The comparison has by now been made so often that it may qualify as a platitude. I mean that between stablecoin issuers and “wildcat” banks, the fly-by-night scams that supposedly flooded the antebellum United States with notes nominally worth some stated amount of gold or silver, but actually worth little more than the rag paper they were made of.

Such disreputable stuff, we keep hearing, is what “private” currency always tends to be like. The paper sort survived until federal authorities nationalized the nation’s paper money during the Civil War. And (we are told), digital currency will be just as bad, unless the Feds take control of it as well.

In his recent contribution to your favorite online source for insightful money and banking commentary, Larry White has already explained how stablecoins differ from old-fashioned banknotes, wildcat or otherwise, and not just because they’re digital. And different stablecoins operate very differently. For these reasons, it’s unwise to draw conclusions about stablecoins from past experience with banknotes.

But as I plan to show here, it’s also unwise to generalize about privately-issued banknotes; and no generalization could be more misleading than the claim that “wildcat” banknotes were typical of the lot. In truth, wildcat banks were far from common even in the antebellum United States. And history offers many examples of commercial banknotes that were literally “as good as gold.”

Stablecoins and Wildcats

That there were such things as reliable and safe banknotes is something you’d never guess from the sort of rhetoric Larry and I are complaining about. Senator Elizabeth Warren recently offered a typical specimen, while questioning Lev Menand during Senate Banking Committee’s June 9th hearing on digital currencies,

This is not the first time [she said] that we’ve had private-sector alternatives to the dollar. In fact I’m going to go back further than you did. In the 19th century, “wildcat notes” were issued by banks without any underlying assets. And eventually, the banks that issued these notes failed and public confidence in the banking system was undermined. The federal government stepped in, taxed these notes out of existence and developed a national currency instead. And that’s why we’ve had the stability of a national currency.

Writing in The Wall Street Journal two weeks earlier, James Mackintosh called stablecoins “the living embodiment of free banking,” which he described in turn as “the system of lightly-regulated and often fraudulent issuers of dollar bank notes that dominate U.S. finance until the government stepped in after the Civil War” (my emphasis). Drawing on Joshua Greenberg’s recently-published Bank Notes and Shinplasters, Mackintosh told of how antebellum banks “would fool auditors by shipping the same chest of coins from one [bank] to the next to be counted multiple times, or by topping up a barrel of nails with a layer of silver.”[1]

A few days before Mackintosh’s article appeared, Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard spoke at the Consensus by CoinDesk Conference here in DC. Governor Brainard also chose to “harken back to that period, the free banking era, in U.S. history,” to make a case against stablecoins and for Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). “The inefficiency, the fraud, the instability in the payments system that was associated with active competition among issuers of private paper banknotes,” she said, “led to what eventually was a uniform form of money backed by the national government.” Far from considering that remote experience of only limited relevance to the choice today between private and public digital currency, Brainard insisted that it should be “a prominent consideration.”

Taken together, these comparisons of stablecoins with antebellum banknotes suggest that U.S. banks were lightly regulated; that many if not most were wildcats; and that their notes were often worth far less than their face value. They also suggest that the Federal government stepped in during the Civil War to rid the nation of discounted currency, and that the new currency it put in their place was both innately uniform and more stable.

And hardly a word of it is true.

The Myth of “Free” Banking

The claim that antebellum U.S. banks were mostly wildcats may well be the hoariest of all myths of U.S. monetary history. Nor is the claim that antebellum banks were “lightly regulated” much better. Economic historians, myself among them, have been trying to bury these myths for decades. But they keep getting dredged-up again, usually to justify some bad policy.

The myth that antebellum banks were “lightly regulated” appears to rest on two indisputable facts. The first is that the Federal government was out of the banking picture between the demise of the second Bank of the United States, in 1836, and the Civil War. The second is that, during this period, several states, starting with Michigan in 1837, passed so-called “Free Banking” laws.

Purveyors of the “lightly regulated” myth seem to think that banks established under Free Banking laws were “free” not just in name but in fact, that is, that they were subject to neither Federal nor state-government regulation. They also seem to believe that most state banks were, or eventually became, “free” banks. Add to these beliefs enough tales of dross-filled barrels topped-off with silver, and one can hardly resist concluding that, because they were hardly regulated, most antebellum banks were outright frauds.

