“As health concerns for former President Carter mount,” Caleb Brown noted recently in this space, “it’s nice to be able to look back on his time in the White House and see something remarkably positive.” Indeed, our 39th president doesn’t remotely merit the bad rap he gets from conservatives and libertarians. As I wrote a few years back, “at its best, the Carter legacy was one of workaday reforms that made significant improvements in American life: cheaper travel and cheaper goods for the middle class.” For loosening controls on oil, trucking, railroads, and airlines, he should, Daniel Bier suggests, be thought of as “the Great Deregulator.” It’s in no small part thanks to him that conservatives can cry in their microbrews over the sorry state of the 2016 Republican field.

So the man from Plains has a lot to be proud of. In the coming months, I hope he’ll have the consolation of seeing the record corrected and his historical reputation start to rise.

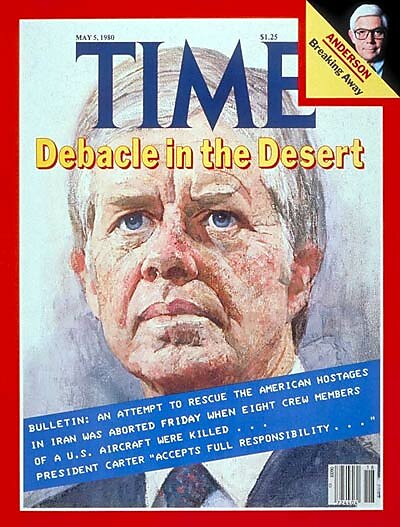

Judging by his recent press conference announcing his illness, however, Carter shares a widely held misconception about where his presidency went wrong. Asked about his regrets, he answered: “I wish I’d sent one more helicopter to get the hostages and we would have rescued them and I would have been re-elected.” Carter was referring to “Operation Eagle Claw,” the aborted Iranian hostage rescue attempt in April 1980. If you’re old enough, you probably remember: the operation never got past the initial “Desert One” rendezvous point, due to the mechanical failure of three helicopters, and eight US soldiers were killed during departure when a helicopter collided with a transport plane.

The botched rescue attempt definitely contributed to Carter’s defeat. But the mission failed during the “easy” part; when you look at what was supposed to come next, it’s hard not to think the whole operation would have been the Bay of Pigs meets Black Hawk Down.

Writing in the Air & Space Power Journal in 2006, war gaming professor Charles Tustin Kamps observed that “the things which did cause the mission to abort were probably merciful compared to the greater catastrophe which might have taken place if the scenario had progressed further than the Desert One rendezvous.” “In the realm of military planning there are plans that might work and plans that won’t work,” Kamps writes, “In the cold light of history it is evident that the plan for Eagle Claw was in the second category.” It would have required “the proverbial seven simultaneous miracles” to succeed.

Here’s what was supposed to happen, per the Eagle Claw factsheet at the Air Force Historical Support Division website:

[Eagle Claw] called for three USAF MC-130s to carry a 118-man assault force from Masirah Island near Oman in the Persian Gulf to a remote spot 200 miles southeast of Tehran, code-named Desert One. Accompanying the MC-130s were three USAF EC-130s which served as fuel transports. The MC-130s planned to rendezvous with eight RH-53D helicopters from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz. After refueling and loading the assault team, the helicopters would fly to a location 65 miles from Tehran, where the assault team would go into hiding. The next night, the team, dependent upon trusted agents, drivers, and translators [provided by the CIA], would be picked up and driven the rest of the way to the embassy compound.

Meanwhile, a separate 13-man team would peel off to attack the Foreign Ministry building and rescue three hostages being held there, as the main Delta group hit the embassy.

After storming the embassy, the team and the freed hostages would rally at either the embassy compound or a nearby soccer stadium to be picked up by the helicopter force. The helicopters would then transport them to Manzariyeh, 35 miles to the south, by that time secured by a team of U.S. Army

Rangers. Once at Manzariyeh USAF C‑141 transports would fly the assault team and hostages out of Iran while the Rangers destroyed the remaining equipment (including the helicopters) and prepared for their own aerial departure. An extremely complex operation, Eagle Claw depended on everything going according to plan. Any deviation could cause the entire operation to unravel with possibly tragic consequences.

