Cato will be hosting a panel discussion on January 28, The Future of Progressive Foreign Policy: 2020 and Beyond, featuring Kate Kizer from Win Without War, Loren DeJonge Schulman from the Center for a New American Security, Dan Nexon from Georgetown University, Adam Mount from the Federation of American Scientists, and Mena Ayazi from the Alliance for Peacebuilding.

To provide some broad perspective for the discussion, we are sharing a slightly updated version of an article we published in the November/December issue of the German magazine, Internationale Politik. In it we use speeches and campaign literature from the candidates to discern their foreign policy perspectives. Through our efforts we identified three broad clusters within the Democratic Party that we call traditional liberal internationalist, millennial liberal internationalist, and progressive. The challenge for Democrats, as we discuss below, is to determine which vision is the right one for the post-Trump era…

The recent Democratic debate was the first to showcase foreign policy in a meaningful way. The candidates grappled with questions about the role of Commander-in-Chief, the confrontation with Iran, whether to keep troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, and broader questions of military intervention. Though foreign policy hasn’t played a huge role in the Democratic race so far, international affairs are poised to play a central role this fall. Even without the Ukraine scandal, Trump’s erratic and unpopular record as a statesman provides an opening for Democrats to score points on foreign policy in 2020, but only if they can articulate a new vision that resonates with the American public.

Even before Trump’s election in 2016 foreign policy thinkers were beginning to realize that American grand strategy had to change. After more than fifteen years of war in Afghanistan and the Middle East Americans enthusiasm for foreign adventures had expired, and many observers believed that public support for the traditional American leadership of the liberal international order had expired along with it. The big question was: what would come next?

To most of the Washington foreign policy establishment, Trump’s embrace of “America First” suggested the most terrifying answer possible to this question. Instead of steady American leadership, free trade, a robust system of alliances, and intervention in hot spots around the globe, Trump’s vision relied on unilateralism, protectionism, and withdrawing from America’s endless wars. To say Trump’s election sent shock waves through foreign policy circles in the United States is an understatement.

As Trump nears his fourth year in office, however, it turns out that the public has not embraced his “America First” vision. In fact, Trump has single-handedly pushed public support for international engagement and free trade to near record highs. Since Trump took office, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs finds that Americans are seven percentage points more likely to support global engagement, six percentage points more likely to support the Iran deal and Paris Climate Accords, ten percentage points increase for support for NAFTA, and support for alliances with Japan, South Korea, and NATO are at their highest level since polling began. The result is that Democrats have an opportunity to respond not only to Trump but to provide an updated strategy for dealing with 21st century challenges.

The problem is that Democrats have not yet developed a consensus around that new vision, whatever it might be someday. Since the 2016 campaign candidates and foreign policy experts have been waging a slow but steady, behind-the-scenes battle to define the future of Democratic foreign policy. Though most Democrats can agree on several things like how disastrous Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris Climate Treaty was, or how poorly Trump has treated America’s allies, or how harmful his cozying up to autocrats has been, Democrats have not yet provided a definite answer to at least six important questions:

- Should the United States continue to pursue primacy, attempting to control events around the world, or should it accept that the world is becoming more multipolar and seek to do less abroad?

- Should the United States continue to rely heavily on military intervention, or should it use non-military tools of foreign policy to deal with terrorism, civil war, and other issues?

- Should the United States pursue a foreign policy aimed at spreading liberal values, such as human rights and democracy, or is such an approach contrary to the American national interest?

- Should the United States embrace multilateralism and enhance alliances and international institutions, or should it pursue a more unilateral foreign policy?

- Should the United States seek to strengthen and expand the global system of free trade, or instead pursue a nationalist and protectionist trade policy?

- Should America partner with China and accept a growing Chinese sphere of influence in Asia, or should it attempt to confront, contain, and undermine Chinese power?

