Louisiana and the Netherlands are engaged in a battle against rising seas. To combat the encroaching ocean, both are dredging up vast amounts of sand to construct barriers along their respective coastlines. As a recent article in the Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate shows, however, the Dutch are doing so at a fraction of the cost Louisiana is paying.

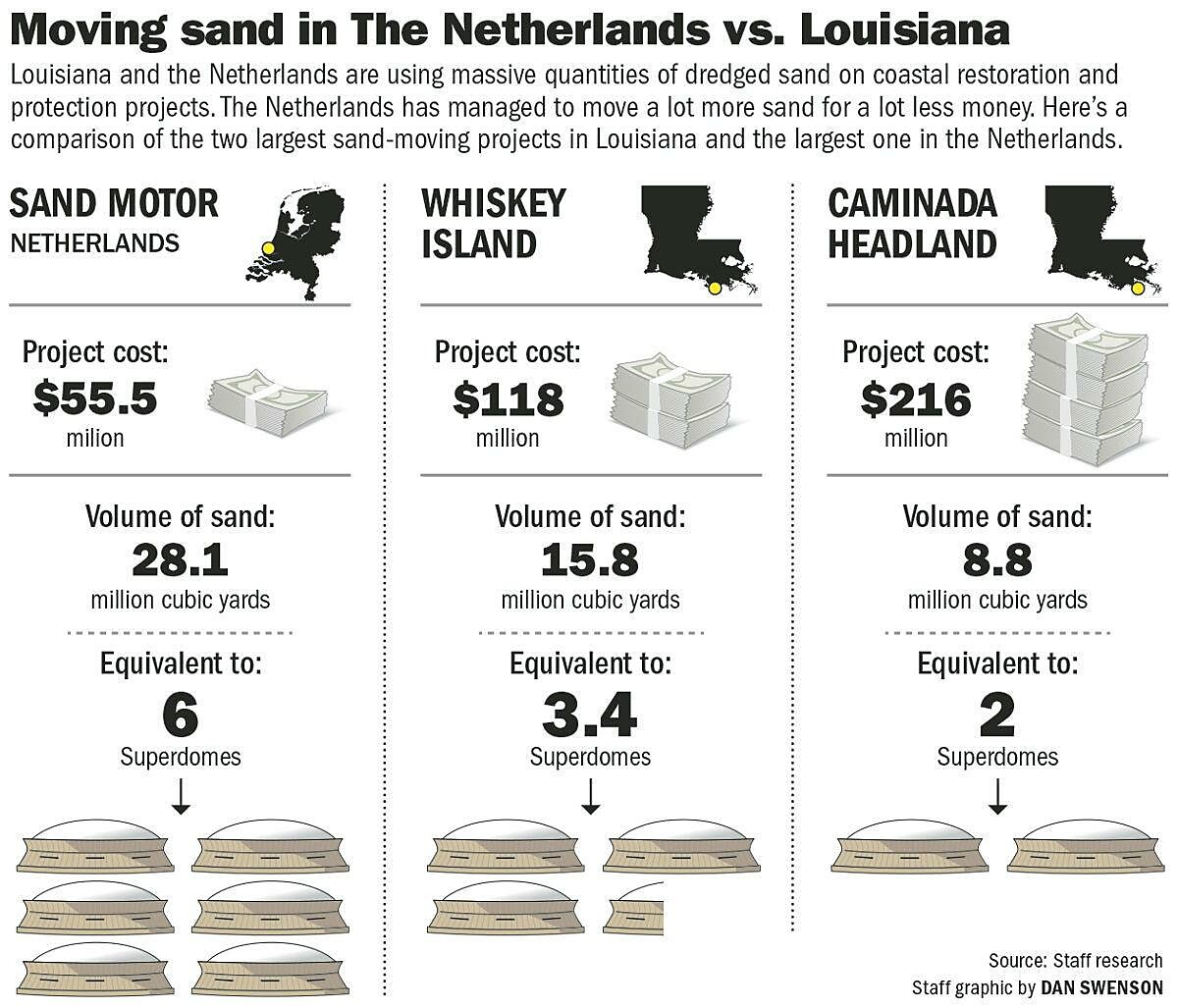

Louisiana’s biggest beach rebuild was on Whiskey Island, a slender, uninhabited island on the edge of Terrebonne Bay. Completed in 2018, the project spent $118 million dredging and spreading more than 15.8 million cubic yards of sand — enough to fill the Superdome three times.

The [Dutch] Sand Motor [project] was completed for about half the money and managed to move nearly two times as much sand.

