Conor Clarke’s second comment at The Atlantic blog on the study, “What to Do About Climate Change,” was that:

Goklany’s estimates are based on global aggregates that hide the unequal distribution of the climate change burden. Yes yes, I know Manzi will say that’s not decisive: As long as global GDP is higher, we can redistribute our way out of the problem more effectively tomorrow than we can today. I would be more comfortable with that debate if I thought vast international restributions of income in the name of global equity were more likely tomorrow than they are today.

RESPONSE:

Global greenhouse gas controls will also have uneven consequences. First, cost of controls will vary from country to country, and sector to sector. Second, because the impacts of climate change will also vary from area to area, the benefits of control will necessarily be uneven. They will also vary over time. In fact, for some sectors, some areas may benefit even under the IPCC’s warmest scenario, at least through the foreseeable future. For example, through at least 2085, climate change would increase the global population at risk of water stress (see Figure 2, here). Therefore controlling climate change would exacerbate the global population at risk of water stress. So both the costs and benefits of climate change controls will also be distributed unevenly. Third, as noted here, implementing climate change controls that go beyond no-regret actions requires that today’s poorer generations delay solving the real problems they face here and now and instead put resources into solving the hypothetical problems that may (or may not) confront tomorrow’s far wealthier — and technologically better-endowed — populations. Nothing equitable about that.

Conor Clarke’s third comment was:

… I’m suspicious of the ethical calculus that says we should not focus on one large global problem because larger global problems might exist. [Emphasis in the original.] That kind of moral math rarely corresponds to the political reality. (Do you think the average congressperson opposed to Waxman-Markey has trouble sleeping at night over new cases of malaria or global hunger?) Nor does it correspond to the historical responsibility: Industrialized nations are more responsible for the global problems created by climate change than the problems of population growth.

RESPONSE:

I am puzzled as to why Conor suggests we should focus on one large global problem — presumably climate change — when larger global problems might exist. Why should we focus on any problem when other larger ones are unresolved?

Nevertheless, Conor is correct, political decisions are rarely based on ethical calculus — the more’s the pity.

In any case, my paper doesn’t advocate twiddling our thumbs when it comes to climate change. Yes, it doesn’t advocate aggressive action (going beyond no-regret actions) to control climate change in the near to medium term. Instead it focuses on increasing adaptive capacity, technological prowess, and sustainable economic development which would enable society to respond to whatever problems it may face in the future, including climate change. As the paper shows, aggressive mitigation would not be the best approach to advance human well-being and deal with today’s urgent problems while advancing the ability to address tomorrow’s problems (see Table 5, here).

Specifically, it would reduce vulnerability to today’s urgent climate-sensitive problems — e.g., malaria, hunger, water stress, flooding, and other extreme events — that might be exacerbated by climate change. Second, it would strengthen or develop the institutions needed to advance and/or reduce barriers to economic growth, human capital, and the propensity for technological change. Together, these two elements would improve both adaptive and mitigative capacities, as well as the prospects for sustainable economic development. Third, my paper advocates implementing no-regret mitigation measures now, while expanding future no-regret options through research and development of mitigation technologies. Fourth, it would let the market pick winners and losers among the various no-regret options. Fifth, it would continue research into the science, impacts and policies related to climate change, and monitoring of impacts to provide early warning of any “dangerous” impacts were they to be manifested.

Although Conor is probably correct in suggesting that politicians rarely undertake any ethical calculus in arriving at their decisions, many have nevertheless asserted that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a moral imperative. See, e.g., here. But what is the basis for this claim?

These claims are never accompanied by any analysis that compares the magnitude and urgency of climate change versus other problems that humanity faces today or in the foreseeable future. The only such comparative analyses that have been undertaken are those done as part of Lomborg’s Copenhagen Consensus exercise and my Cato paper [and their prior versions, see, e.g., “Potential Consequences of Increasing Atmospheric CO2 Concentration Compared to Other Environmental Problems.” Technology 7S (2000): 189–213 and Copenhagen Consensus 2004.]. And these provide no support for the oft-repeated but unsubstantiated claim that climate change is a moral imperative given the many other real problems that exist today.

Finally, Conor raises the issue of historical responsibility of industrialized nations for global warming. As Henry Shue, an Oxford ethicist, notes, “Calls for historical responsibility in the context of climate change are mainly calls for the acceptance of accountability for the full consequences of industrialization that relied on fossil fuels.” [Emphasis added.] But a fundamental premise behind these calls is that the “full consequences of industrialization” are negative. This is one more unsubstantiated claim.

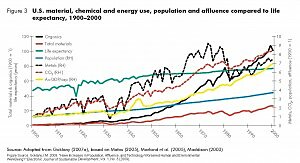

In fact, by virtually any objective measure of human well-being — e.g., life expectancy; infant, child and maternal mortality; prevalence of hunger and malnutrition; child labor; job opportunities for women; educational attainment; income — humanity is far better off today that it was before the start of industrialization, due to the cycle of progress and economic surpluses fueled for the most part by fossil fuels. In addition, hunger and child labor are as low — and job opportunities for women as high — as they are today partly due to the direct effect of fossil fuel powered labor saving technology. This is clearly true for industrialized countries. Figure 1 shows that life expectancy — perhaps the single most important indicator of human well-being — increased for the U.S through the 20th century, even as CO2 emissions, population, affluence, and material, metals, and organic chemical use increased. Matters have also improved in developing countries. And global life expectancy increased from 31 years in 1900 to 47 years in the early 1950s to 69 years today.

Notably, much of the improvement of human well-being in developing countries is due to the transfer of technology (including knowledge) from industrialized countries to developing countries. Moreover, a substantial share of the income of many developing countries comes directly or indirectly from trade, tourism, aid, and remittances from industrialized countries. Consequently, developing countries are far ahead of today’s industrialized countries at equivalent levels of economic development.

For instance, as noted here (pp. 20–21):

in 2006, when GDP per capita for low income countries in PPP-adjusted terms was $1,327, their life expectancy was 60.4 years, a level that the U.S. first reached in 1921, when its GDP per capita was $5,300. Surprisingly even Sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s developmental laggard, is today ahead of where the U.S. used to be. In 2006, its per capita GDP was at the same level as the U.S. in 1820 but the U.S. did not reach Sub-Saharan Africa’s current infant mortality level until 1917 when, and life expectancy until 1902, by which time the U.S. was far wealthier. [All GDP figures are in terms of real 1990 dollars, adjusted for purchasing power.]

Thus, empirical data do not support the underlying premise that industrialization of today’s developed countries has caused net harm to developing countries.

So what is it that industrialized countries have a “historical responsibility” for? For the diffusion of knowledge and technology that they developed and which helped developing countries improve their well-being, and for helping increase incomes in the latter through trade, aid, remittances, and tourism?

As noted at Reason on-line: “Who knows, in accounting for both benefits and damages [associated with greenhouse gas emissions], Bangladesh would not end up owing the United States!”