Yet the conclusion is wrong because it rests on faulty premises. No adjective, first of all, could be less suitable than “light” for describing that state of bank regulation on the eve of the “Free Banking” era. Instead, as Bray Hammond observes in his monumental, Pulitzer-prize winning study of antebellum banking, “the issue was between prohibition and state control, with no thought of free enterprise.” In the Western territories banking was simply illegal, while in many frontier states only one or two banks were tolerated. Only the Northeast saw anything approaching open competition, and even there every new bank had to be approved separately by a state legislature that was likely to have been encouraged by ample bribes.

“Free Banking” laws, establishing general bank incorporation procedures, were a response to the often corrupt “charter” systems. In states with such laws, banks could be established by any person or group that satisfied certain requirements. But while entry was thus eased, those requirements were usually far from trivial. “Free” banks were all subject, on paper at least, to minimum capital requirements, regular reporting requirements and inspections, and (in many instances) specie reserve requirements.

Two requirements to which all free banks were subject deserve particular attention. First, branching was strictly forbidden: every free bank was a “unit” bank. Second, free banks had to secure their notes with specific collateral, usually consisting of various state and federal government bonds, as well as some railroad bonds. The collateral had to be surrendered to state authorities before the banks opened, so that, if any failed, it might be sold off, and the proceeds employed to pay off noteholders. That, at least, was the theory. Unfortunately, as we’ll see, things didn’t always work out that way in practice.

So “free” banks weren’t free to do whatever they liked. But even if they had been, antebellum banking as a whole wouldn’t have been “lightly” regulated, because most antebellum banks weren’t “free.” Only 18 of the 34 states established before the Civil War embraced Free Banking at one time or another, with Michigan doing so twice. And in some of these few, if any, free banks were ever actually established—a fact that’s itself at odds with the claim that such banks were always lightly regulated. Chartered banks, in the meantime, continued to exist and to be established alongside “free” ones. In all, of some 2,450 state banks established between 1790 and the start of the passage of the National Currency Act in 1863, only 872, or a little over a third, were even nominally “free.”

Rare Beasts

That most antebellum banks weren’t “free” itself means that most weren’t wildcats, for all authorities agree that wildcat banking only occurred where Free Banking laws were in effect. But wildcats were rare even in those places. Outside of the (Old) West, it was entirely unknown, and in the West itself it wasn’t all that common.

Economists and historians have used several criteria to distinguish wildcats from legitimate banks, including how long they lasted (usually a year or less), how many notes they issued relative to their capital (many), how much holders of their notes managed to recover when they failed (no more than 95 cents on the dollar, and often much less), how much specie they kept on hand (not much), and how many people lived where they ostensibly did business (typically, no more than a few hundred). Because different scholars have emphasized different criteria, careful estimates put the total number of wildcats as low as several dozen and no higher than 173, with no more than 90 or so ever present during any one year.[2]

