Gentlemen may cry default, default, but there will be no default. (With apologies to Patrick Henry.)

Once again the media are full of talk about dysfunction and default, as the partial government shutdown threatens to linger until the federal government hits the limit of its borrowing capacity, possibly on Oct. 17. The parties in Congress are still far apart on passing a budget bill to keep the government running, and Republicans are also promising not to raise the debt ceiling without some spending reforms.

If in fact Congress doesn’t raise the ceiling by mid-October—or by November 1 or so, when the real crunch might come—then the federal government would be forbidden to borrow any more money beyond the legal limit of $16.699 trillion. But it would still have enough money to pay its creditors as bonds come due. The government will take in something like $225 billion in October, but it wants to spend about $108 billion more than that. You see the problem. If it can’t borrow that $108 billion—to cover its bills for one month—then it will have to delay some checks.

Now the U.S. Treasury isn’t full of stupid people. Back in 2011, when the debt ceiling of $14.3 trillion was about to be reached, the Washington Post reported:

The Treasury has already decided to save enough cash to cover $29 billion in interest to bondholders, a bill that comes due Aug. 15, according to people familiar with the matter.

You can bet they’re making similar plans today.

Back in that summer of discontent I talked to a journalist who was very concerned about the “dysfunction” in Washington. So am I. But I told her then what’s still true today: that the real problem is not the dysfunctional process that’s getting all the headlines, but the dysfunctional substance of governance. Congress and the president will work out the debt ceiling issue, if not by October 17 then a few days later. The real dysfunction is a federal budget that doubled in 10 years, unprecedented deficits as far as the eye can see, and a national debt bursting through its statutory limit of $16.699 trillion and heading toward 100 percent of GDP.

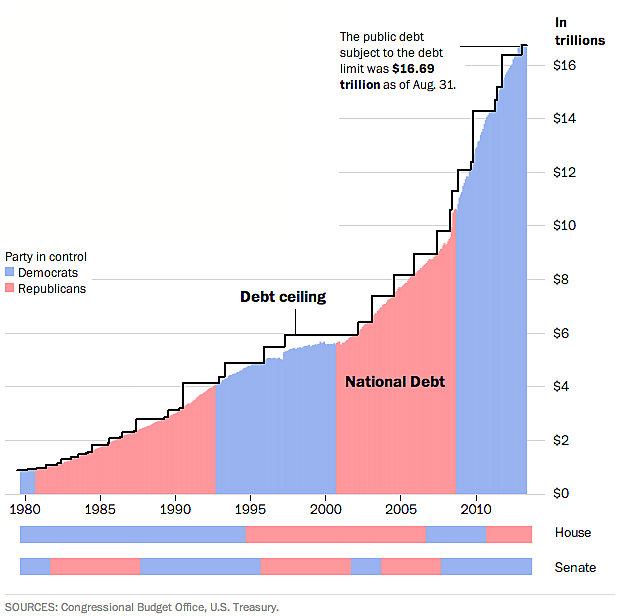

We’ve become so used to these unfathomable levels of deficits and debt—and to the once-rare concept of trillions of dollars—that we forget how new all this debt is. In 1981, after 190 years of federal spending, the national debt was “only” $1 trillion. Now, just 33 years later, it’s headed past $17 trillion. Traditionally, the national debt as a percentage of GDP rose during major wars and the Great Depression. But there’s been no major war or depression in the past 33 years; we’ve just run up $16 trillion more in spending than the country was willing to pay for. That’s why our debt as a percentage of GDP is now higher than at any point except World War II. Here’s a graphic representation of the real dysfunction in Washington:

Those are the kind of numbers that caused the Tea Party movement and the Republican victories of 2010. And many Tea Partiers continue to remind their representatives that they were sent to Washington to fix this problem. That’s why there’s a real argument over raising the debt ceiling. It’s going to get raised, but many of the younger Republicans are determined to set a new course for federal spending in the same bill that authorizes another yet more profligate borrowing.

And where did all this debt come from? As the Tea Partiers know, it came from the rapid increase in federal spending over the past decade:

Annual federal spending rose by a trillion dollars when Republicans controlled the government from 2001 to 2007. It rose another trillion during the Bush-Obama response to the financial crisis. So spending every year is now twice what it was when Bill Clinton left office a dozen years ago, and the national debt is almost three times as high.

Republicans and Democrats alike should be able to find wasteful, extravagant, and unnecessary programs to cut back or eliminate. And yet many voters, especially Tea Partiers, know that both parties have been responsible for the increased spending. Most Republicans, including today’s House leaders, voted for the No Child Left Behind Act, the Iraq war, the prescription drug entitlement, and the TARP bailout during the Bush years. That’s why fiscal conservatives have become very skeptical of bills that promise to cut spending some day—not this year, not next year, but swear to God some time in the next ten years. As the White Queen said to Alice, “Jam to-morrow and jam yesterday—but never jam to-day.” Cuts tomorrow and cuts in the out-years—but never cuts today.

If the “dysfunctional” fight that has sent the establishment into hysterics finally results in some constraint on out-of-control spending, then it will have been well worth all the hand-wringing headlines. The problem is not a temporary mess on Capitol Hill and not a mythical default, it’s spending, deficits, and debt.