The Syrian Civil War has produced about 5.8 million Syrians seeking refuge or asylum elsewhere–a scale of population displacement unseen since World War II. Although the flow into Europe dominates the news, most of the registered Syrian refugees remain in the Middle East. Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan are the main recipients of the immigration wave, receiving roughly 1.1 million, 2.7 million, and 640,000 Syrians, respectively. The Gulf States are hosting about 1.2 million Syrians on work visas but they are not legally considered refugees or asylum seekers because those nations are not signatories to the UNHCR commission that created the modern refugee system. Regardless, the humanitarian benefit of Syrians working and residing there is tremendous.

The movement of so many Syrians over such a short period of time should result in significant economic and fiscal effects in their destination countries. Below is a summary of recent economic research on how the Syrians have affected the economies and budgets for Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, and Europe.

Lebanon

Syrian refugees are 24 percent of Lebanon’s population–the highest Syrian refugee to population ratio in the world. However, neither the Lebanese government nor the United Nations has established official refugee camps in the country and registration of new Syrian refugees stopped in May 2015. International NGOs provide humanitarian aid that benefits over 126,000 destitute Syrians, but significant funding shortages have left some Syrians living on less than half a dollar per day. To more efficiently provide aid, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has divided the country into four areas: Mount Lebanon and Beirut, North Lebanon, Bekaa Valley, and South Lebanon. Most refugees have settled in the underdeveloped areas of the Bekaa Valley and North Lebanon because the Lebanese in these areas share many family ties with Syrians. Locals in these areas are struggling to accommodate Syrian refugees despite the family ties.

Many Syrians, especially those with more wealth and greater skills, are responding to the poor economic conditions in North Lebanon and Bekaa by moving to South Lebanon and Beirut where there are more job opportunities, higher wages, cheaper rents, and safer communities. Syrian entrepreneurs are also welcomed in these regions of the country.

Lebanon’s real GDP grew 2.5 percent in 2015, the best growth rate since the turn of the decade, despite losses of investment and tourism due to the Syrian civil war. Furthermore, a World Bank report noted that a 1 percent increase in the population of Syrian refugees increases Lebanese service exports by 1.5 percent, due in part to the so-called market size effect. In the Bekaa Valley and North Lebanon, the influx of Syrians has led to 60 percent reduction in wages because low-skilled Syrian and Lebanese workers are substitutes. Lebanese entrepreneurs are not hiring many Syrian refugees and prefer to blame Syrian-operated businesses for regional economic problems and sluggish growth. The Lebanese government responded in the Bekaa region by closing down Syrian businesses, worsening the employment situation.

In response to the constant inflow of Syrians, the Lebanese government established a new visa system for students, businessmen, and those sponsored by Lebanese citizens. Missing from their visa reforms, however, is a humanitarian visa.

The refugee crisis could have a less negative or maybe even a net-positive effect on Lebanon’s economy after more policy changes. While it is undeniable that wages have fallen in certain areas of Lebanon, there are many Lebanese government policies that have exacerbated that effect. Here are some suggested reforms:

- Immediately grant legal work permits to all Syrian refugees. Most Syrian refugees are informal workers because the government has generally restricted legal work permits. As a result, 92 percent of them do not have a contract and black market employees are especially vulnerable to abuses and wage reductions. If the government allowed Syrians to work legally, they would become more competitive, have more of an incentive to invest in Lebanon-specific human capital, and face an improved bargaining position–all reactions that would help to increase their productivity and likely offset some of the downward pressure on wages.

- Stop restricting Syrian entrepreneurship. Local Lebanese governments, especially in North Lebanon and Bekaa, have limited or shut down Syrian-owned businesses. Syrian entrepreneurship will help alleviate unemployment and wage stagnation problem. The Lebanese government should immediately stop punishing Syrian entrepreneurs.