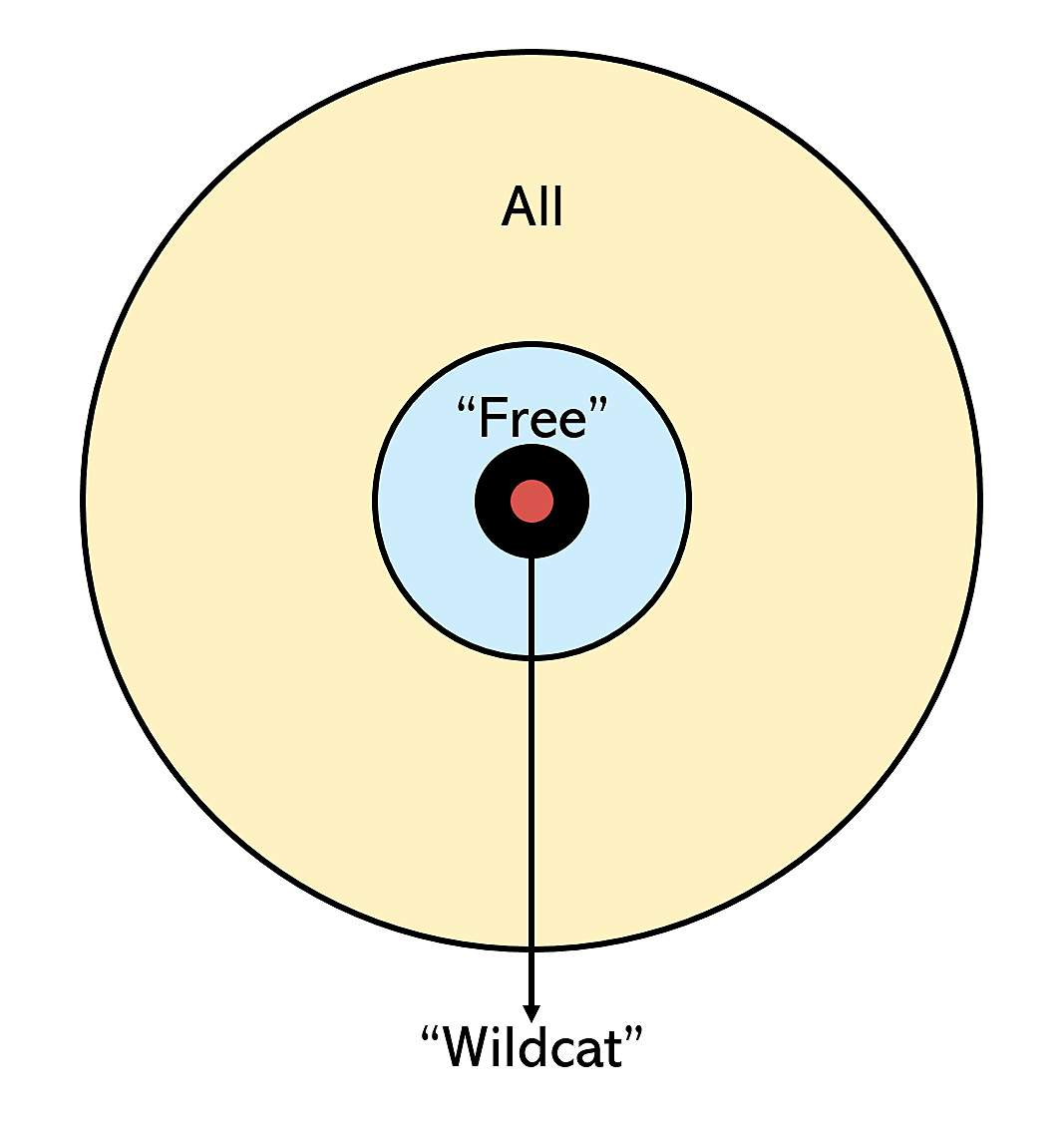

A Venn diagram, with concentric circles of different sizes standing for the relative numbers of different sorts of antebellum banks, and the thick boundary of the innermost circle standing for the wide range of wildcat bank estimates, helps to put the numbers into perspective. It’s a diagram I wish every critic of stablecoins would consult before waxing eloquent about how the United States once found itself drowning in worthless banknotes.

Breeding Bad

So there weren’t many wildcats. But there were certainly some; and that there were any compels us to ask why.

That the bad apples were vastly outnumbered by legitimate banks, and that they flourished in no more than five states—Michigan, Minnesota, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Illinois—and often only briefly, suggests that, far from illustrating the inevitable consequences of allowing private firms to supply currency, they were products of peculiar circumstances.

The record bears this out. Take the case of Michigan. The first state to pass what it called a “general banking” law, it also experienced the first, and by all accounts the worst, outbreak of wildcat banking. The stories about kegs of nails and glass masquerading as specie, and of strongboxes full of real specie being rushed from bank to bank one step ahead of the inspectors, all come from it, courtesy of Alpheus Felch, Michigan’s governor from 1846 to 1847, and its bank commissioner from 1838 to 1839, when the wildcatting took place.

Just about everything that could possibly have gone wrong with Michigan’s free banking law did, starting with its timing. The law, passed by an overwhelming majority (Felch was one of only four representatives who dissented), took effect on March 15th, 1837. Less than two months later, on May 10th, the Panic of 1837 struck, causing New York’s banks to suspend payments. Soon banks were suspending all over the country. On June 22nd, Michigan passed emergency legislation allowing its banks to suspend payments until May 16th, 1838.

Although 14 banks were doing business in Michigan at the time of the suspension, they were all chartered banks: no free banks had yet been set up. And that might have been the end of that, had the June 22nd legislation not extended the privilege of suspending payments to any free banks set up before it expired! So it happened that brand new banks—banks that had yet to prove themselves capable of keeping a promise—were allowed to go into business, and to take full advantage of the government’s assurance that their notes were adequately secured, without having to fear being put to any test for the better part of a year. “What a temptation was this,” Felch later recalled, “for the unscrupulous speculator. We can hardly be surprised at the scenes which followed, and which marked the period as a most wonderful epoch in financial history.”