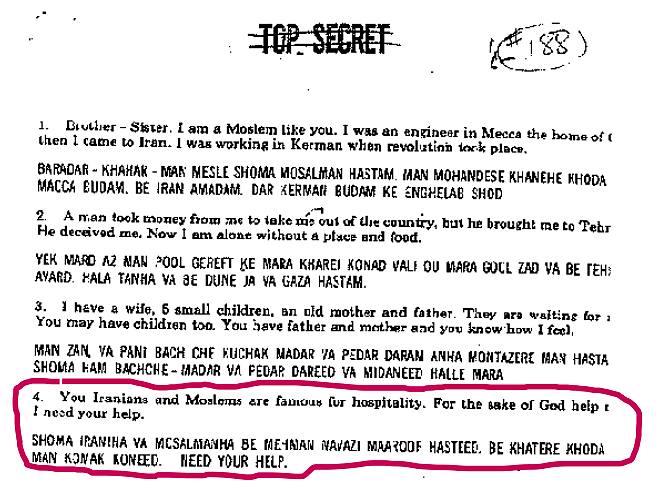

Just in case things didn’t go exactly according to plan, the Delta guys were issued this handy “Farsi Survival Guide” (one page of which is pictured below) to help them bargain and cajole their way out of the country without blowing their cover. For example, they could try something like: “You Iranians and Moslems are famous for hospitality. For the sake of God, I need your help.”

In real life, things started going wrong almost instantly: “Soon after the first MC-130 arrived [at Desert One], … a passenger bus approached on a highway bisecting the landing zone. The advance party was forced to stop the vehicle and detain its 45 passengers. Soon, a fuel truck came down the highway. When it failed to stop, the Americans fired a light anti-tank weapon which set the tanker on fire and lit the surrounding area.”

In a riveting 2006 Atlantic article, “The Desert One Debacle,” Black Hawk Down author Mark Bowden described the resulting chaos: “Suddenly the night desert flashed as bright as daylight and shook with an explosion. In the near distance, a giant ball of flame rose high into the darkness. One of the Rangers had fired an anti-tank weapon at the fleeing truck, which turned out to have been loaded with fuel. It burned like a miniature sun. So much for slipping quietly into Iran.”

Eight copters left the Nimitz; two had to turn back on route due to mechanical problems. Of the remaining six that made it through the vicious sandstorms (or “haboobs”) on the way to Desert One, another arrived with irreparable hydraulic problems. The plan called for a minimum of six helicopters; down to five, on-scene commander Col. Charles Beckwith had little choice but to cancel the mission. As the force began to evacuate, “tragedy struck. One of the helicopters’ rotor blades inadvertently collided with a fuel-laden EC-130. Both aircraft exploded, killing five airmen on the EC-130 and three marines on the RH-53.”

Had Beckwith not hit “abort,” however, it’s easy to imagine that most if not all of the assault force would have been captured or killed and none of the hostages would have made it. Bowden quotes a Delta Force officer who summed it up well: “The only difference between this and the Alamo is that Davy Crockett didn’t have to fight his way in.”

This, to paraphrase Argo, was the worst bad idea we had.

Wait, scratch that: actually, the worst idea was the followup plan developed by the military after the Desert One debacle. According to Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski: “the second plan involved going into the airport at Tehran, taking the airport, shooting up anything in the way, bombing anything that starts interfering, storming the embassy, taking out anybody who’s alive after that process and then going back and taking off.” Except the hostages had been moved out of the embassy after the first failed attempt, and the commandos would have had to try to find them at remote locations. Everybody was supposed to reconvene at the Tehran soccer stadium where a C‑130, jerry-rigged with rockets so it could take off and land like a V‑22 Osprey, would whisk them to safety. You can watch the modified C‑130 crash and burn in a test video here (luckily no one was hurt).

The code name for this scheme? “Honey Badger.” Yes, the second rescue plan took its moniker from the “tenacious small carnivore” identified by the Guinness Book of World Records as “the most fearless animal in the world,” and later the subject of that inescapable 2011 YouTube video—to wit:

“The honey badger don’t care! It’s getting stung like a thousand times. It doesn’t give a [expletive deleted]. It’s just hungry. It doesn’t care about being stung by bees. Nothing can stop the honey badger when it’s hungry. What a crazy [expletive deleted]!”

(Trigger warning: expletives not deleted in viral video link.)

As Michael Crowley noted in a Time article reporting on the scheme, Honey Badger was likely “a last-resort contingency in case Iran began executing the hostages without provocation”–a desperate measure if all else failed. What’s really astounding is that the original plan, Eagle Claw, got the go-ahead in far less desperate circumstances.

Relentless public pressure to “do something!” often leads presidents to do something stupid. The hostage rescue mission was not Jimmy Carter’s finest hour. But it could have been much worse.