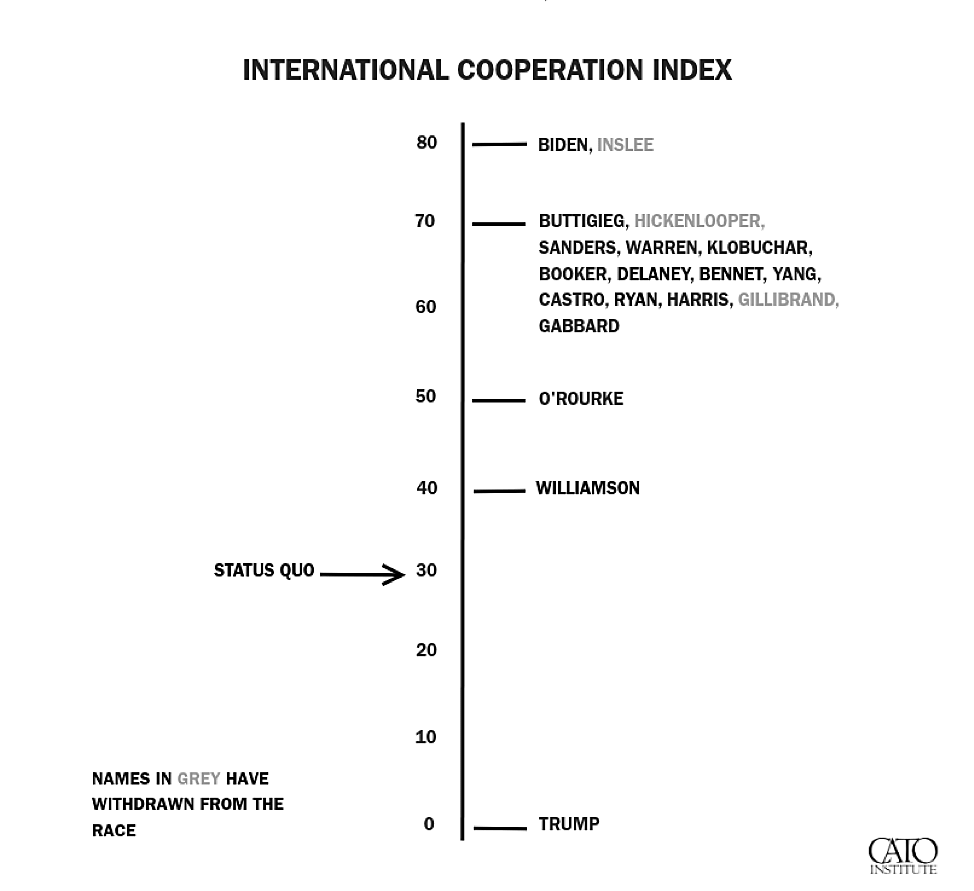

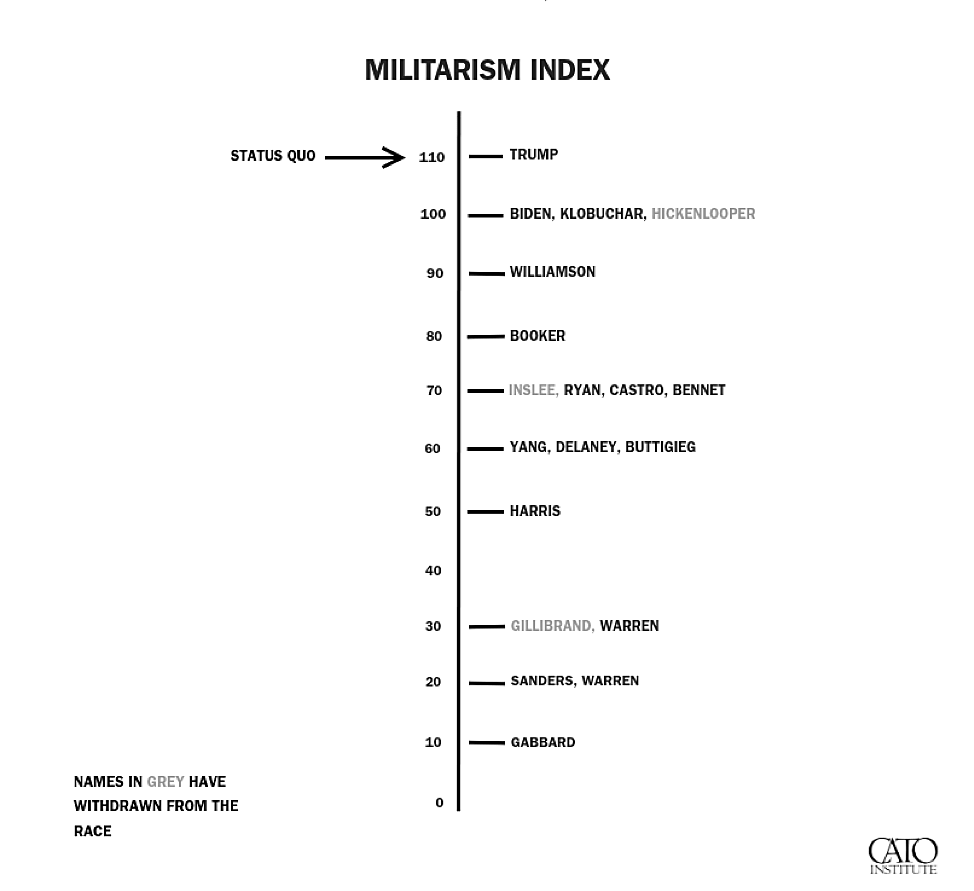

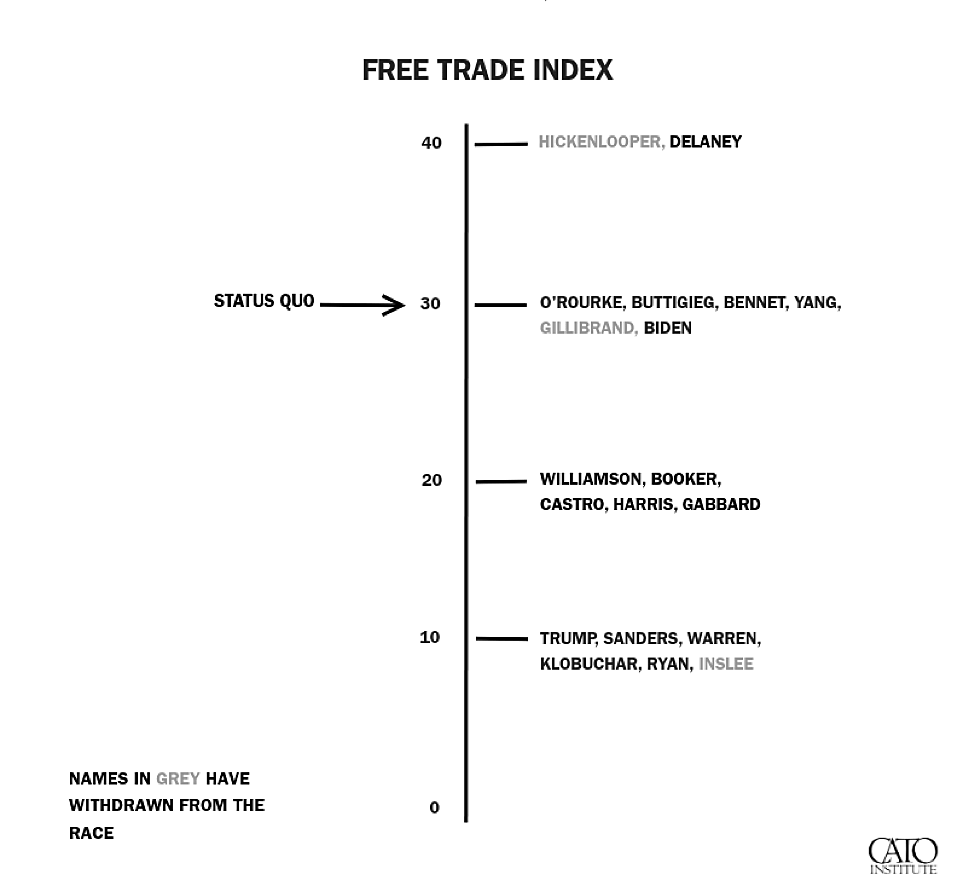

To determine where the Democrats stand today we assessed the eighteen most serious candidates’ positions on nineteen different issues. These issues include things like what the United States should do in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, whether the United States should intervene militarily in North Korea, Iran, Venezuela, Ukraine, or Yemen, and how the United States should deal with both China and the war on terror. We also examined candidate positions on how ambitious and active American foreign policy should be, the importance of alliances and international agreements like the Paris Climate Treaty, and support for free trade agreements as well as the trade war with China.

To identify the candidates’ views we reviewed the candidates’ speeches, websites, sound bites in media coverage, their answers to foreign policy questions in the debates, as well as other efforts by organizations like the Washington Post and the Council on Foreign Relations to summarize their views on the issues.