Having rolled a red carpet out to shady bankers, Michigan tried to make up for it by assigning Felch and two other newly-appointed bank commissioners the Herculean task of inspecting all the banks in the state at least once every three months. It was these commissioners who found themselves chasing after boxes of gold, the mere possession of which, together with an oath sworn by a bank’s directors, sufficed to meet the law’s capital and specie requirements.

The commissioners were quickly overwhelmed by a “fearful amount of fraud and perjury,” for before a year had passed, 40 new banks sprang into being. Though these collectively swore to a nominal capital of almost $4 million, little of that was ever actually paid in. Many did business, or pretended to, from remote places—if not where wildcats literally roamed. And almost all failed in short order. Finally, commencing April 16th, 1839, the government closed the door to new free banks. Come December, only four were left. Thanks to the shoddy collateral with which those banks were allowed to secure their notes, including over-appraised farm mortgages and personal bonds, the public, apart of course from the bankers themselves, ended up at least a million dollars poorer.[3]

The Best, and the Rest

So Michigan’s experience was indeed disastrous. But nothing could be more mistaken than to suppose that the faults of its first free banking law (for it would try again, in 1857) were faults of U.S. style “free banking” per se, let alone of any and all private currencies. Even Alpheus Felch, who opposed Michigan’s arrangement from the start, and who witnessed its utter failure, knew better. Even its badly flawed general banking law, he observed in 1878,

was not without some good features, but it came into existence at a most unfortunate time, and the keenness and unscrupulousness of desperate men, taking advantage of its weak points and corruptly violating its salutary provisions, used it to public injury.

The proof of Felch’s opinion consists of the numerous instances, including Michigan’s own when it tried Free Banking for a second time, in 1857, in which more carefully designed and thoroughly enforced Free Banking laws were quite successful. New York’s Free Banking system, launched not long after Michigan’s, was among the success stories. Though it got off to a rough start, with several free banks failing in 1842, and those caught holding their notes incurring large losses, losses fell steadily after that. During the 1850s, the overall loss rate on notes issued by New York’s free banks was less than 0.1 percent. By the 1860s it had become negligible.

Wildcat banking was unheard of in New York, as it was in most states with Free Banking laws. The sole exceptions, apart from Michigan, were Wisconsin, Indiana, Minnesota, and Illinois; and whether wildcats were important in any of them is controversial. According to most economic historians, including Gerald Dwyer,

There is no evidence that free banks in these states generally were characterized by continuing fraud to transfer wealth from passive noteholders to shrewd bankers. There also is little evidence supporting a generalization that these free banks were imprudent, let alone financially reckless.

Although free banks in these and other states failed, and did so more often than chartered banks, misconduct usually had nothing to do with it. Instead, Dwyer continues,

banks’ losses occurred sporadically when developments outside the banking systems decreased the demand for the banks’ notes or decreased the value of the banks’ securities.

The failure of several dozen Wisconsin free banks in 1861, for example, appears to have been entirely due to their investment in Southern-state bonds. Because those bonds traded at or above par before the threat of secession loomed, it’s absurd to suggest that these banks issued notes “without any underlying asset.” Still, the bonds lost much of their value once hostilities began, leaving their holders with heavy losses.

Illinois: Fraud or Force Majeure?

Admittedly, the line separating wildcats from honest banks that ran into hard times could be very fine. Consider the case of Illinois. Its original free banking law was far from perfect, and more than a few “banks” that did little but issue notes were among the 145 firms established under it by 1861. Still, most authorities agree with Francis Phillippi, the author of an 1896 thesis on the history of banking in Illinois, that up to then

This system worked well…so far as the security for the circulation was concerned. Fourteen banks had gone out of existence, and had had their affairs wound up before 1861. All their notes redeemed without loss to the holders except in one case a loss of three percent was sustained.

Even in that unique case, noteholders ultimately received 88 cents on the dollar. This record was especially remarkable in light of the severe panic that swept through the country in 1857, putting paid to many banks elsewhere. In fact, Phillippi says, the Illinois free banks proved themselves so well that they “afterwards enjoyed increased confidence” in the stability of their currency.

