Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip, among others, has repeatedly warned that “this year’s tax cut may overheat an economy already near full employment.”

This equivocal prediction relies on a theory that inflation is caused by combining low unemployment and large structural (cyclically-adjusted) budget deficits. Inflation is assumed to be a national rather than global phenomenon, and its cause is assumed to be fiscal rather than monetary.

To support this fiscal theory that tax cuts are inflationary, the evidence Greg Ip and others have always turned to is this brief sample from U.S. history, 1965 to 1967:

“In 1966, inflation, which had run below 2% for nearly a decade, suddenly accelerated to over 3%. Some of the circumstances echo the present: unemployment had slid to 4%, taxes had been cut and federal spending for the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ programs was surging.”

This legendary “guns and butter” explanation suggests inflation “suddenly accelerated” in 1966 largely because “taxes had been cut” thus supposedly pushing budget deficits much higher than prudent at a time of 4% unemployment. The Fed’s reluctance to even keep the fed funds rate barely above the known year-to-year inflation trend is barely mentioned. Treasury dollar exchange rate policy, including slipping ties of coins to silver and of the dollar to gold, is ignored.

In February 1964, the Kennedy/LBJ tax cut reduced all marginal tax rates by about 30% over two years, with the top rate falling from 91% to 70% by1965 and the lowest rate from 20% to 14%. Corporate tax rates were also reduced, particularly for small firms.

Contrary to Mr. Ip, the 1964–65 “tax cuts” can’t possibly explain why inflation “suddenly accelerated” in 1966, because tax revenues in 1966–67 were rising rather than falling, and budget deficits were tiny.

As a percentage of GDP, federal revenues rose from 16.4% in 1965 to 16.7% in 1966 and 17.8% of GDP in 1967 (higher than any year from 1956 to 1963). But percentages of GDP understate the real gain, because real GDP was rising so fast.

Measured in constant 2009 dollars to adjust for inflation (from Table1.3 of the Budget’s Historical Tables), real federal revenues had long been virtually stagnant before the Kennedy tax cuts, rising only 7.5% between 1952 and 1963 –from $657.7 billion in 1952 to $707.1 billion in 1963.

After tax rates came down, by contrast, real revenues rose by 29% in just four years. Real revenues rose to $735.6 billion in 1964, $752.5 billion in 1965, $819.8 billion in 1966, $911.9 billion in 1967. After a brutal 10% surtax was added in June 1968, real revenues initially fell to $904.6 billion (17% of GDP), though revenues briefly surged in the first half of 1969.

The budget deficit in 1966 was a trivial 0.5% of GDP –down from 0.8% in 1963 (before the tax cuts), and still just 1% of GDP in 1967. To properly judge the alleged “fiscal stimulus” theory, however, we need to adjust deficits for the state of the economy by removing “automatic stabilizers” that enlarge deficits in recessions: Revenues naturally fall with falling payrolls and profits, while unemployment and other means-tested benefits rise.

