In the wake of the mistrial of police officer Michael Slager accused of shooting and killing unarmed Walter Scott as he ran away, a new Cato Institute/YouGov survey of public attitudes toward the police finds a 38-point gap between white and black Americans’ perception that police are too quick to resort to deadly force.

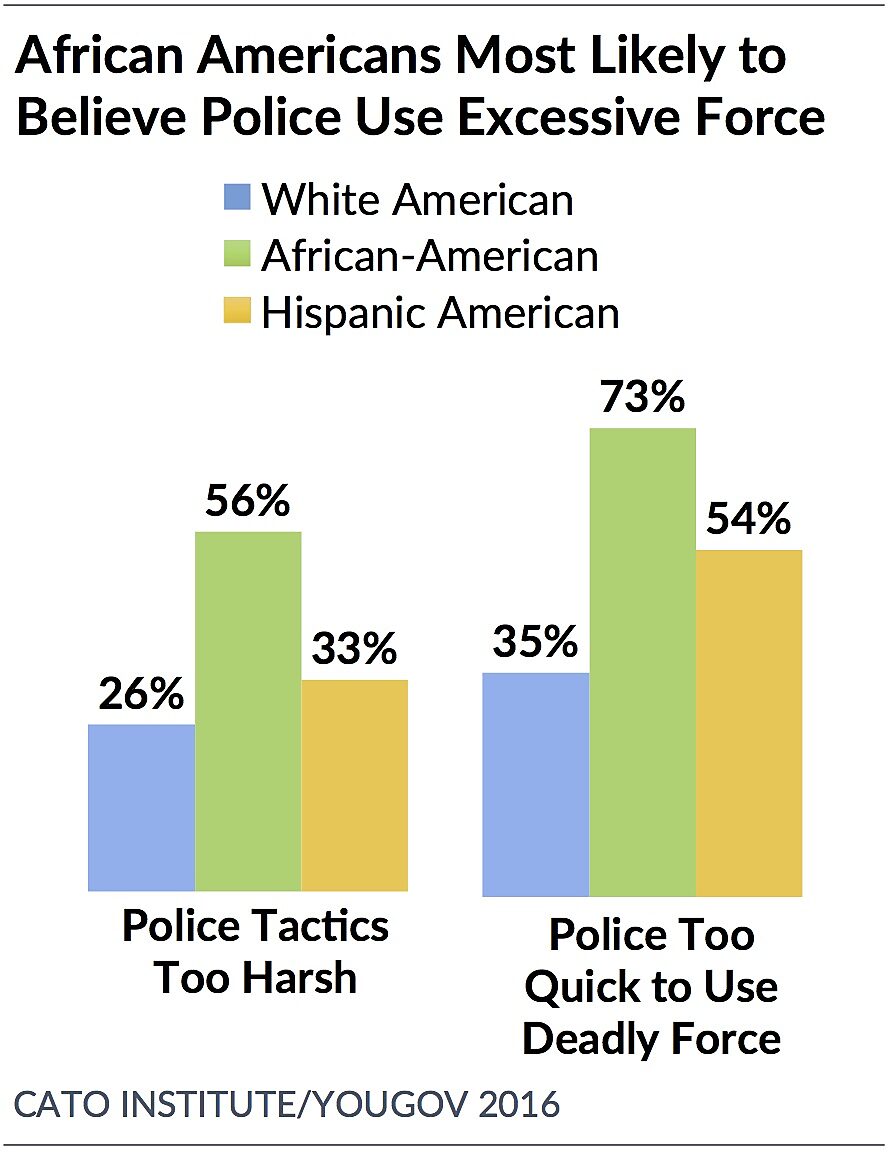

Nearly three-fourths (73%) of African Americans and 54% of Hispanics believe the police are “too quick to use deadly force,” compared to 35% of white Americans. Instead, 65% of white Americans believe police resort to lethal force “only when necessary.”

When it comes to police tactics overall, black Americans (56%) are more likely to think they are “too harsh” compared to white (26%) and Hispanic (33%) Americans. Majorities of whites (67%) and Hispanics (58%) believe police generally use the right amount of force for each situation.

Find the full public opinion report here.

Is the Justice System Impartial?