Yet, paradoxically, the 1857 Panic also appears to have contributed to the system’s ultimate, spectacular failure. As Dan Du explains, having first forced many Eastern banks to suspend specie payments, that event subsequently “drained specie from Illinois owing to a lack of commerce.” A poor 1858 crop only made matters worse. During that year alone, Illinois banks’ specie holdings declined 63 percent. By May, those outside of Chicago had also stopped paying specie on demand. Yet because they were considered more than adequately secured, their notes stayed current throughout the state, satisfying a genuine need. Had it not been for those notes, Du observes, not only ordinary payments but “everything in the way of settlement of domestic balances and local improvement must have come to a dead halt.”

The demand for suspended banknotes, and the profits banks could make by satisfying it, were so great in fact that 81 new free banks were established between 1858 and 1861, 66 of them in 1860 alone. By October of that year, the banks had issued over $11 million in notes on specie reserves of less than $303,000. But those notes were amply secured by over $12 million in state government bonds held by state authorities.

Or so it seemed. The hitch was that, of those $12 million in bonds, over $9.5 million were from states that eventually joined the Confederacy. Illinois’s free banks thus suffered the same fate as Wisconsin’s: as the threat of secession grew, the backing for their notes shrank. On the eve of the Battle of Fort Sumter, most Southern-state bonds were worth about half their par value. Within a year, 90 banks closed their doors; and this time holders of their notes lost millions.

Were the failed Illinois banks “wildcats”? According to Rolnick and Weber, they weren’t: they were simply victims of force majeure, having never intended to defraud anyone. But Du disagrees. They were wildcats, he says, because, besides having never been prepared to redeem their notes on demand in specie, many didn’t even have a discernible place of business. Nor did they make any loans, their profits having instead consisted entirely of interest drawn on the bonds securing their notes. “People needed the currency they produced at a time when money was scarce,” Du says. “So the community acquiesced in their conduct.”

But, the debate continues, if the public “acquiesced,” in what sense can the banks be said to have bamboozled it? Would having no banknotes at all to trade with really have been better than having to rely on suspended ones?

It may never be possible to answer such questions decisively. But what can be said is that, even by the most generous reckoning, wildcat banking was exceptional.

Those Banknote Discounts

If wildcat banks were rare in the antebellum United States, the same can’t be said of banknote discounts, meaning notes’ tendency to trade at less than their face values except in their home markets. That antebellum notes were often discounted is itself sometimes taken to mean that wildcat banking was rampant. And even those who know better sometimes treat such discounting as an inherent shortcoming of privately-supplied currency. Thus Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey, speaking at Brookings last September, worried that in the absence of adequate government oversight of private currencies we might witness “a return to the literal wild-west in which individual banks issued their own private currencies, which were worth different amounts depending on recipient’s assessment of the soundness of the issuing bank” (my emphasis).

In truth, antebellum banknote discounts were for the most part neither a consequence of the lack of regulation nor a reflection of distrust of their issuers. Default risk was sometimes a factor, to be sure. But when it was, shopkeepers and banks tended to refuse them altogether, leaving it to professional note “brokers” to deal with them, much as they dealt with notes of banks that were known to be “broken,” but which might yet have some liquidation value. Discounts on “bankable” notes, on the other hand, reflected nothing more than the cost of sorting and returning them to their sources for payment in specie, plus that of bringing the specie home. This explains why, whatever the discounts placed on them elsewhere, most notes traded at par in their home markets.

Thanks to the combination of a large country, poor (though rapidly improving) transportation infrastructure, and unit banking, when notes traveled any substantial distance from their source, getting them redeemed could be quite costly. In smaller nations, and especially those, like Scotland, where banks were allowed to branch nationwide, banknote discounts were unknown: the fact that there were many different banks of issue, with varying assets, didn’t prevent such nations from having “uniform” banknote currencies. Even Canada, which was geographically as large as the United States, but much less populous and with a far less developed internal transportation system, managed (with the help of several private clearinghouses) to achieve a uniform currency, based on the notes of several dozen commercial banks, by the early 1890s.[4]

Had it not been for unit banking, the United States might well have had a uniform state banknote currency before the Civil War, thanks to its by then impressive railroad network. Even with unit banking, it came a lot closer than most people realize. Despite already having had over a hundred banks of issue at the time, with hardly any branches, New England managed, with the help of the Suffolk System—an early, Boston-based banknote clearinghouse—to achieve a uniform currency as early as 1824.