Our general approach for each issue was to ask whether the candidate’s position was roughly in line with current policy and, if not, in what direction it differed. For military issues we asked whether a candidate was taking a more or less hawkish position than the status quo. We asked whether the candidate favored more or less international cooperation on a range of issues. And we assessed whether candidates were more or less supportive of free trade than current policies.

Though this approach simplifies things a good deal, it allows us to make use of the available information, which is relatively scarce for certain issues and several candidates. This scoring system also allowed us to provide each candidate with an easy-to-understand score for militarism, embrace of international cooperation, and support for free trade. Figure One below summarizes the results of this exercise, illustrating both where candidates stand relative to current American policies and also to one another (warning: these figures were made before several candidates dropped out).

Figure One. 3 Dimensions of Democratic Foreign Policy View

The numbers make it all look very scientific, but it’s important not to push our data too far. After all, most of the candidates have not produced a fully imagined foreign policy doctrine, nor has foreign policy taken center stage at any point so far in the campaign. Some candidates may have remained noncommittal in order to make themselves attractive as a vice presidential running mate. We have undoubtedly missed some important nuances and some candidates may articulate positions different from the ones we have captured here.

The analysis nonetheless helps us identify broad patterns. First, in relation to President Trump, all of the Democrats are less hawkish (though to varying degrees), more inclined toward international cooperation (with very little variation), and only slightly more supportive of free trade. None of these findings are surprising, but they do bolster our confidence that our approach to measuring candidate positions makes sense.

Competing Camps of Democratic Foreign Policy

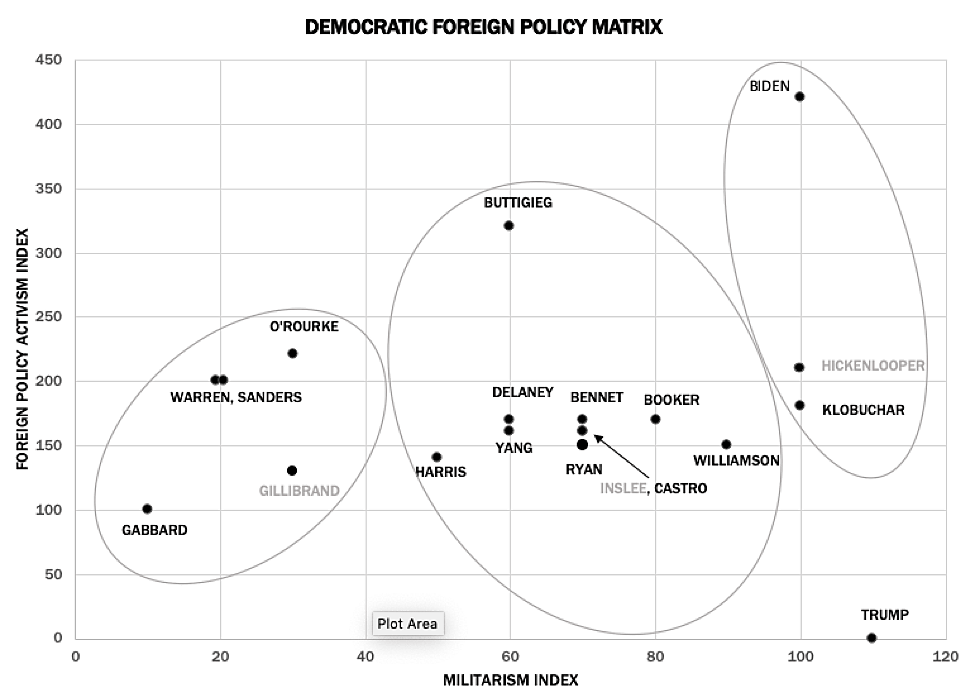

The second and more interesting pattern emerges from focusing on the issues that divide the Democrats. As Figure One shows, all Democrats embrace the need for international cooperation in a general sense. The two main issues dividing them into competing factions today are 1) how forcefully should the United States attempt to exert global leadership, and 2) what role should the use of military force play in American foreign policy?

As Figure Two reveals, when we array the Democrats across the dimensions of militarism and foreign policy activism, we can identify three camps competing to define next generation Democratic foreign policy.