The comparison is even more unfavorable for another celebrated beach rebuild, the Caminada Headland project of 2017. Caminada’s 13 miles of restored beach protect the oil shipping hub Port Fourchon and La. 1, the only hurricane evacuation route for Grand Isle and other communities. It cost $216 million, nearly four times as much as the Sand Motor. Yet it moved just 8.8 million cubic yards of sand, the equivalent of two Superdomes to the Sand Motor’s six.

This graphic supplied by the publication is illuminating:

So why the stark difference in costs? Louisiana officials interviewed were largely left scratching their heads. One offered up distance as a possible culprit, noting that sand for Whiskey Island had to be transported four miles further than the Sand Motor project. But this explanation fails to satisfy. As the Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate points out, on a per-mile basis the Dutch were still moving sand for half the cost.

Rather than distance, the publication offers another reason: protectionist U.S. maritime laws. More specifically, the 1920 Jones Act and Foreign Dredge Act of 1906.

Vast cost differences are all too common when U.S. dredging projects are compared with ones in other countries, including the Netherlands and Belgium — low-lying nations that export dredging services around the world.

But Belgian and Dutch firms can’t offer their services in the U.S. Two pieces of legislation — the Foreign Dredge Act of 1906 and the Jones Act — effectively banned foreign companies from dredging in U.S. waters. All dredges must be U.S.-built, U.S.-operated and U.S.-crewed. Changes to the Jones Act in 1988 added yet another requirement: American ownership of all barges transporting dredged sand.

The purpose of restricting foreign dredges was to protect U.S. companies and spur the growth of the private dredge fleet, but it’s had the effect of creating a small, closed market that benefits a handful of U.S. operators while making coastal protection and restoration projects far more expensive.

A small market indeed. As the article notes, a mere four firms are responsible for about 98 percent of all private sector U.S. dredge work. It further points out that only five firms in the country possess hopper dredges—vessels capable of both dredging sand and transporting it—and their combined capacity is less than one-third that of a single Dutch dredging firm, Van Oord. Van Oord’s fleet alone includes eight hopper dredges with capacities larger than the biggest U.S. hopper dredge, the Ellis Island. Van Oord’s biggest hopper dredge, the Vox Máxima, has a capacity nearly three times larger (31,387 m3 versus 11,315 m3).

U.S. dredgers themselves have essentially conceded their limited capacity. According to the Dredging Contractors of America, the addition of just two vessels in 2018 caused the capacity of the U.S. hopper dredge fleet to increase by a stunning 34 percent.

The reason for these differences is no mystery. American dredgers largely confine their operations to the U.S. market while European dredgers operate around the world. That is to say, they operate at a much smaller scale. The largest U.S. dredging firm, Great Lakes Dredge and Dock, notes in its most recent annual report that it is the only U.S. dredging service provider with “significant international operations.” Even then, however, such operations over the prior three years only accounted for an average of 13 percent of the company’s dredging revenues.

Why compete abroad when a protected market beckons at home?

A limited market and limited ambitions make for limited capabilities. As Mark Roelofs, Van Oord’s director of dredging for North and South America says of the company’s huge hopper dredges, “You need a big market size to have that, and the world is our market.”

With their larger fleets and larger vessels to meet the demands of a global market, foreign dredgers can unlock economies of scale that U.S. dredgers can only dream about. That, in turn, means lower costs. According to the Times-Picayune/New Orleans Advocate, Van Oord estimates that, even with the use of U.S. crews and support vessels, the company could perform large U.S. dredge projects three times faster and at 60 percent of the cost of U.S. dredging firms.

This is the story of U.S. maritime protectionism writ large. Instead of competing internationally, the U.S. maritime sector lies cloistered in a captive market (in 2014, exports accounted for a mere 4.6 percent of U.S. shipbuilding revenue). A small, less productive industry means higher costs for maritime services and harm to the U.S. economy. But this protectionism—like all such measures—is failing not only the U.S. economy but the very sector it was meant to benefit. Instead of U.S. firms playing a leading international role as in other transportation-related sectors such as autos and aerospace, the U.S. maritime sector lies debilitated and withered. The seemingly sweet nectar of a captive market has proven to be a trap.

That these laws are maintained is largely due to a national security justification that becomes more absurd by the day. Laws such as the Jones Act and Foreign Dredge Act are typically justified as necessary to protect U.S. shores, but as Louisiana shows they literally make it more difficult to defend them. A better symbol for the counterproductive effects of these laws will be hard to find.