Pointing to empty store shelves and rising prices brought about by the current “supply chain crisis,” Sen. Josh Hawley (R‑MO) has introduced legislation that would mandate at least half of the value of goods “critical” to national security be produced in the United States. However, one of the most visible examples of the current “supply chain problem” – empty grocery store shelves and rising food prices – shows why simplistic government localization mandates are no panacea and could, in fact, make things worse.

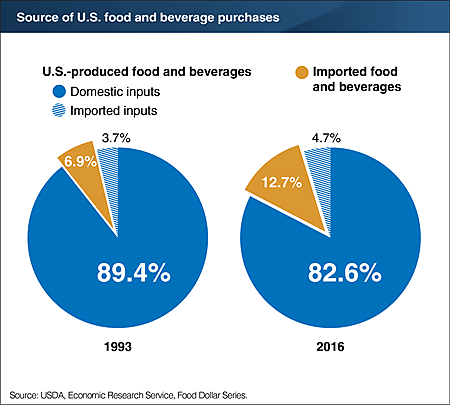

In particular, the vast majority of the food that Americans consume already is produced in the United States. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, for example, more than 80% of Americans’ total food and beverage consumption in 2016 was produced domestically:

More recent data from the USDA show that almost all of our grains, eggs, dairy, and meat are produced here (see Figure 2), yet many of these same products have experienced the highest price increases in recent months.

That a mostly-domestic U.S. food supply chain hasn’t protected American consumers from recent shortages and price increases is unsurprising. For starters, many of the same things that stress global supply chains – COVID-19 outbreaks; supply-demand imbalances; labor shortages in the trucking and warehousing industries; misguided trade, transportation, and immigration policies; etc. – stress domestic ones too. Indeed, one such policy, – the Jones Act, which mandates all shipments between U.S. ports be made on American made, ‑owned, ‑crewed and flagged vessels – might actually burden U.S. supply chains more than their international counterparts, because the law makes coastwise shipping cost-prohibitive and increases pressures on (and prices of) alternative inland transportation. (Ironically, the Jones Act is just the type of local content restriction that Senator Hawley wants to implement for all “critical” goods.)

As we’ve discussed here repeatedly, moreover, supply chain repatriation might insulate the United States from foreign supply or demand shocks but would make us more vulnerable to domestic shocks in the process – a conclusion supported by both academic research and recent pandemic experience in various U.S. manufacturing industries. (See also this U.K. history lesson from Cato’s Ryan Bourne.) Indeed, our mostly-domestic food supply has proven especially vulnerable to local shocks, such as natural disasters. In August 2021, for example, Hurricane Ida forced the temporary closure of major fertilizer chemical plants in southern Louisiana, causing a widespread shortage of fertilizer, spiking prices, and wreaking havoc on farmers in states such as Kansas and Kentucky. One chemical plant remained closed for five weeks. Ida also caused major inland shipping issues, flooding Mississippi River waterways and thus delaying domestic shipments of major crops such as corn and soybeans. Last year, pandemic-related closures of domestic meatpacking plants temporarily reduced U.S. meat production, thus causing the very logistical pressures, supply shortages, and price increases that Senator Hawley’s proposed local content mandate seeks to prevent. And just this week, we’ve learned that dairy prices are facing new pressures because rising labor costs are threatening U.S. dairy production – production, by the way, that has long been subsidized and insulated from foreign competition and just won new protection under President Trump’s NAFTA replacement, the USMCA.

A global pandemic essentially guarantees that supply chains, both global and domestic, will face challenges. But simplistic localization mandates won’t solve these problems and would likely exacerbate them – harming American consumers, manufacturers, and national security in the process.