Figure Two. Democratic Foreign Policy Matrix

The traditional liberal internationalists

The first of these is what we call the traditional liberal internationalist camp and comprises the status quo wing of Democratic foreign policy. This camp includes candidates who score high both on militarism but also on the broader index of foreign policy activism, which we determined by how often a candidate has called for doing more than the status quo on an issue, whether the issue is trade, cooperation, or military focused, and by factoring in any explicit statements they have made about the role of American leadership in the world.

The animating principle of the traditional liberal internationalist camp has not changed much

over time. Its advocates believe that the United States remains the “indispensable nation” and has the responsibility to defend the liberal international order and to intervene around the world – through diplomacy as well as by military force – to resolve international problems like climate change, to promote regional stability, to prevent humanitarian tragedies, and to contain the rise of peer competitors like China.

This camp has long dominated both the Republican and Democratic parties, and its members have included George W. Bush and Barack Obama as well as Hillary Clinton. Former Vice President Joe Biden now carries the flag, ranking at the top of the group on both the militarism and cooperation scales and advocating energetic American leadership abroad. Biden’s fellow travelers in this camp include Senator Amy Klobuchar from Minnesota and Dan Hickenlooper, the former governor of Colorado.

Biden has made it clear that if he is elected, he would abandon the inward-looking aspects of Trump’s “America First” foreign policy. On a page from his web site aptly titled “American Leadership,” Biden argued that the United States must take “immediate steps” to “once more place America at the head of the table, leading the world to address the most urgent global challenges.”

And despite the fact that Biden, like all of the other Democrats, has called for ending the “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Iraq, his campaign rhetoric makes it clear that he fully supports the continued pursuit of military primacy, embraces the global war on terrorism, and views the use of military force as an essential foreign policy tool.

The Millennial liberal internationalists

In the middle of the matrix we find the largest group of candidates in a cluster that we call the Millennial liberal internationalists. This group of candidates represents a generational shift between older Democrats who continue to embrace the traditional notion of American exceptionalism and younger Democrats who seem more comfortable with a framework of shared global leadership.

Though the older candidates like Biden, Sanders, and Warren currently lead the pack, these younger candidates clearly sense that the days of traditional foreign policy are numbered. Pete Buttigieg, the 38-year old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, is technically the only member of the Millennial generation in the race, but he is also the candidate who has spent the most time articulating what this vision might look like. In a major foreign policy speech earlier this year, Buttigieg noted that “…we face not just another presidential election, but a transition between one era and another….I believe that the next three or four years will determine the next 30 or 40 for our country and the world.”

On a policy level, the Millennial liberal internationalists tend to have less ambitious visions and, perhaps most importantly, they exhibit less enthusiasm for the use of military force than their older colleagues. As Andrew Yang argues, “America is the beneficiary of the international world order we helped establish throughout the twentieth century. That said, we have deluded ourselves into thinking that we are capable of doing things that we are not, sometimes at a terrible cost to ourselves and others. My first principles concerning foreign policy are restraint and judgment — we should be very judicious about projecting force and have clear goals that we know we can accomplish.”

Progressive internationalism

Finally, on the left side of the matrix we can identify the progressive foreign policy camp, championed most energetically by Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, but also including former Representative Beto O’Rourke, Senator Kristin Gillibrand, and Representative Tulsi Gabbard. Thanks to the success of Bernie Sander’s 2016 campaign and the increasing prominence of progressives in the Democratic Party since the 2018 midterm elections, the progressive foreign policy camp has generated a good deal of momentum of late.

The clearest thread connecting the members of the progressive wing is distaste for the use of military force. The most dovish of this group is Tulsi Gabbard, who argues that the United States needs a new foreign policy that “stops wasting our resources, and lives on regime change wars, and redirects our focus and energy towards peace and prosperity for all people.” In a similar vein, Elizabeth Warren articulated a common progressive critique of American foreign policy when she wrote that “we have allowed the imperial presidency to stretch the Constitution beyond recognition to justify the use of force, with little oversight from Congress. The government has, at times, defended tactics, such as torture, that are antithetical to American values.”

But though the lack of militarism is the most obvious factor that distinguishes this camp from the other two, the most important differences are actually the progressive camp’s idealism and its attempt to link domestic and foreign policy with a unifying thread. The result is that even though there is a good deal of overlap between the policy positions of the progressives and many of the other Democrats, the animating forces of progressive foreign policy and some of its ultimate aims are quite different.

Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, in particular, have articulated foreign policy visions that embrace vigorous American leadership while placing much heavier emphasis on promoting American ideals. They promise much more active American efforts to defend the liberal international order, for example, as well as the promotion of democracy in the face of rising authoritarian challenges. As one observer said of Sanders’ platform, ““It’s a vision in which international economics would be subordinated to a vision of political relations and human rights that would be as big a departure from Clintonism as Trumpism, just in a different direction.”

And in recognition that Trump’s America First rhetoric has struck a chord on Main Street, both Sanders and Warren have attempted to justify foreign policy activism by connecting it to domestic economic concerns. As Warren has written, “Policymakers promised that open markets would lead to open societies. Instead, efforts to bring capitalism to the global stage unwittingly helped create the conditions for competitors to rise up and lash out.” Sanders concurs, arguing that, “we see a growing worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy, and kleptocracy” and that the United States needs to “take into account the outrageous income and wealth inequality that exists globally and in our own country.”

Looking Ahead

This snapshot of the competing Democratic visions raises two important questions. First, assuming one of these Democrats becomes the next president, how far can we trust this analysis to predict his or her future foreign policy choices? Second, which of these will generate the most support from the American public?

Sadly, for foreign policy analysts the predictive power of exercises like this is relatively limited. Rarely do four years pass without events derailing the best laid plans of an administration. George W. Bush, recall, took office in 2001 having argued on the campaign trail that the United States should resist nation building and military intervention abroad.

But even if events did not intrude, there is simply an enormous amount of inertia in American foreign policy, reflected in international institutions and alliances, in domestic politics and public opinion, and in the worldviews of national security professionals. The “Blob” as President Obama called the foreign policy establishment, dominates public foreign policy debates and its members occupy almost all of the important roles in foreign policy making. This has made it difficult for presidents to pursue foreign policies that deviate from traditional liberal internationalism. President Trump has met tremendous backlash whenever he has threatened to chart a more “America First” path, dampening his ability to make big changes. Democrats promoting more radical departures from the status quo like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, or Tulsi Gabbard, would very likely face similar difficulties.

The last question is how well these competing visions are playing with the public. Though Biden leads in most of the polls, his foreign policy is the least appealing to most Democrats, and to young Americans more generally. Research has shown that younger Americans remain committed to cooperative forms of international engagement, but are far less supportive of defense spending and the use of military force than older Americans. In a recent poll, for example, just 44 percent of Millennials felt that maintaining superior military power should be a critical U.S. foreign policy goal, compared to 64 percent of Baby Boomers and 70 percent of the Silent Generation.

The shift from militarism is easily understood. Younger Americans have spent their formative years and early adulthood watching – and fighting in – lengthy, unsuccessful military interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. Unlike their grandparents, they did not experience the heady aftermath of World War II when the United States enjoyed incredible economic and political dominance. Coming of age after the end of the Cold War, neither Millennials nor members of Generation Z have a real awareness of the role military strength played in the successful containment strategy of the Cold War. If they were aware, they’d have also noticed that the United States rarely used military force after the Vietnam debacle and still won the Cold War in 1991. Simply put, to young Americans, war has looked like a poor strategy. As a result, they do not share their elders’ confidence in America’s ability to use military force to pursue national interests effectively.

This intergenerational shift favors both the Millennial liberal internationalists like Pete Buttigieg and the progressive internationalists like Sanders and Warren, at least to a point. A red flag for progressives, however, is the way both Sanders and Warren have recast foreign policy as an extension of domestic debates over economic and social policy. To win middle-class votes, both Sanders and Warren have decried unfair trade deals, kleptocracy, global inequality and the influence of multinational corporations.

Though these are important issues, they are also potential justifications for fruitless and expensive efforts to reshape the world. And just as American military power has failed – dramatically and at staggering cost — to reshape the Middle East over the past 18 years, so too would American economic and diplomatic power fail to reorganize the world to the tastes of the progressives in the Democratic Party.

In short, the danger is that in their search for a motivating principle for the future of U.S. foreign policy, Democrats may propose big ideas that sound nice but will instead promote more misguided U.S. activism under a new heading. Instead, the Democrats’ best bet to win public support, especially from the next generation, is to identify what current U.S. responsibilities — from the ongoing forever wars in at least eight countries to longstanding treaty commitments to militarily defend more than 60 nations abroad – should be abandoned and which must be maintained for the 21st Century.

A special thanks to Sally Huang for compiling and coding the data and to Lauren Sander for creating the graphics.