Jordan

The influx of Syrian refugees into Jordan is equal to about 8 percent of that country’s population. Refugees are not evenly dispersed in Jordan with about 90 percent residing in the governates in the north of the country. Despite the significant population shock, unemployment rates are lower in these governorates than the rest of the country and they have been declining since the start of the Syrian Civil War. On the other hand, labor force participation rates in these governorates are also slightly lower. Overall, Syrian refugees have not had a significant effect on the labor markets in Jordan.

This better labor market outcome could stem from the Jordanian government deregulating the labor market in the face of the refugee surge. Since March 2016, Jordanian authorities have expanded work permit access to refugees using Jordanian Ministry of the Interior identity cards and UNHCR-issued asylum seeker cards, allowing many more Syrian refugees to work in the legal market. About 99 percent of Syrians worked in the underground economy prior to these reforms. This new policy is projected to expand work permit access to 78,000 Syrians in the short term and thousands more in the future. The Jordanian government has a long history of these types of labor laws as their constitution and guest worker laws attest.

These new work permits are better than unlawful employment but they often come with restrictions such as employer sponsorship and minor fees that make them difficult to obtain for some workers. Fortunately, the pace of reform is increasing so hopefully those guest-worker permit barriers are further pared down. Syrian workers who entered the country legally and were not residents of a refugee camp could apply for work permits–a big policy shift for the 83 percent of refugees who are not in camps.

The Jordanian housing market has suffered the greatest shock as rents and prices have climbed in response to the refugees. According to one projection, those rents have grown by 7.73 percent since the beginning of the Syrian crisis–an estimated 5 percentage points higher than if the refugees had not arrived. This effect is unsurprising as the housing market is more affected by immigrant inflows than any other market. Refugees aside, the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring have dampened Jordan’s tourist and trade markets, likely slowing export growth.

The fiscal effects of the Syrian refugee crisis are acute. The Jordanian government supplies a substantial amount of social services and welfare benefits to the Syrians. They consumed an estimated 8.8 percent of the government budget through healthcare, education, and security services. While that number is slightly higher than the Syrian percentage of the population, this estimate was also made in 2014 before the changes in work permit policies.

There are additional policy steps the Jordanian government can take to maximize the benefits from welcoming refugees while minimizing the costs:

- Eliminate or at least reduce fees, remove employer sponsorship requirements, and repeal other restrictions on the granting of work permits to Syrians. By removing restrictions on work permits they can bring Syrians out of the informal market, lower the fiscal costs of supporting the refugees, and allows complementary task specialization to occur in the broader Jordanian labor market.

- Ask the United States to further reduce the trade and regulatory barriers that remain after the passage of the Free Trade Agreement. This will make up for the decline in regional economic activity and provide more employment opportunities in export-oriented industries. If possible, American relaxation of these remaining trade barriers should be accompanied by further Jordanian labor market deregulation and the granting of work permits to all Syrian refugees without fees or restrictions.

Turkey

Turkey is currently hosting 2.7 million Syrian refugees, more than any country in the world. Unlike Jordan and Lebanon, however, Turkey has a much larger population base and a more robust and developed economy. While there are established refugee camps, 85 percent of the Syrian refugees in Turkey have left the camps and found work in the formal and informal markets.

Lower-skilled Syrian workers in the informal market have displaced similarly skilled Turks and increased unemployment in areas where they are concentrated by about 2 percentage points. The government’s restrictive work permit policy likely led to that negative effect. The Turkish government issued regional permits allowing refugees to work only in the refugee community,which concentrated the increase in the supply of labor rather than letting the workers fan out into the Turkish economy. Refugees not employed in the community either had to seek informal employment or rely on state aid. As a result, the government had to spend an additional $5 billion for the refugees.

Since January 2016, Turkey has taken steps to allow Syrians to work legally. Syrian workers are now allowed to comprise a maximum of 10 percent of the employees in any firm and are subject to minimum wage requirements. While the full effects of this new policy have yet to be measured, some Turkish politicians have recognized the economic benefits of Syrian entrepreneurship and a growing labor market. Legalizing Syrian workers will likely ensure the further decline of the informal market, which has shrunk almost 7 percentage points between 2011 and 2014.

