The Department of Labor (DoL) issued an interim final rule (IFR) on October 8 that substantially increases the wages for H‑1B workers. My colleague David Bier has analyzed the effect of the regulation here and here. This blog post will examine the main justifications given by the DoL for the increase in the minimum wages for H‑1B workers. The DoL gives two primary justifications to increase H‑1B minimum wages:

- H‑1B migrants reduce the wages of native-born Americans.

- H‑1B migrants displace native-born American workers.

The DoL cites many sources to support its justifications, but they rely on one peer-reviewed academic paper for hard numerical estimates of the impact of immigrants on the wages on native-born Americans: George Borjas’ 2003 paper “The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market,” published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE). The DoL IFR also cites Borjas’ 2014 book Immigration Economics that Cato held a book event for in 2014, but no empirical findings from it. The DoL specifically wrote:

In particular, some research suggests that a substantial increase in the labor supply due to the presence of foreign workers reduces the wages of the average U.S. worker by 3.2 percent, a rate that grew to 4.9 percent for college graduates.

Borjas’ QJE paper was published in 2003 and covered how immigrants affected the wages of Americans during the period of 1960–2000. Because the DoL cites Borjas’ work, we decided to replicate and expand upon Borjas’ regressions and focus on the 1990–2018 period to see how immigration affects the wages of workers with at least a college degree. We began our analysis in 1990 because that is when Congress created the H‑1B visa. Since the wages paid to workers on the H‑1B visa is the target of DoL’s IFR, this blog post focuses on the period when the H‑1B visa was in existence.

Methodology and Data

Immigrants and native-born American workers have different levels of education and experience in the labor market. Borjas’ great innovation was to group immigrants and native workers into cells based on their years of education and the number of years of experience, with the assumption that natives and immigrants with the same education and experience should be perfect substitutes in the national labor market. By grouping natives and immigrants thusly into cells based on their education and experience, he was then able to run regressions to see how the increase in immigrants in a specific education-experience cell affected the wages of natives in the same education-experience cell. Defining the education-experience cell in this way has the added benefit of providing variation in the supply of immigrant workers that can help identify how immigrants affect the wages of native-born American workers.

In Chapter 5 of his 2014 book Immigration Economics and section 7 of his 2003 QJE paper, Borjas takes a structural approach to estimating the labor market impact of immigration. The structural approach examines how the immigrant influx affects the relative wages of not only competing native workers, but also the cross effects on wage of other native workers from other education and experience cells. This blog post is an extension to his method in Chapter 4 of Immigration Economics where he only looks at how immigrants impact similarly educated and experienced native workers.

In particular, to make the model computationally less burdensome, Borjas employs a nested CES model where a specific assumption of the functional form for the aggregate production function allows for the estimation of a complete set of factor price elasticities that allow one to estimate how immigration affects the entire wage structure. Borjas first estimates these price elasticities and uses them to simulate the wage impact of immigrants on the preexisting workforce using actual shifts in the number of immigrants (see Table 5.2 in Immigration Economics).

Here, we replicated Borjas’ Table 5.2 and added the years 2014–2018 (pooled together and labeled 2018) to account for the most recent influx of immigrants. We also added a table to investigate the number of hours worked by native-born Americans, to investigate whether they push American workers out of the labor force.

Results

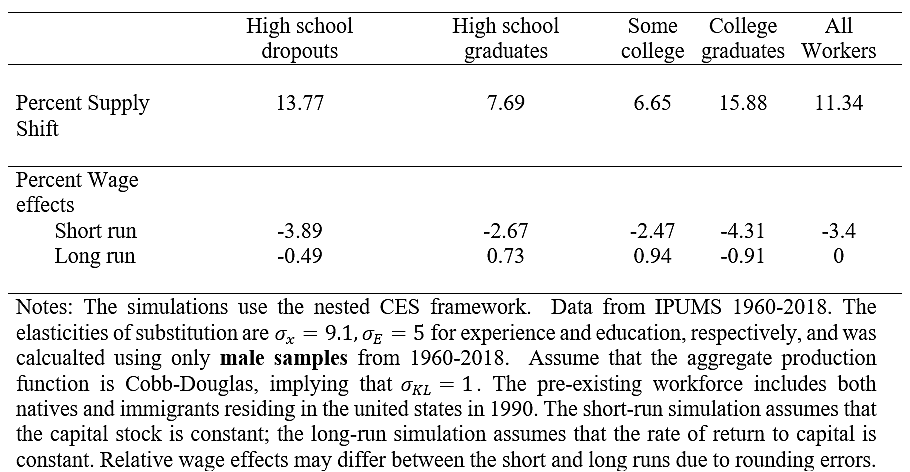

Table 1 shows our results for how immigration affected the relative wages of workers. There was a 15.88 percent increase in the supply of college-educated immigrants between 1990 and 2018, measured by their increase in relative work hours. The increase during this period caused the wages of native-born workers to fall by a relative 4.31 percent on average in the short-run. However, the long-run impact is trivial; a 15.88 percent increase in highly skilled immigrants only caused a 0.9 percent relative decline in wages. The long-run impact takes account of the adjustments in the rest of the U.S. economy in response to immigration, mainly how the capital stock grows. The long-run impact is what matters for judging the impact of immigration on the United States.

