The danger posed by illegal immigrant drunk drivers is a major point of contention in the debate over immigration policy. Significant media attention and the occasional tragedy contribute to the notion that illegal immigrants commit drunk driving (DUI) offenses at an alarming rate. In a recent interview, former Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) director Tom Homan went so far as to label DUI offenses committed by illegal immigrants as a “public safety threat.” Indeed, law enforcement officials and immigration authorities alike continue to state that illegal immigrants are significant DUI offenders, despite research that finds no effect of illegal immigration on DUI related deaths or criminal activity in general.

In 2017, nearly 11,000 people were killed in alcohol-impaired-driving accidents, meaning that drunk driving is responsible for almost 29 percent of all traffic deaths. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimates that alcohol-related deaths in 2017 were highest in Texas, California, and Florida – three states with large illegal immigrant populations as well as large populations in general. If illegal immigrants are more likely to be drunk drivers, places with larger illegal immigrant shares of the population will have more alcohol-related traffic deaths. Below, we examine whether this is the case.

Methodology

We collected raw data on traffic deaths from the NHTSA Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) database for the 2010–2017 period. The FARS data provide comprehensive records on deaths in motor vehicle crashes, including details on drivers, victims, and details of the crash. To determine whether deaths were the result of alcohol impairment, we use data on drivers’ blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) and whether the police reported alcohol involvement through FARS. All 50 states and the District of Columbia passed laws setting the legal BAC limit at 0.08g/DL, so we adopt this same threshold for our filters. Since the NHTSA uses methods to impute missing BAC values, we were not able to replicate their annual estimates exactly. However, our figures using the two previous filters yield very similar results. For instance, NHTSA estimates a total of 10,874 alcohol-related deaths in 2017 and our filtering method yields 10,850 – a difference of just 0.22 percent. We aggregated these data up to the state-year level.

Our measure of the illegal immigration population and state-level demographic data come from the Pew Research Center and American Community Survey (ACS) 1‑year estimates available through IPUMS, respectively. As a robustness check, we calculate state-level estimates for the share of Hispanic noncitizens as a proxy for the likely illegal immigrant population. At a minimum, their numbers are closely correlated with the number of illegal immigrants. That means that the results for regressions where the independent variable is the illegal immigration population as estimated by Pew should be similar to those where the Hispanic noncitizen population is the independent variable.

To test whether larger illegal immigrant population shares correlate with increased deaths in drunk driving accidents, we ran two-way fixed effects regressions that regress the log traffic death rate per 100,000 on the population share of illegal immigrants and Hispanic noncitizens by state. State fixed effects account for level differences across states, such as state drinking culture, while year effects control for national trends affecting all states such as secular changes in road injuries. Standard errors in each regression are clustered by state to account for arbitrary autocorrelation in the error term.