By the early 1860s, the rest of the country had nearly caught up to New England. To prove the point, some years ago I asked what loss someone living in October 1863, would have suffered had he or she purchased every non-Confederate banknote circulating at the time for its declared value, and then sold the lot to a New York or Chicago note broker for the broker’s advertised price. To allow for a maximum loss, I considered any note the brokers listed as “doubtful” to be worthless. Even so, the total loss in either market amounted to less than one percent of the investment.

Achieving “A Uniform Form of Money”

The low levels to which banknote discounts had fallen by 1863 ought to make anyone wonder why a government locked in a mortal conflict would bother to overhaul the nation’s currency system just for the sake of getting rid of them. And one has only to consider the components of that overhaul to appreciate its other motives. These consisted, first, of U.S. Notes or “greenbacks,” first issued by the Treasury in 1862; second, of national banknotes issued by new, federally-chartered banks per the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864; and, third, a 10 percent tax aimed at driving any remaining state banknotes out of circulation, which ultimately took effect in August 1866.[5]

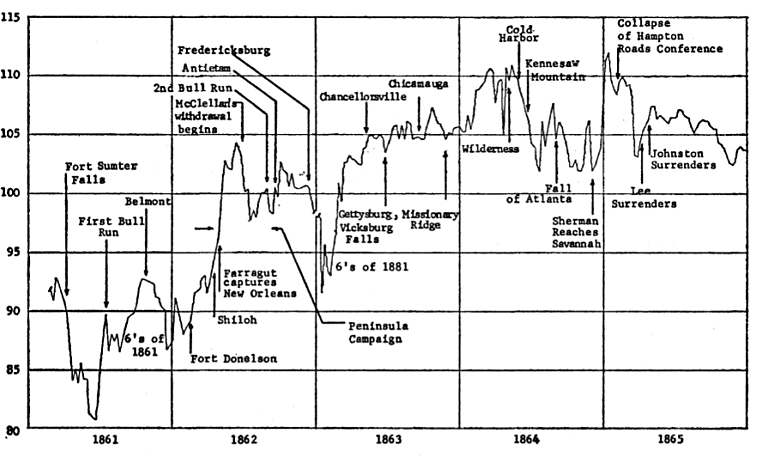

That the overarching, if not the sole, purpose of the greenbacks was to allow the Federal government to pay its bills despite having an “empty purse” is generally recognized. But the National Banking Acts were also meant to replenish the North’s coffers. Like state Free Banking laws, they allowed banks established by them to issue currency only on the condition that it be amply backed by eligible securities. The twist was that the eligible securities were to consist exclusively of bonds issued by (hang on to your hats!) the Federal government! As anyone familiar with the Union Army’s many setbacks during the war will realize, and as a glance at the fluctuating prices of Federal bonds during the conflict (as shown in the image below, taken from Richard Roll’s 1972 article on “Interest Rates and Price Expectations During the Civil War”) makes clear, until the Battle of Gettysburg that choice was no guarantee that national banknotes would be perfectly safe.

Despite this, Federal officials hoped that the mere availability of national bank charters would suffice to persuade state banks to switch to them. In fact, very few did so at first. That posed a problem, not because there wouldn’t be a big enough market for Federal debt—there were plenty of applications for de novo national bank charters—but because creating too many new banks would mean a much more substantial increase in the total currency stock, and, consequently, much higher prices, than the public was likely to tolerate. If there was to be plenty of national currency, there would have to be less state-bank issued currency. Hence the punitive 10 percent tax.

All these measures, you might think, ought to have sufficed to make our currency perfectly uniform. And you’d be right. But chances are you don’t know exactly why they did so. Most people suppose that national banknotes and greenbacks together made up a uniform currency for the simple reason that they were all, directly or indirectly claims against the Federal government. But to think so is to forget the point that a currency’s uniformity isn’t just a function of the “soundness” of its source. As we’ve seen, for redeemable banknotes, which are at least proximately liabilities of the individual banks that issue them, redemption costs also matter.

Although they all bore similar engravings, national banknotes were like state banknotes in being claims against the particular national banks that issued them. And until 1927 national banks were also unit banks. It followed that returning national banknotes to their sources for redemption was costly.