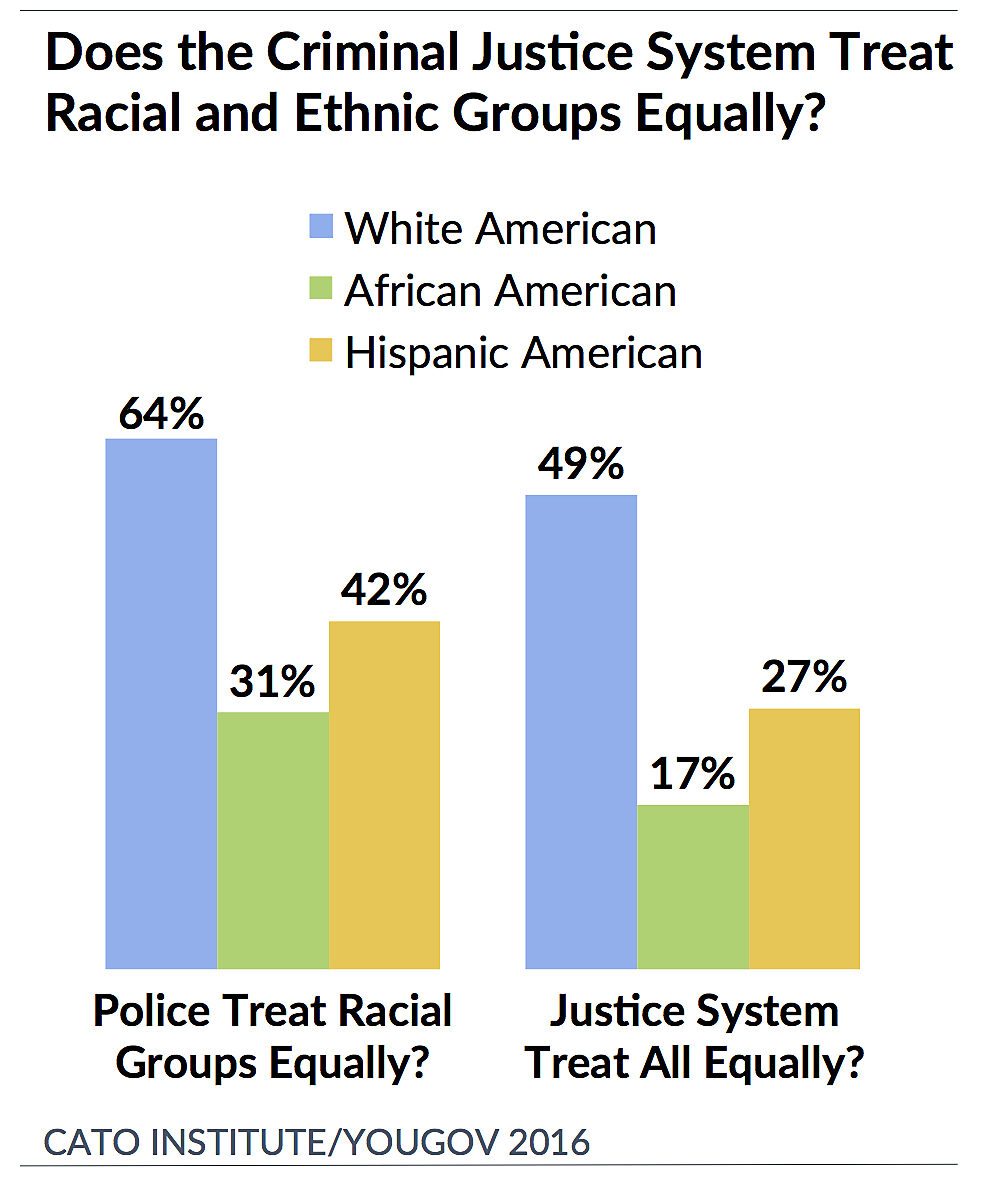

Only 17% of African Americans believe the criminal justice system treats all Americans equally and only 31% are highly confident their local police department treats all racial groups impartially. Whites are 32 points more likely to believe the justice system treats everyone equally (49%) and a solid majority (64%) are confident their local police are impartial. Hispanics fall in between with 27% who think the justice system and 42% who believe their local police treat everyone the same. Among all Americans, only 42% think all are treated equally by the justice system but 56% are highly confident their local police department treats everyone equally.

Are Police Trustworthy and Held Accountable?