Results

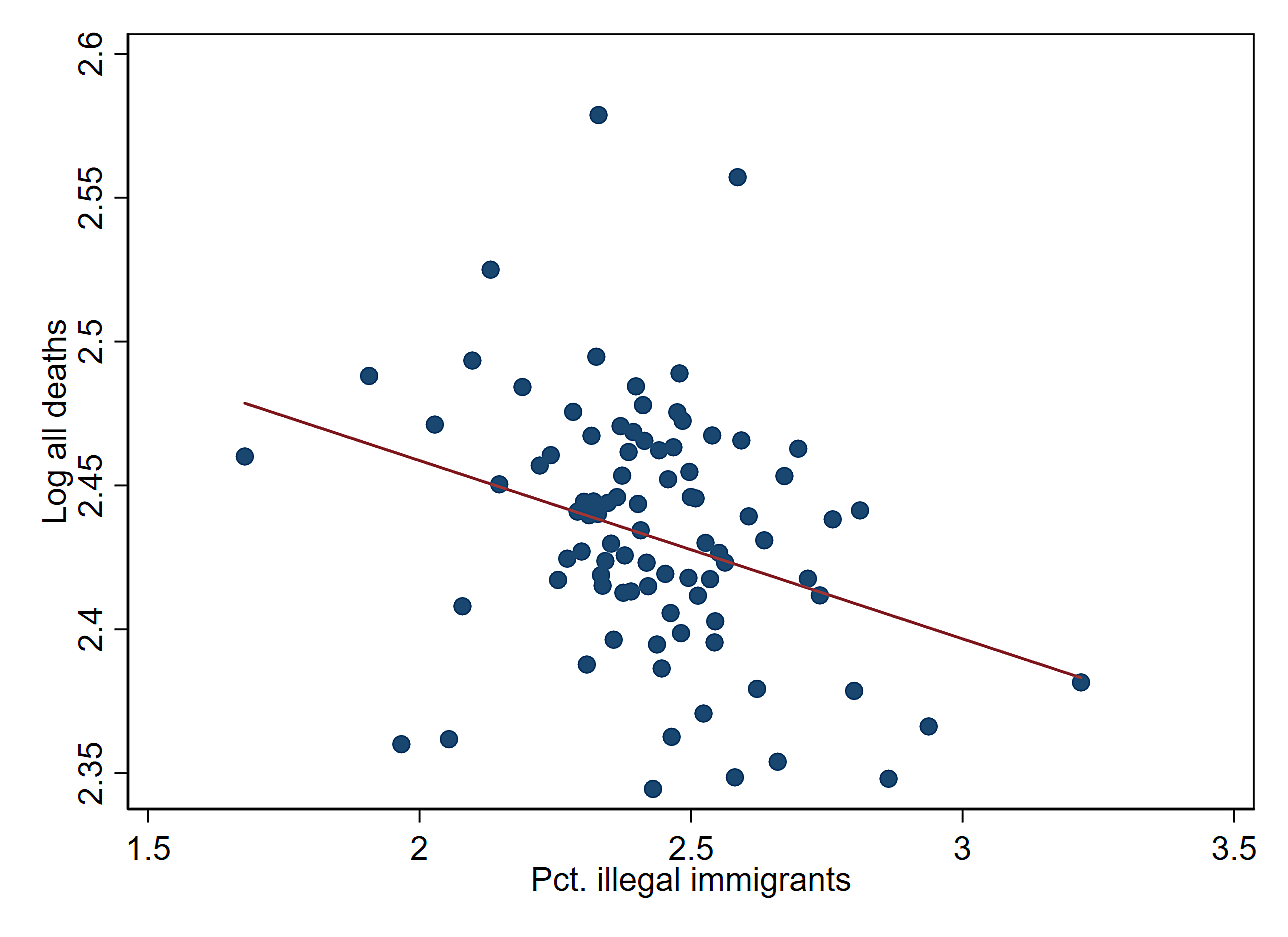

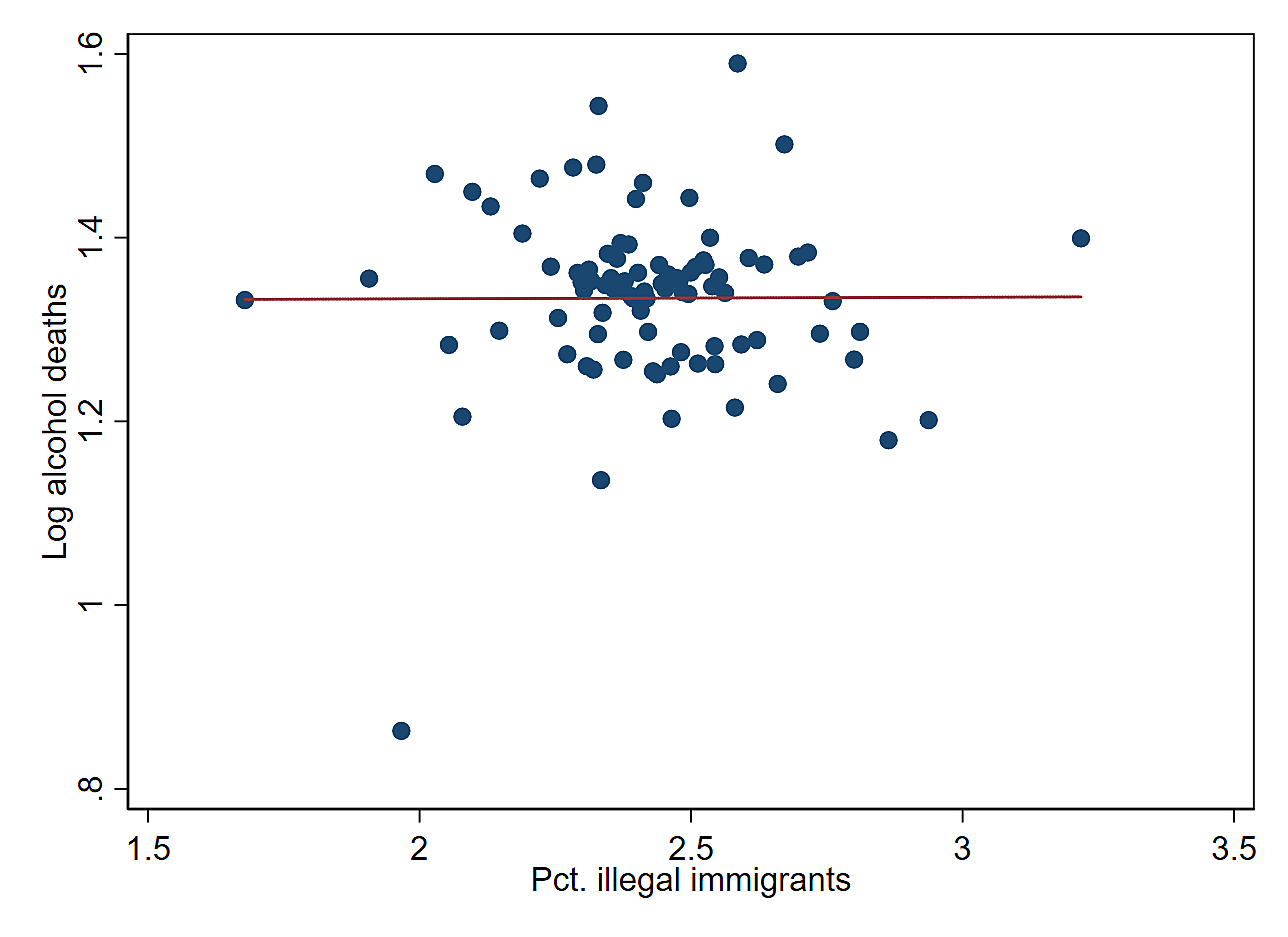

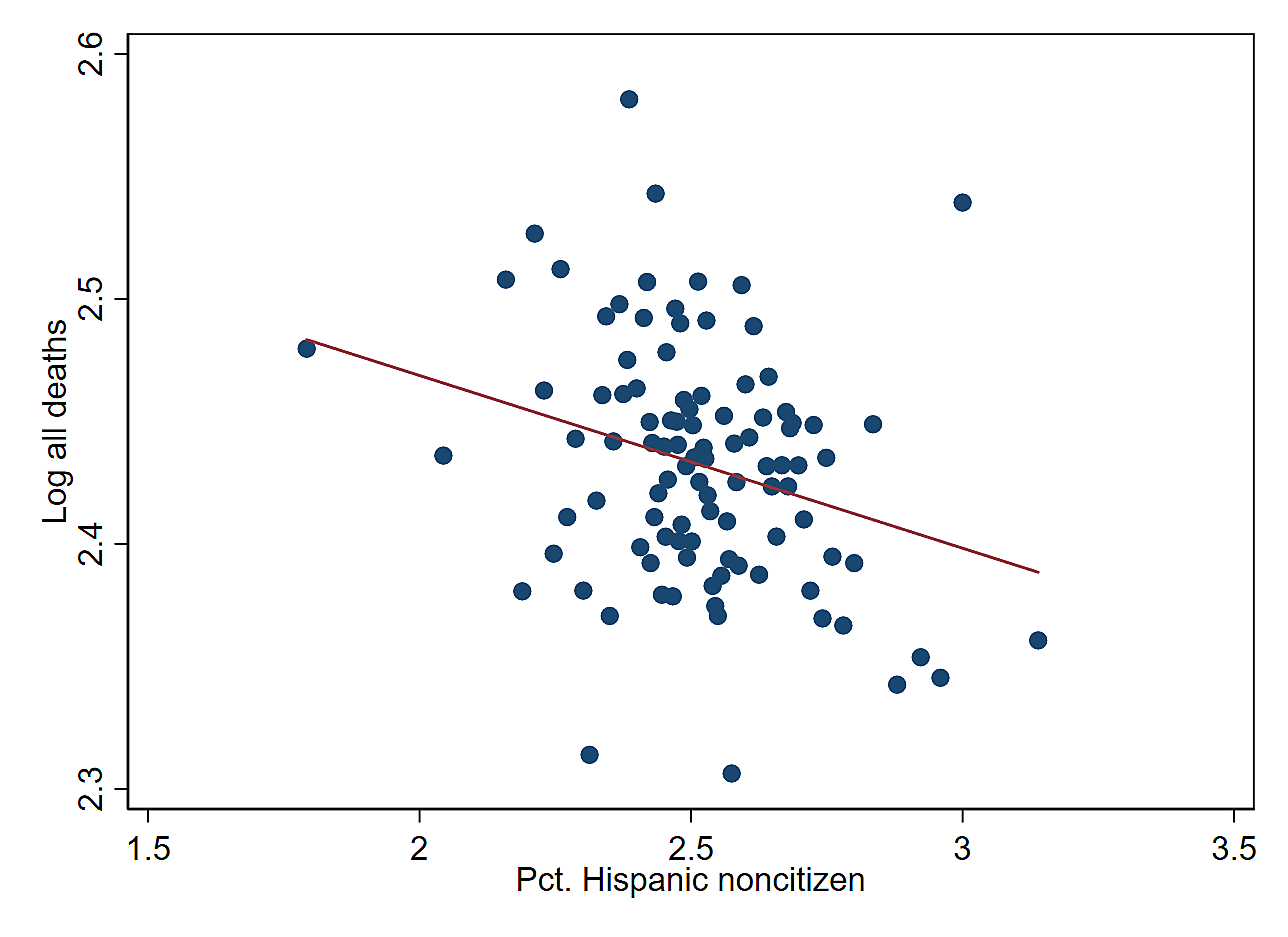

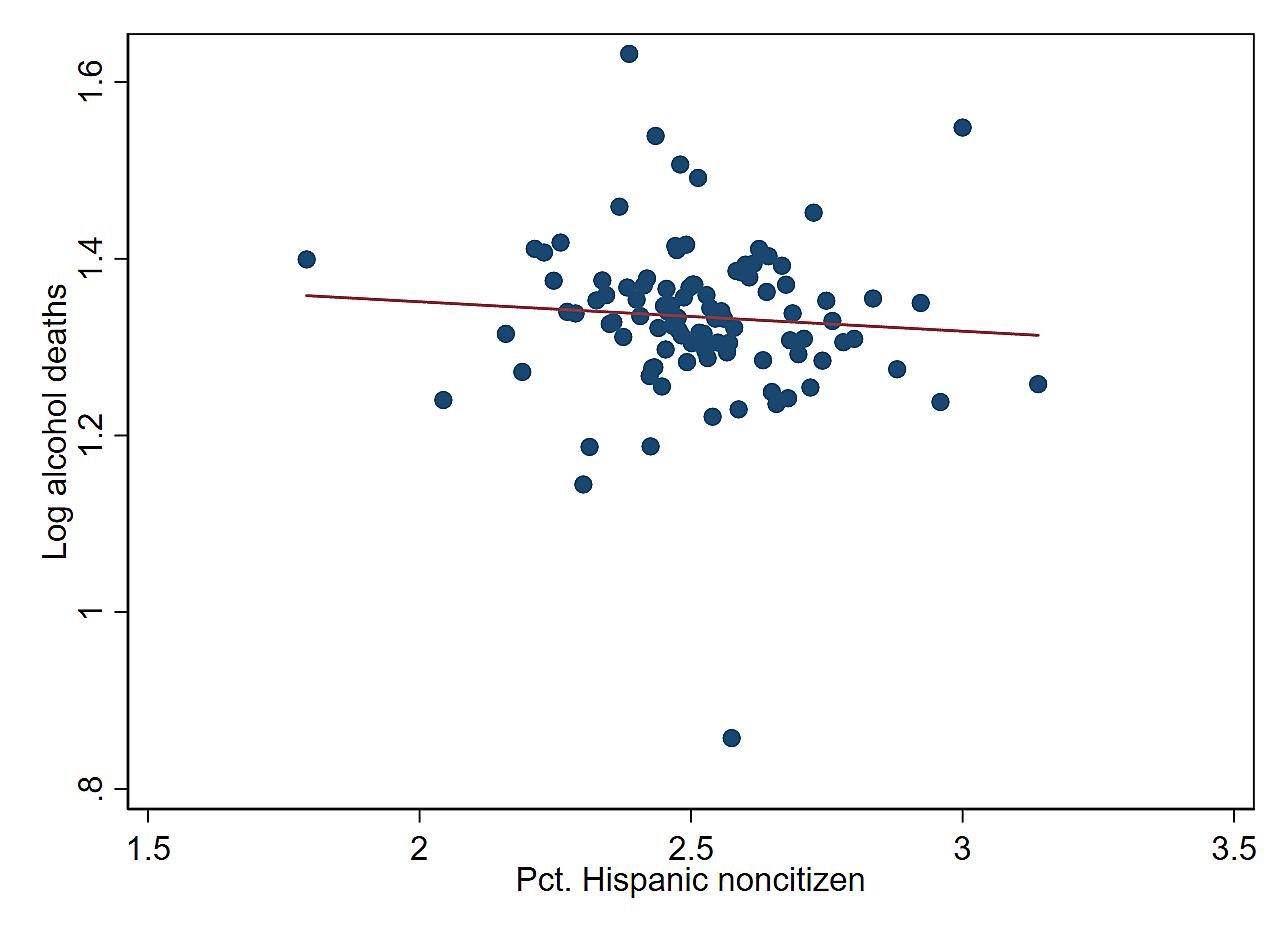

Our results show that illegal immigrant populations are not correlated with alcohol-related traffic deaths (Table 1). For both the overall level of traffic deaths and alcohol-related deaths, we find a negative partial correlation with the state population share of illegal immigrants. Interestingly, we find that places with larger illegal immigrant shares are significantly associated with fewer per capita traffic deaths. However, this result falls out of significance after accounting for state trends. We find no significant evidence for a relationship between illegal immigrant population share and the alcohol-related drunk driving death rate. Considering