So why, if not for their common backing, weren’t those notes subject to discounts? The answer lies deep within the 1864 National Bank Act, in a little-appreciated paragraph (421, sec. 5196) that begins as follows:

Every national banking association formed or existing under this Title, shall take and receive at par, for any debt or liability to it, any and all notes or bills issued by any lawfully organized national banking association.

Only the national “gold” banks established on the West Coast, where the greenback standard didn’t take hold, were exempted.

Once every national bank was required to accept every other national bank’s notes at par, no one who did business at or near any national bank had reason to value them any less. Thus it was by dint of legislative fiat, and not owing to the superior reliability of national currency, that the federal government achieved a supposedly “more perfect” currency union.

Uniformly Unstable

According to Senator Warren, Civil War reforms didn’t just rid the United States of banknote discounts. They also endowed it with “the stability of a national currency.”

Historians of the Federal Reserve may well wonder just what sort of “stability” Senator Warren has in mind! For had it not been for the notorious instability of the post-Civil War national currency, the Federal Reserve Act might never have been dreamed up. What’s more, much of that instability had its roots in the very Civil War reforms Warren praises.

The national currency’s fundamental shortcoming was its “inelasticity,” that is, its inability to expand and contract according to the public’s currency needs. Hence the Federal Reserve Act’s official title, which begins, “An Act to provide for the establishment of Federal reserve banks, to furnish an elastic currency.”

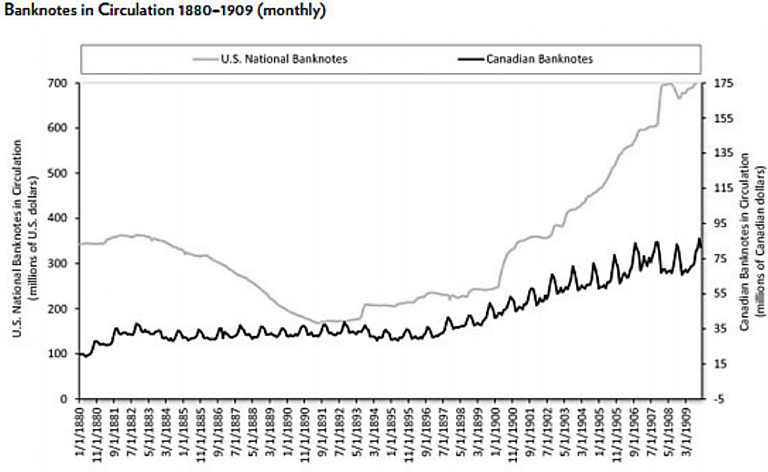

But why was the national currency inelastic? That it wasn’t simply because there was no central bank to manage it is easily shown: one need only consider Canada’s contemporary system, which managed quite well with the same gold-based dollar, but without a central bank or any form of centralized currency arrangement. Canada completely avoided the “currency panics” that rocked the U.S. economy in 1884 and 1893; and it was left unscathed by the still-greater Panic of 1907, which troubled it only for as long as it took Canadian officials to relax a previously-imposed limit on total Canadian bank note issues.

To see just how well Canadian banks, of which there were over three dozen for most of the period in question, managed the currency stock in ordinary times, and how much better they were at it than U.S. national banks, one need only glance at the image below, taken from my 2015 retelling of the story of the Fed’s origins, and consider the need for currency, besides tending to grow over time, spiked with every harvest.

So national currency wasn’t inelastic because commercial banks supplied it. It was inelastic because its quantity was tied to the availability of bonds required to secure it, and because national banks’ inability to discount it prevented them from actively returning notes to their sources. The one regulation limited the maximum quantity of national bank notes banks could issue, and made temporary additions to the quantity unprofitable, while the other meant that the quantity of notes wouldn’t automatically recede once there was less need for them.

For these and other reasons (including the fact that it contributed to the South’s postbellum impoverishment by depriving it of banks and credit), it’s not as obvious as many people suppose that the switch to national currency ultimately did the nation more good than harm. It’s still less obvious that suppressing state bank notes, instead of allowing them to coexist with their national counterparts, was beneficial. For my part, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t.