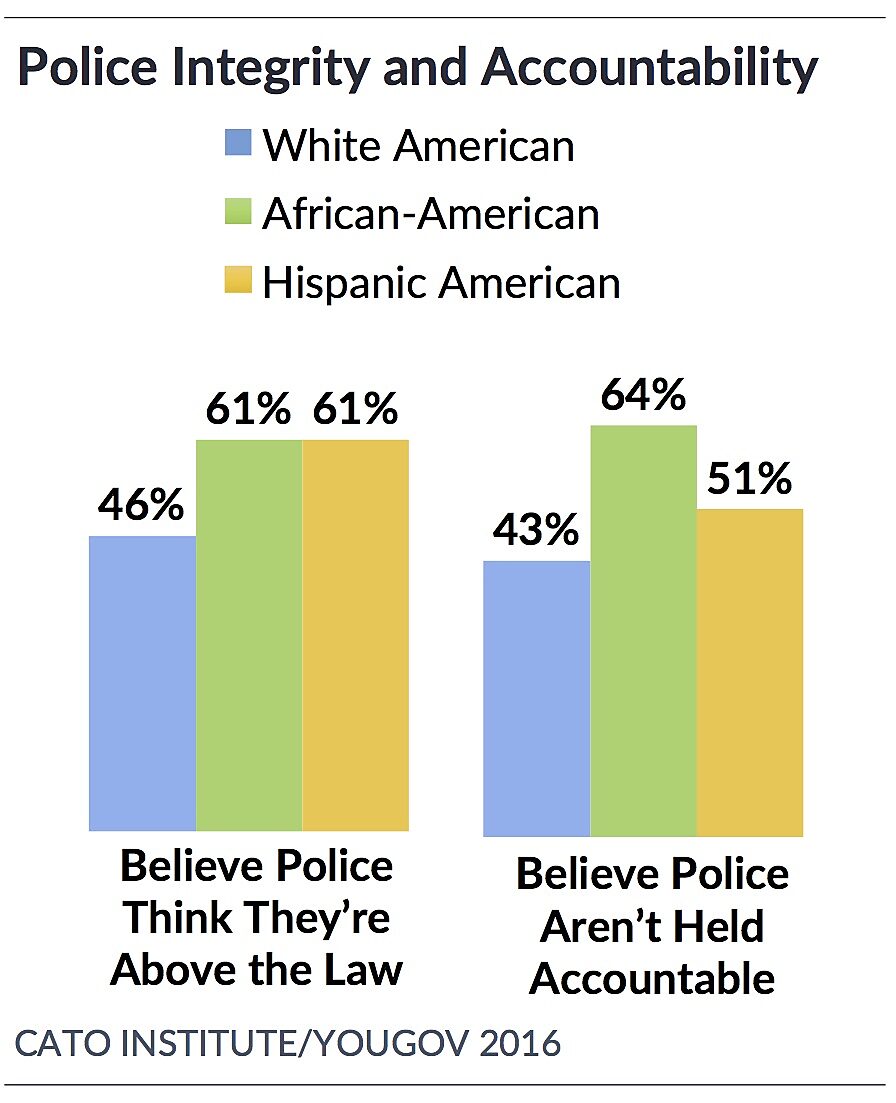

Strikingly high numbers of whites (46%), blacks (61%), and Hispanics (61%) think that “most” police officers “think they are above the law.” Overall, nearly half (49%) of all Americans worry that police think the law doesn’t entirely apply to them.

Nearly two thirds (64%) of black Americans and a majority (51%) of Hispanic Americans believe police are “generally” not held accountable for misconduct when it occurs. This is 21 points higher than the 43% of white Americans who also share this view. Instead, a majority (57%) of whites think police are generally brought to account.

Are Police Effective?

African Americans (41%) and Hispanics (41%) are twice as likely as white Americans (29%) to say they are “extremely” or “very” worried about crime. Furthermore black Americans (41%) are more than twice as likely as whites (17%) or Hispanics (15%) to say they know someone who was murdered.

