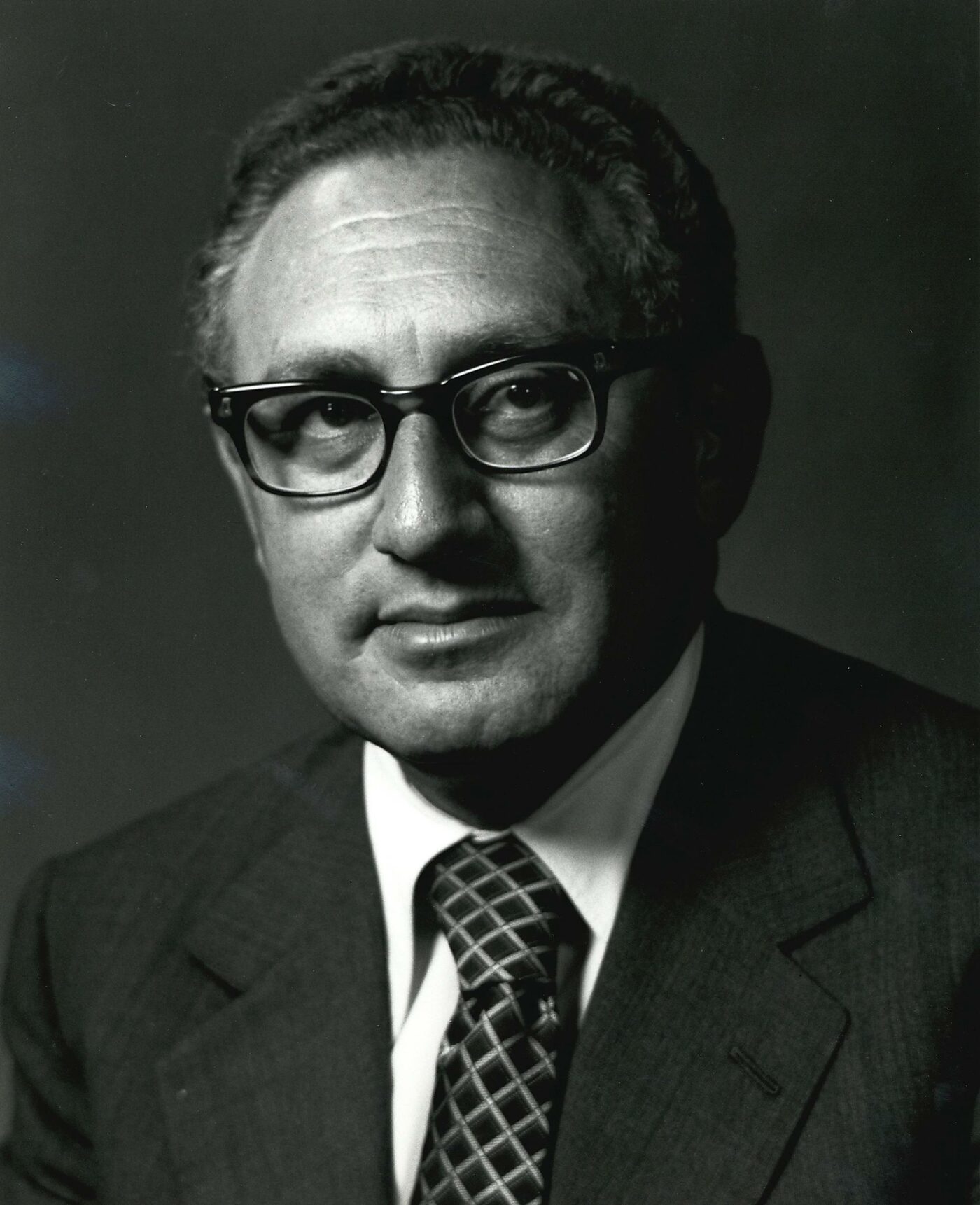

The book is full of “truth is stranger” moments: if a historical novelist made up a scenario where, two days before the burglary, the ringleader, Haverford physics professor William Davidon, goes to the White House for

a sit-down with Henry Kissinger to argue about the Vietnam War (thanks, ultimately, to an introduction made by Shirley MacLaine), there’s no way I’d have bought it. Stranger still, at the time, Davidon was an unindicted co-conspirator in a bogus kidnapping case engineered by Hoover in which Catholic peace activists had supposedly plotted to hold Kissinger hostage. Kissinger didn’t take it very seriously, having joked to the press that the plot had been engineered by “three sex-starved nuns.” As the meeting began, Medsger reports, “Kissinger immediately turned to Sister Beverly, sitting on his other side, and apologized for his flippant ‘sex-starved nuns’ comment.”

Last week, an indignant Rep. Mike Pompeo (R.-KA) chastised the organizers of Austin’s South by Southwest conference for inviting Edward Snowden to address the group via video feed: Snowden is “a traitor and a common criminal,” he railed, “whose only apparent qualification is a willingness to steal from his own government.” As I’ve said before, the debate over the content of Snowden’s character is a sideshow: what’s important is what he revealed: secret, unlawful surveillance capabilities that J. Edgar Hoover could hardly have imagined 40+ years ago. Unless we’ve made radical improvements in human nature in the interim, those capabilities–and the temptations they represent–should concern us greatly.

The legacy of the Citizens’ Commission shows that their “willingness to steal from their own government” may have been the only way to stop much greater lawlessness. Here’s what the FBI’s own website says about the burglars:

A radical group called “Citizens’ Committee to Investigate the FBI” broke into the office in Media and stole a wide array of domestic security documents that had not been properly secured. Some of the documents mentioned “Cointelpro”, or Counterintelligence Programs—a series of programs aimed to disrupt some of the more radical groups of the 1950s and 1960s. The leaking of those documents to the news media and politicians and the subsequent criticism, both inside and outside the Bureau, led to a significant reevaluation of FBI domestic security policy.

Medsger quotes Neil Welch, one of the few top agents within the Bureau to oppose COINTELPRO at the time:

“If [the burglars] had been convicted, I would have recommended that they should be given suspended sentences because of the major contribution they made to their country.”