A Cartoonish Perspective

Canada’s wasn’t the only private currency system that was head and shoulders above any 19th-century U.S. system. The Scottish system was just as noteworthy for its stability as well as its efficiency. Yet Scottish and Canadian banks were in many respects more genuinely “free” than their U.S. counterparts. Until 1845 the Scottish banks were hardly regulated at all, except by Scots contract law. Besides being free to branch nationwide, they weren’t obliged to “secure” their notes with any particular assets, or (prior to 1845) to maintain any particular specie reserves. Entry into Scottish banking was also free for companies whose shareholders accepted unlimited liability: until 1858, the privilege of limited liability was limited to three “chartered” banks only. Indeed, in British as well as the Continental usage, “free banking” and its equivalents (“le banque libre,” “bankfreiheit”) refer to genuinely free banking of the Scottish sort, not the phony antebellum U.S. version.

Besides having been celebrated during their heydays, the Scottish and Canadian systems have gotten plenty of attention in more recent times from various economists and economic historians. Larry White’s study of the Scottish system, Free Banking in Britain, first published in 1984, paved the way for numerous studies of other private currency systems worldwide. Kevin Dowd’s 1992 collection, The Experience of Free Banking, alone contains studies of the Canadian, Australian, Colombian, Irish, Chinese (Fuzhouan), French, Irish, and Swiss episodes.[6]

All of which means that, even if central bankers, politicians, and pundits got their U.S. currency history right, they still wouldn’t be doing justice to the history of “private currency.” To do that, they’d have to consider what transpired elsewhere, including Canada, Scotland, and perhaps some of the 60 other nations that relied on numerous private banks of issue for their currency at some time or another. Then they might appreciate how atypical even the best parts of the fragmented U.S. system was, owing to the debilitating effects of unit banking.

Instead, as things stand, our amateur experts’ understanding of the history of private currency—and it must be said that that of many U.S. academic historians and economists isn’t much better—brings to mind Saul Steinberg’s famous New Yorker cover, depicting the world as seen by people living on 9th Avenue: in the foreground Manhattan looms. Beyond it, across the Hudson, a vague little strip represents “Jersey.” Then comes a dreary plain relieved by a promontory or two: the rest of the United States. Finally, across the wide Pacific, China, Japan, and Russia barely rise above the horizon.

To today’s instant “private currency” experts, wildcat banks dominate history as Manhattan’s skyscrapers dominate Steinberg’s drawing, other antebellum banks are so much insignificant hinterland, and the history of private currencies elsewhere is terra incognita. Like the fabled blind men of Indostan, each of whom thought he understood what an elephant was after touching one small part of it, they imagine they know just how dreadful the record of private currencies was because they’re vaguely acquainted with one of its roughest parts.

***

Speaking at the House of Commons in 1948, Winston Churchill, paraphrasing Santayana, said that “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” Those who compare stablecoin issuers to wildcat banks, to argue for suppressing them, and for having central banks issue digital currency instead, think they’re steering us clear of the fate Churchill warned against. If you ask me, it’s at least as likely that they’re steering us straight into it.

_______________________

[1] See here for some remarks of mine on a talk Mr. Greenberg gave on the subject of antebellum banknotes.

[2] The value of 90 is that of Illinois’ purported wildcats ca. 1860. As we’ll see, some deny that these were wildcats at all. To arrive at the range of estimates of total wildcats all told I’ve drawn on Dove, Pecquet, and Thies (2014), Du (2010), Dwyer (1996), Economopoulus (1988), Jaremski (2010), Rockoff (1985), and Rolnick and Weber (1983).

[3] So according to Felch. In their more recent assessment of the Michigan episode, John A. Dove, Gary M. Pecquet, and Clifford F. Thies claim that, had the Michigan legislature not decided, in 1842, to declare the General Banking Act, and the still outstanding claims against banks established under it, null and void, those loses “might have been only $350,000.” The same authors also claim that there were only twelve Michigan wildcats. But that conclusion depends on their decision to apply the term only to those banks that closed within a year of the start of the wildcat period. The size of the innermost red circle in the Venn diagram above reflects this strict definition.

[4] For more details concerning Canada’s achievement see here.

[5] Many sources assume, incorrectly, that the 10 percent tax was among the measures included in one of the National Banking Acts, whereas in fact it was adopted later, as part of the Revenue Act of 1865.

[6] Although Dowd’s book has been sadly out of print for some time now, I’m pleased to announce that the CMFA plans to publish a new, expanded and revised edition early next year.

[Cross-posted from Alt‑M.org]