Overall, the Syrian refugees have had a modestly positive impact on Turkey’s economy. Turks have responded to the population shock through occupational upgrading, as the expanded consumer base has created new opportunities for higher wage formal jobs.

Turks have also responded to increased labor market competition by seeking skill upgrades to make themselves complementary to the new Syrian workers. The percentage of Turks in higher education increased from 20 percent to 23 percent from 2011 to 2014. School attendance has increased for Turkish women as well, though those effects may have occurred as a result of other changes in government policy. Turks who directly compete with low-skilled Syrians and don’t change occupation do face some job displacement and wage declines, but the average wage increases as they shift to higher wage jobs. Furthermore, as more Syrians participate in the market, consumer prices have dropped an average of 2.5 percent since 2011 because of increased competition at the lower end of the labor market has made goods more affordable for every Turkish consumer.

Turkey has handled the Syrian refugee surge better than any other neighboring country. Endogenous factors such Turkey’s larger population and more developed economy deserve enormous credit, but Turkey’s recent labor market liberalizations also helped. Turkish occupational upgrading, made possible by a larger labor market, is the best possible result. There are some policy changes the Turkish government can make to further increase the benefits and diminish the costs of the Syrian refugee crisis:

- Increase or remove entirely the 10 percent cap on Syrian employment in firms. The Turkish government could phase-out this cap with increases announced months in advance to allow Turks to adjust or shift occupations in response.

- Eliminate the minimum wages for the refugees and normalize wage regulations for all workers, hopefully with fewer restrictions. This will further diminish the size of the informal labor market and draw more lower-skilled Syrians into jobs.

- Turkey should ask the European Union and the United States to further remove trade barriers on Turkish exports. In exchange, Turkey should take further steps to integrate Syrians into their economy, provide universal work permits, and eliminate the two-tiered labor market regulation system. This will make Turkey a more attractive place for Syrian refugees to stay. The first step in this should be the United States dropping its dumping complaints against Turkish steel firms. A growing export sector in the Turkish economy could help absorb many Syrians.

Europe

There have been 972,012 Syrian asylum applications in Europe between April 2011 to February 2016. Sixty-one percent of them are hosted by Serbia, Kosovo, and Germany, while 27 percent are hosted by Sweden, Hungary, Austria, the Netherlands, and Denmark.

European governments have responded to this influx by increasing fiscal expenditures to accommodate the refugees and provide humanitarian assistance. Increased social expenditures are likely to continue even if optimistic estimates find that 10–15 years are necessary before refugees begin to be fiscally positive. For 2015–2016, the European Commission allocated additional funding of 9.2 billion euros in order to address the refugee crisis. The scale of the funding could be decreased and the time until fiscal balance could be diminished drastically through better labor market integration.

Optimistic projections of refugee integration assume they will have a labor force participation rate 5 percent lower than similarly skilled natives. The refugee unemployment rate is currently 30 percent and well above 50 percent for asylum seekers in Germany, Britain, and France. Unemployment for these groups is even higher in non-EU European countries.

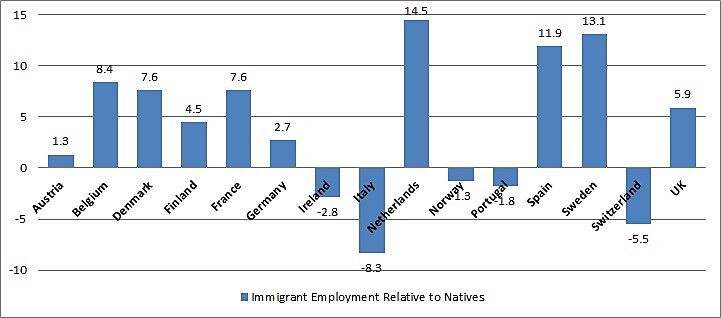

Long-term gaps in immigrant versus native employment vary considerably across European countries (Chart 1). The positive figures in Chart 1 show a gap where immigrant unemployment is greater than native unemployment. The negative figures show when immigrant unemployment is less than it is for natives. There is an especially wide gap in the refugee destinations of Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany.

