President Trump will support legislation to provide legal status to young immigrants who, as he said on Twitter, “have been in the country for many years through no fault of their own—brought in by parents at young age.” The legislation with the most cosponsors in the House and the Senate that would do so is titled the Dream Act. The proposal would help many unauthorized immigrants who deserve help, but for reasons that I cannot explain, the Dream Act prioritizes them above legal immigrant children in virtually the same position who meet all the eligibility criteria.

Most high-skilled immigrants initially enter the United States on temporary H‑1B visas. H‑1B workers can bring with them their spouses and minor children. As I have explained before, H‑1B children live here, attend U.S. schools, grow up and attend U.S. universities, but on their 21st birthday, they lose their legal status, and the law requires them to self-deport if they cannot find another temporary legal status. Most stay at least for a few years longer by switching to a student visa, but this status prohibits work and expires again as soon as they graduate, leaving them in the same position they were before.

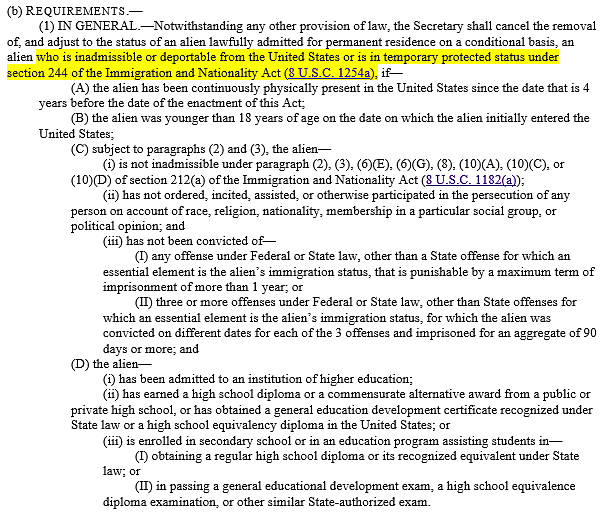

These children were “brought in by their parents” through “no fault of their own” and have “been in the country for many years”—the three criteria that President Trump mentioned for his dreamer legislation, yet the Dream Act, which would provide permanent residency, explicitly excludes them. This is not an oversight. The authors—Senators Graham and Durbin in the Senate—had to write that the law would apply only to a person “who is inadmissible or deportable from the United States” (p. 4) or who is in “temporary protective status,” which is typically given to unauthorized immigrants who can’t be deported due to a crisis in their home country.

In other words, the only way for legal dreamers to obtain status under this bill would be to somehow find a way to violate the law in order to become “deportable.” Even then, the Dream Act makes applicants ineligible if they have violated the rules of a student visa (p. 5), which most legal immigrant dreamers have to switch to when they turn 21 to avoid deportation, unless the Secretary of Homeland Security decides that it is necessary for “humanitarian purposes or family unity” or “otherwise in the public interest” to allow them to apply. Who knows whether he would decide that in any particular case? Few legal immigrants would take the chance that he wouldn’t and risk being deported and banned from the United States for life.

But why is the requirement to violate the law necessary in the first place? What would change if the highlighted of the portion of the bill below was removed? Everyone that the current bill protects would still receive protection. The standards for inclusion would be just as tough. All participants would still have had to reside in the country for 4 years, enter before the age of 18, not have committed any significant crimes, be a high school graduate, etc. So why prioritize unauthorized immigrants over those who are here legally? It creates perverse incentives.

Dream Act Requirements (pp. 4–6)

As I have also explained before, the existence of legal immigrant dreamers is a product of a broken legal immigration system. Current law allows H‑1B employers to sponsor H‑1B workers, their spouses, and minor children for green cards or legal permanent residency. The green card waits for these workers are decades long (see here for a detailed explanation of that problem), so the law also allows H‑1Bs waiting for a green card to extend their status and the status of their spouses and minor children indefinitely while they all wait for green cards. But despite having waited in line for many years, children of H‑1B workers still lose their status as soon as they turn 21. Those who don’t self-deport then become foreign students, which provides temporary status but they cannot work and lose status again as soon as they graduate.

Children of other high-skilled immigrants on less used visa categories—primarily L, O, and E—also face the same problem. The Recognizing America’s Children Act in the House, which some 32 Republicans have signed onto, would allow E‑2 nonimmigrant children to apply for permanent legal status with unauthorized immigrant dreamers but it would exclude all other legal immigrant dreamers (p. 5). That’s better than nothing, but E‑2 nonimmigrant children are only a very small portion of the legal immigrant dreamers. Why would these members open themselves up to prioritizing illegal immigrants over legal immigrants? Many members have explicitly said that they oppose a “special pathway” for illegal immigrants.

It’s not that they want to limit the number of applicants, since both bills dramatically expand eligibility beyond the criteria for the DACA program that President Trump just announced would wind down. DACA protects only unauthorized immigrants who entered under the age of 16 before June 15, 2007 and who were under 31 as of June 15, 2012. The Dream Act would raise the age of entry to 18, the date of entry to 2013 or 2014, and remove any age requirement at the time of application (see above). The RAC Act would move the date of entry to before 2012 (p. 6). These changes would allow far more people to apply.

In any case, the decision to ignore the plight of legal immigrant dreamers is baffling from a political standpoint. Including legal immigrant children in the Dream Act would 1) remove the criticism that the bill is unfair to legal immigrants, 2) create a new constituency to advocate for the bill, and 3) not increase the applicant pool any more than the Act’s existing changes to DACA eligibility. Someone should ask these members why they have chosen to limit their bills in this way.