Hispanic noncitizens as a proxy for likely illegal immigrants yields similar results (Table 2). We continue to find no statistically significant association with an increased risk of death through alcohol-related crashes.

Table 1

Traffic Deaths and Illegal Immigrant Population Shares

Table 2

Traffic Deaths and Hispanic Noncitizen Population Shares

These regression above are also summarized by binned scatterplots in Figures 1–4. Figure 1 shows a statistically significant negative relationship between the illegal immigrant share of the population and the death rate from all traffic accidents by state from 2010–2017. Figure 2 shows no statistically significant relationship between alcohol-related traffic deaths and the illegal immigrant population share by state from 2010–2017. Figure 3 shows a statistically significant negative relationship between the noncitizen Hispanic share of the population and the death rate from all traffic accidents by state from 2010–2017. Figure 4 shows no relationship between the noncitizen Hispanic share of the population and the alcohol-related death rate from all traffic accidents by state from 2010–2017.

Figure 1

All Traffic Death Rate and Illegal Immigrant Population Share by State, 2010–2017

Sources: Authors’ calculations using the 2010–2017 FARS, Pew (2019), and 2010–2017 ACS 1‑year estimates from IPUMS.

Figure 2

Alcohol-Related Traffic Death Rate and Illegal Immigrant Population Share by State, 2010–2017

Sources: Authors’ calculations using the 2010–2017 FARS, Pew (2019), and 2010–2017 ACS 1‑year estimates from IPUMS.

Figure 3

All Traffic Death Rate and Noncitizen Hispanic Population Share by State, 2010–2017

Sources: Authors’ calculations using the 2010–2017 FARS and 2010–2017 ACS 1‑year estimates from IPUMS.

Figure 4

Alcohol-Related Traffic Death Rate and Noncitizen Hispanic Population Share by State, 2010–2017

Sources: Authors’ calculations using the 2010–2017 FARS and 2010–2017 ACS 1‑year estimates from IPUMS.

Conclusion

We find no statistical evidence to suggest that places with more illegal immigrants are more at risk for drunk driving deaths. Of course, there are individual instances to the contrary and those illegal immigrants who commit real crimes should be punished like everybody else, but their presence doesn’t seem to affect overall drunk driving deaths. Although our regressions results are correlative and not causal in nature, they suggest that illegal immigrants do not affect overall drunk driving deaths.