Every presidential candidate promises to “reduce income inequality” by raising tax rates on the rich and increasing transfer payments (including tax credits and in-kind benefits) for the middle class. Yet the widely-used flawed data from Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez exclude both taxes and transfers. Income measures that exclude taxes and transfers cannot tell us whether taxes or transfers are high or low, and cannot be directly affected by higher taxes on some or higher transfers to others (because such policies are ignored in the data).

A simple table adapted from the 2017 Consumer Expenditure Survey, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, may be sufficient to show how crucial it is to take account of taxes (including refundable tax credits), and also to adjust average income for the different number of people and workers per household.

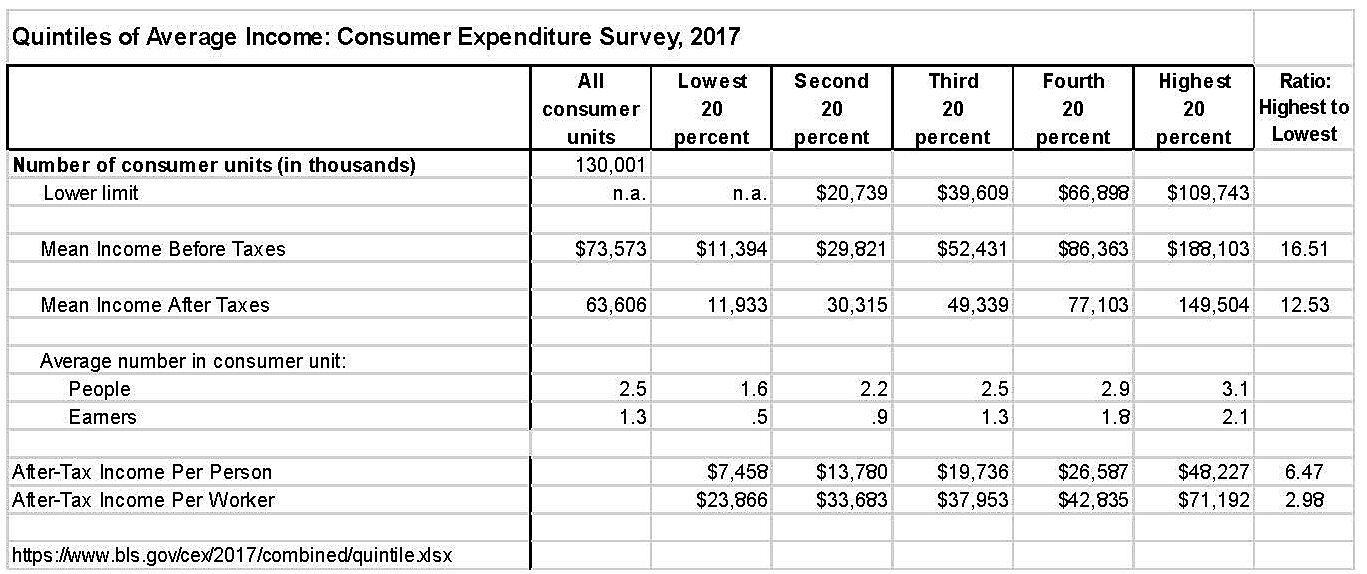

Incomes are shown by fifths (“quintiles”), with the lowest 20% on the left and highest on the right.

The second row shows the “lower limit” of pretax income needed to counted be in each quintile. The next two rows show mean (average) income before and after taxes.

The column at the far right shows a ratio of highest to lowest income, called the 80/20 ratio, which a common gauge of inequality. It shows that the highest 20% earned 16.5 times as much as the lowest 20% before taxes, but only 12.5 times as much after taxes.

But simply adjusting household income for taxes is not enough. Average incomes cannot be properly compared between the highest and lowest quintiles because there are three times as many people per consumer unit (household) in the highest 20% as there are in the lowest. And there are four times as many workers in the highest 20% as there are in the lowest.

By adjusting for different household size, we find the highest 20% earned only 6.5 times as much after-tax income per person as the lowest 20%.

But income is likely to be higher in households with two or more workers than it is in households with no workers or only one. So, that last row measures average after-tax income per worker in the highest and lowest quintiles (and those in between).

By further adjusting for the different number of earners, the highest 20% earned only 3 times per worker as much as the lowest 20%, after taxes.

Properly understood, the facts about U.S. after-tax income distribution and growth are insufficiently alarming to justify the political misuse of questionable pretax, pretransfer income statistics as a false argument for redistributing after-tax income.