What to do when confronted with the failures of U.S. maritime protectionism? Call for more protectionism, of course. That, at least, is the apparent attitude of some members of Congress.

A notable aspect of the Jones Act debate is that the law’s supporters often admit, albeit tacitly, that it isn’t working very well. Rep. John Garamendi (D‑CA) is a case in point. Participating in a recent panel discussion at the Brookings Institution, Rep. Garamendi readily conceded the enervated state of U.S. shipbuilding. “What remain of the American shipyards”—approximately 300 shipyards have closed since 1983—consist of “mostly small shipyards,” according to the California Congressman, as well as a few large ones which are “producing ships for the Jones Act but not for the international trade.”

Rep. Garamendi also freely acknowledged that, beyond the decline in shipyards, the United States also suffers from a lack of merchant mariners. Should the federal government call upon U.S. merchant mariners to crew the ships needed to deploy and sustain U.S. forces in time of war, Rep. Garamendi said that current projections show it falling 2,800 short (A 2017 government report found the deficit to be 1,839. This, however, was a best-case scenario assuming every mariner would be available and willing to sail).

This lack of mariners is no surprise given the steep decline in Jones Act-eligible ships, which have fallen from 326 in 1982 to just 99 today. In sum, fewer shipyards are building fewer ships which in turn employ fewer merchant mariners. Everything is trending in the wrong direction.

But if you were expecting Rep. Garamendi to reconsider his support for maritime protectionism in the wake of such failings, think again. Not only does he remain an ardent defender of the Jones Act, Rep. Garamendi believes that the maritime industry’s salvation is to be found in extending similar provisions to other areas of maritime commerce.

Citing the example of similar laws in Russia, India, and China—those noted paragons of wise economic policy—Rep. Garamendi used his Brookings appearance to highlight a bill called the Energizing American Shipbuilding Act. This legislation, which he vowed to re-introduce in a recent letter both he and Sen. Roger Wicker (R‑MS) sent to senior Trump administration officials, would mandate that 15 percent of liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and 10 percent of oil exports be carried aboard ships that are U.S.-flagged, U.S.-crewed, and U.S.-built.

This bill, if passed, would be a disaster.

Such requirements essentially amount to a giant tax upon U.S. energy exports that would make them less attractive to foreign buyers. But don’t take my word for it. According to a 2015 Government Accountability Office report on the subject, requiring U.S.-built-and-flagged carriers to transport U.S. LNG would “be associated with about 24-percent higher shipping rates if all of the additional cost were passed on to the buyer.”

That’s in large part due to the vastly higher cost associated with producing an LNG carrier in the United States compared to foreign shipyards. In fact, the GAO estimates that a U.S.-built carrier could cost up to $675 million (the precise cost is unknown as no such vessel has been built in the United States since 1980) while one can be built in South Korea for $175 million. Furthermore, even a U.S.-built LNG carrier may still need to rely extensively upon South Korean expertise. As the GAO pointed out in its analysis, one of the U.S. shipyards it spoke with admitted that building an LNG carrier might require hiring “250 to 300 skilled Korean workers for the duration of the build time to ensure the work is done correctly.”

David Ricardo is no doubt spinning in his grave.

But it gets worse. While Rep. Garamendi’s bill lacks the Jones Act’s U.S. ownership requirement, in one key way it is actually more draconian than the 1920 law. Under the Jones Act, the domestic-build requirement is considered to be satisfied if “major components of the hull and superstructure” are fabricated in the United States. The Energizing American Shipbuilding Act, however, extends this requirement to items such as engines and propellers that are almost invariably imported when constructing a Jones Act-eligible commercial ship.

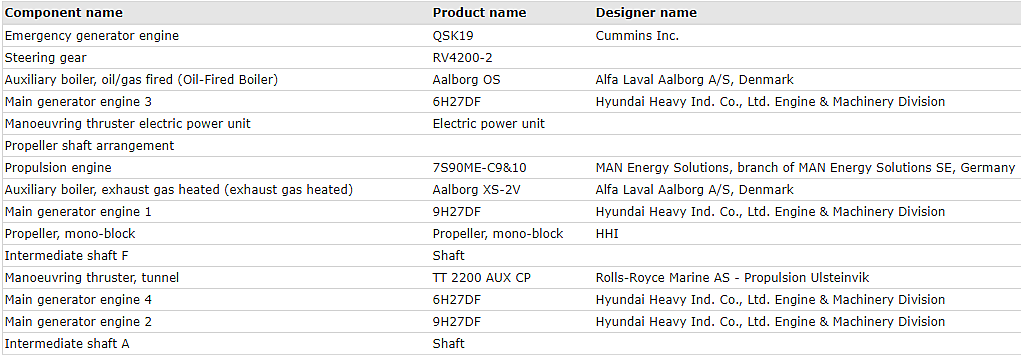

A list of the key machinery used in Daniel K. Inouye, a Jones Act containership launched last year, for example, reveals a huge reliance upon foreign components:

Replace foreign components with domestic ones and the cost of building an LNG carrier will no doubt further balloon. Indeed, if such restrictions are imposed the GAO’s upper estimate of $675 million to build a U.S. LNG carrier may well prove overly optimistic.

The Jones Act is premised upon the unwritten bargain that in exchange for the costs of protectionism it will ensure a strong U.S. merchant marine. But while the law has produced very real costs, it has manifestly failed to generate its promised benefits, with the United States experiencing a long downward trend in shipyards, ships, and the mariners that crew them. Rather than admit to any shortcomings in current policy, however, Jones Act defenders seize upon these very failings to justify or even strengthen them. This is “heads I win, tails you lose” logic at its worst.

The U.S. maritime industry isn’t being protected, it’s being poisoned. It isn’t being spared from foreign competition but deprived of it. And the results are entirely predictable. Protectionism has been tried, and protectionism has failed. It’s time for a change in course.