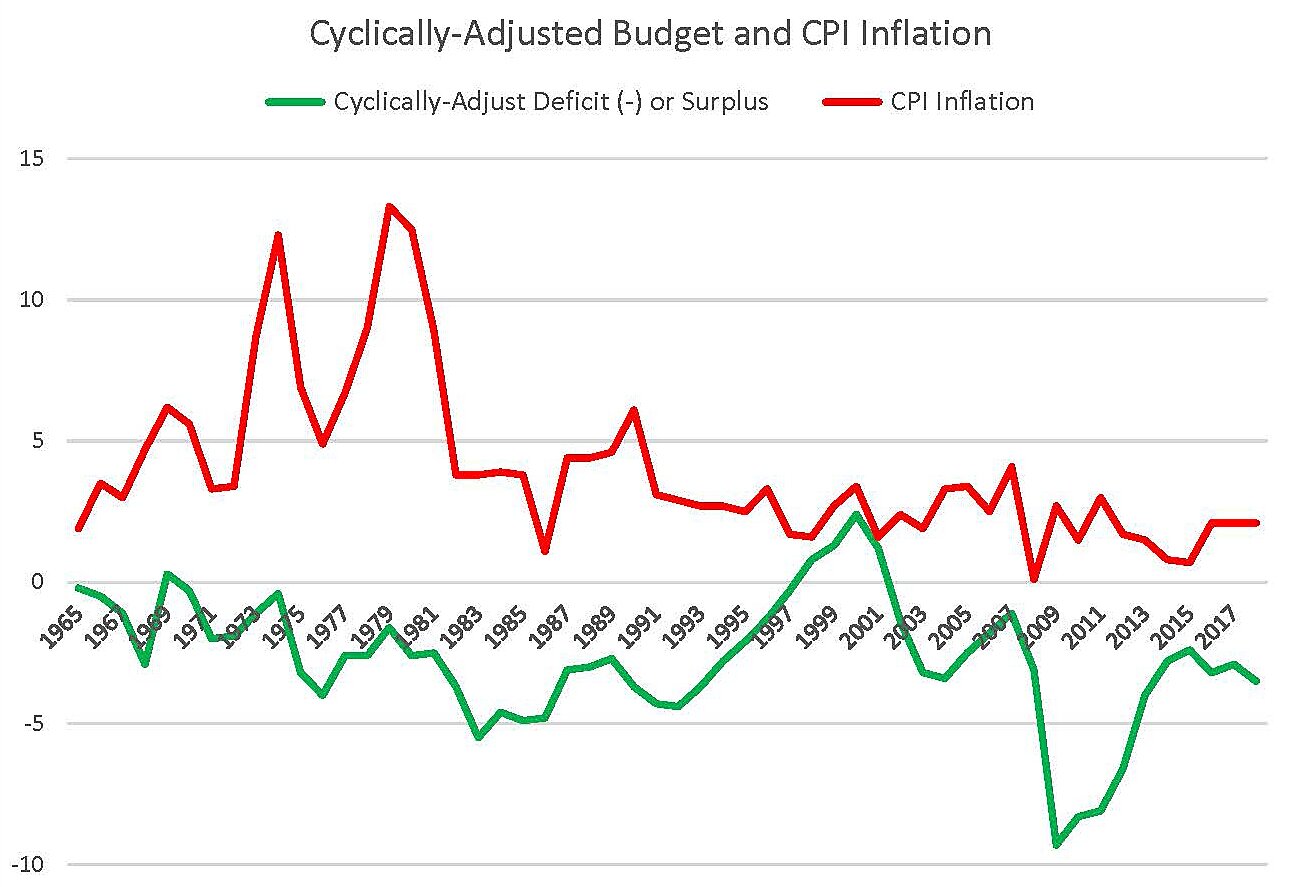

The Graph compares Congressional Budget Office cyclically-adjusted budget deficits with changes in consumer price inflation. Just as there is no evidence that large cyclically-adjusted budget deficits stimulate “overheating” of nominal GDP (as endless Japanese experiments attest), there is likewise no evidence that larger cyclically-adjusted deficits cause (or are even loosely associated with) higher inflation.

In fact, cyclically-adjusted deficits were largest when inflation was low and/or falling in 1983–86 and 2009–14. And such deficits were small during the big inflations of 1973–75 and 1979–81. Cyclically adjusted deficit were near zero in 1966–67 when an uptick in (global) inflation was supposedly caused by tax cuts and “guns and butter” spending. Contrary to the theory, cyclically-adjusted budget surpluses in 1998–2000 were not associated slow growth of real GDP or falling inflation.

Cutting tax rates by 30% in 1964–65 did indeed result in faster growth of real GDP, but that also produced rapid growth of real tax receipts. No measure of budget deficits grew larger because of those misnamed tax cuts, and deficits were insignificant until 1968. There was no “fiscal stimulus” (as Keynesians define it) from the Kennedy tax cuts. The deficit reached a modest 2.8% of GDP only after the 1968 surtax, but nothing in1968 explains why CPI inflation “suddenly” touched 3% in 1966.

In short, efforts to blame creeping global inflation in the late 1960s on U.S. budget deficits, much less on lower tax rates that actually brought in a huge revenue windfall, is inconsistent with any relevant facts.