Chart 1

Long-Term Unemployment Rate Gap between Natives and Immigrants, Aged 15–64 in 2012–2013

Source: OECD http://www.oecd.org/els/mig/Indicators-of-Immigrant-Integration-2015.pdf.

These negative results stem from significant and costly European labor market regulations that prevent non-EU immigrants from economically integrating. The fear of immigrant labor market competition is misplaced as most of them are complementary to European workers, not substitutable. These labor market regulations are even more onerous for Syrians. Labor market policies directly at refugees and asylum seekers are:

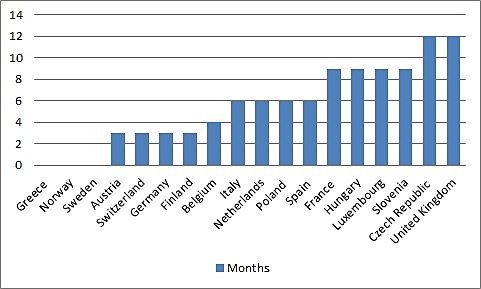

- Work bans. There are significant prohibitions on employment after a refugee or asylum seeker enters a country (Chart 2). These bans make the Syrians completely dependent on charity and government aid while delaying their labor market integration.

- Shortage occupation lists. These lists allow immigrants to be hired to fill the gaps in industries that are supposedly suffering labor shortages. These prevent immigrants from working in many sectors of the economy. Shortage occupation lists in Germany, for example, delay employment even for high-skilled refugees such as university graduates and apprenticeship diploma holders.

- Priority checks. These regulations ensure that businesses guarantee there are no suitable unemployed natives before hiring refugees. The German priority check system places the priority check bar on refugees for 15 months. During this time, if the refugee is interested in a job, the business must ensure not only that no German is qualified to fill this role, but also that no EU citizens of associated countries are qualified and available as well. By placing refugees at the end of the labor line, European nations effectively deny refugees employment options.

- Self-employment bans. These prevent refugees from creating businesses or otherwise employing themselves. In the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, for instance, asylum seekers and refugees are not allowed to start businesses in any case. This is simultaneously harmful to both sides of the labor market, as refugee entrepreneurs would expand European labor demand and help to accommodate fellow refugees as well as European workers.

- Temporary employment bans. These prevent refugees from taking temporary employment. In place in the United Kingdom and Germany, temporary employment bans further limit options for refugees to find work.

Chart 2

Waiting Periods for Asylum Seeker Access to Labor Markets, in Months

Source: OECD http://www.oecd.org/migration/How-will-the-refugee-surge-affect-the-Eur….

Egregious labor policies in the European Union are the roadblock to refugee integration. As such, there are many reforms European nations should undertake to lessen this problem:

- Remove the working bans on new refugees and asylum seekers. Incentivize them to work immediately.

- Remove the other labor market regulations listed above, at least for refugees and asylum seekers.

- Remove minimum wage requirements for the refugees and asylum seekers or give them a temporary reprieve until they gain some labor market experience. Given that a consensus of literature has found minimal effects of low-skill immigration on native wages, the minimum wage only decreases the opportunity for refugees to find work in their host country.

Conclusion

The Middle Eastern countries with substantial Syrian refugees have all responded with similar reforms, to different extents. Turkey and Jordan have done the most to integrate Syrians while Lebanon has done the least. Lessening government barriers to legal employment and entrepreneurship have made the situations better in those destinations. Europe is still struggling, and their sclerotic labor market regulations do not bode well for successful integration unless some serious reforms are undertaken.