Traditional welfare programs have always suffered from an internal contradiction: Welfare benefits helped meet the poor’s immediate material needs, but simultaneously set up incentives that can penalize work, marriage, and other routes to self-sufficiency. The combination of lost benefits, taxes, and employment costs can often mean that someone leaving welfare for work would see little, if any, increase in short-term income.

This is unfortunate because many families trapped in the welfare system do not require long-term assistance. Rather, many people apply for welfare because of a short-term financial problem: for instance, women who become divorced, those faced with eviction, or a sudden health issue. In such cases, signing the person up for traditional welfare may do more harm than good, failing to solve the immediate crisis, while locking the person into long-term dependency. A better approach would be to help people meet those immediate needs while also diverting them from the welfare system.

The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunities Act (PRWOA) authorized states to experiment with alternative ways to assist applicants that did not involve signing them up for traditional welfare. Non-recurrent short-term benefits can take the form of a variety of direct or non-direct assistance, provided it is (1) designed to deal with a specific crisis or episode of need; (2) is not intended to meet recurrent or ongoing needs; and (3) will not extend beyond four months. A similar approach has been separately authorized for Supplemental Security Income.

States have used this authority to provide assistance ranging from educational services (Oregon) to childcare assistance (Colorado) to clothing allowances (Massachusetts, New York, and Texas). Most often, states have used this authority to pursue one of three types of diversion programs.

The most common diversion effort provides a lump sum cash payment in lieu of traditional welfare payments. The second most common approach is some form of mandatory assisted job search, in which applicants are required to undertake a structured search for employment for a designated time before becoming eligible for benefits. Additionally, a few states have pursued a strategy of requiring applicants to first seek help from alternative resources, such as their families, private charities, or other government programs. Some states use multiple forms of diversion, and a handful utilize all three approaches.

Lump Sum Payments

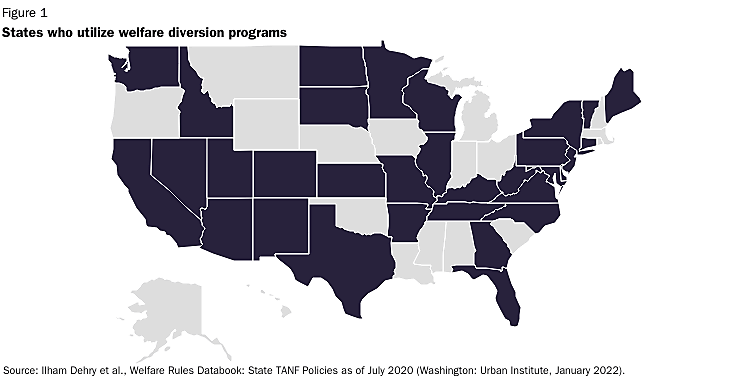

A few states began to experiment with diversion as early as the 1980s. Georgia, Utah, and Virginia, among others, utilized authority under Section 1115 waivers to offer a one-time payment to individuals who were judged to be job-ready or who had other sources of income that made full participation in cash welfare (then Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC) unnecessary. Experimentation accelerated with the PRWOA, which converted AFDC to a block grant (TANF), and gave states much greater freedom to manage the funds that they received without the need for a waiver process. Today, 32 states and DC have some sort of lump sum diversion program on the books (see Figure 1).

However, the details of these programs vary widely from state to state. For instance, Wisconsin provides assistance in the form of a cash loan, while many other states provide a straight cash benefit, and others pay vendors (such as landlords) directly.

The maximum size of the lump sum payment is frequently some multiple of the value of monthly TANF benefits, ranging from three months in Idaho (about $900) to a year’s worth in Tennessee (roughly $4,600). Other states like Colorado allow diversion participants a maximum benefit of $2,500 regardless of family size, determined on a case-to-case basis. Conversely, New Jersey gives three-person family applicants a maximum benefit of $750 once in a lifetime. Nevada handles diversion on a case-by-case basis according to the particular needs of the family with no set maximum. For the most part, the maximum lump sum approximates three to four months’ worth of benefits. Similarly, the amount of time a diversion recipient would be ineligible for TANF ranges from no ineligibility period in six states to 12 months of ineligibility in six other states.

Most often there are few, if any, restrictions on how the lump sum payment can be used. In practice, they have been used to pay off back debt as well as for childcare expenses, car repairs, medical bills, rent, clothing, and utility bills. In many cases, the payments have been used for business- or job-related expenses such as tools, uniforms, or business or professional licenses. A small number of states restrict the use of payments to job-related expenses, although those are usually defined very broadly to include things such as childcare, transportation, or even moving expenses for a new job.

Mandatory Job Search

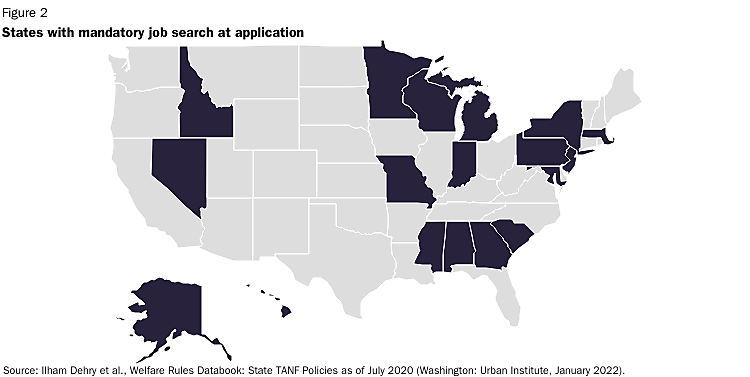

Sixteen states have the option of requiring applicants to undertake a structured job search before receiving TANF benefits (see Figure 2). In most cases, the state assists with the job search in some way, such as providing job contacts, leads, and access to a resource center where applicants can prepare resumes and conduct job searches. Some provide classes in resume writing, interview skills, and job search techniques. States have even been known to provide childcare and transportation assistance.

The length of the required job search varies from as little as two weeks in South Carolina to as long as six weeks in Alabama and Georgia. Often, this is not a delay in receiving benefits but simply a requirement to do a job search during the period normally required to process a welfare application. Some states take the job search more seriously than others. Indiana, Missouri, and Nevada, for example, require application to at least 10 jobs per week; Alabama, on the other hand, requires only two applications over its entire six-week processing period. Moreover, few states require any sort of documentation or proof of job search activities.

Unlike lump sum payment programs, mandatory job searches do not disqualify an applicant from future TANF receipt. But finding a job would make it much less likely that the applicant would need government assistance.

Alternative Resources

Finally, seven states have programs designed to encourage welfare applicants to attempt to access alternative resources before enrolling in TANF. These programs generally operate informally without specific guidelines, but usually involve caseworkers helping would-be welfare applicants in seeking help from family, charities, or even non-TANF government programs. Participants are not disqualified from TANF, but the goal of the program is to make TANF unnecessary. It should be noted that even in states that have this type of diversion program on the books, it is rarely used, most likely because it requires extensive involvement from caseworkers.

Stay Tuned

There is solid evidence diversion programs are a win-win opportunity, reducing welfare participation and expenditures while helping recipients. Yet, even in those states with diversion programs on the books, those options are rarely utilized. This is a lost opportunity.

Next week, we will look at the research on the success of these programs, and reasons why states have still been reluctant to pursue them. But diversion represents a clear opportunity for bipartisan efforts to reform welfare.