One thing is important to emphasize here: The regression results show changes in wages relative to other workers. They are not absolute changes in wages. Therefore, it is accurate to say that the relative wages of college graduates fell by 0.9 percent from 1990–2018 due to immigration, but that their absolute wages still rose during the same time. The wages for college educated workers just rose a little less relative to the workers with different levels of education. In other words, this regression provides zero support for the claim that H‑1B workers or other skilled immigrants lowered the absolute wages of skilled Americans.

Table 1

Simulated wage impacts of 1990–2018 immigrant influx on the preexisting workforce

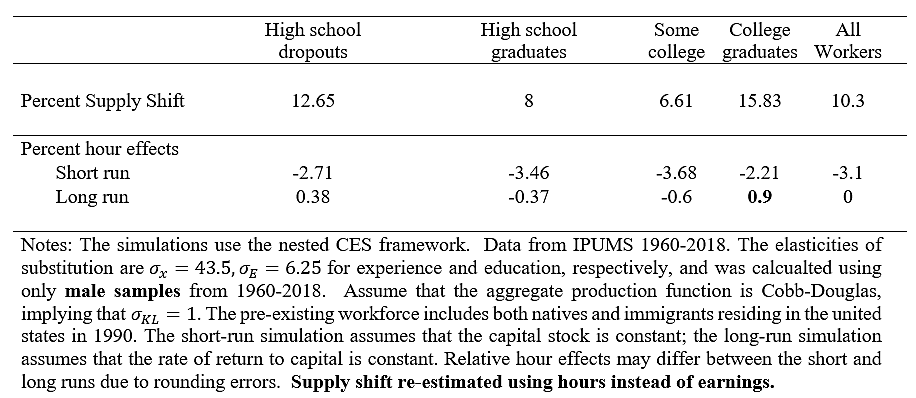

Table 2 shows that college and above educated immigrants increased the relative number of hours worked by college educated Americans by about 0.9 percent. If immigrant workers were displacing American workers, we’d expect to see their relative number of hours decline. Of course, these are relative increases and they don’t show that immigrants displaced native-born American workers at all – just the opposite. Are the DoL wage regulations intended to prevent a slight relative increase in the annual number of hours worked by skilled Americans? We don’t think that’s their legal mandate.

Table 2

Simulated annual hours impacts of 1990–2018 immigrant influx on the preexisting workforce

Conclusion

The DoL justified its IFR to increase the minimum wages for H‑1B migrants by arguing that they 1) reduce the wages of native-born Americans and 2) H‑1B migrants displace native-born American workers. The only peer-reviewed economics articles where they cited hard estimates of the effect of immigrants on the wages and hours worked by native-born American workers is a 2003 article by George J. Borjas.

Using Borjas’ methods from his 2003 paper, his later 2014 book, and changing the period analyzed to when the H‑1B visa was created to the present day, we find that the relative wages and relative hours worked by native-born American workers with a college or above degree were barely affected in the long run and that there is no evidence of an absolute decline in wages. In fact, the relative number of hours worked by Americans slightly increased in response to immigration.

The DoL is not charged with protecting the relative wages of skilled workers or their relative number of hours worked – it is only theoretically charged with protecting their absolute wages. DoL’s citation in the IFR does not provide evidence that skilled immigrants lowered the wages of skilled Americans nor does our update of the evidence.

Since the DoL has such confidence in Borjas’ 2003 paper, we assume that they will be very interested in this analysis that uses Borjas’ methods to examine how native wages and hours worked have been affected by skilled immigrants like those who arrive on the H‑1B visa. Just to be clear, our replication and expansion of Borjas’ work does not mean that we think that methodology is the best to examine how immigrants affect wages, but it is the methodology most likely to be of interest to the DoL. At a minimum, they should be happy to see the results of Borjas’ research extended to the present. We urge the DoL to consider these findings because they contradict their stated justification for the IFR.

Special thanks to Town Oh who helped considerably with this blog post.