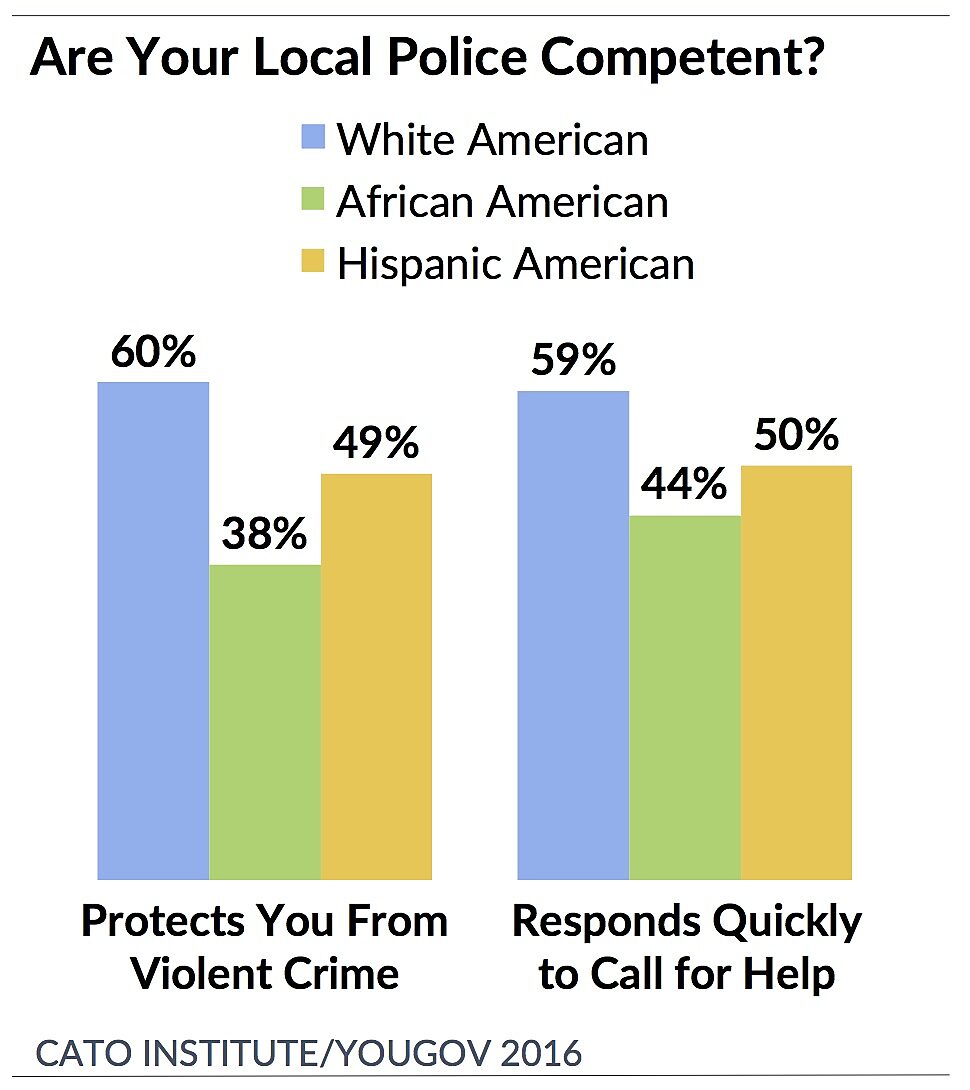

Despite more salient fears over safety, only 44% of African Americans are highly confident their local police department responds quickly to a call for help. White Americans are 15 points more confident (59%) in their local police to come quickly if needed. In a similar pattern, white Americans are about 20 points more likely than black Americans to give their local police high marks for protecting them from crime (60% vs. 38%) and enforcing the law (64% vs. 44%). Hispanics fall in between with about half who give their police high marks for enforcing the law, protecting them from crime, and responding promptly.

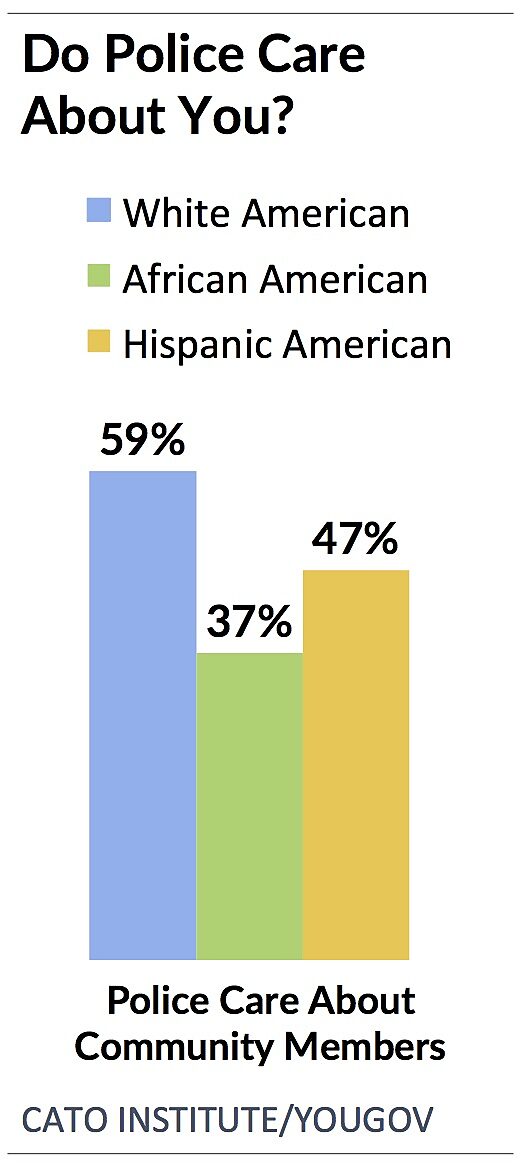

Do the Police Care About You?

Only 37% of African Americans are highly confident their local police department cares about the people they serve. White Americans (59%) are far more confident that their local police cares. A little less than half of Hispanic Americans (47%) agree.

Are the Police Courteous?

White Americans (62%) are 19 points more likely than African Americans (43%) and 13 points more likely than Hispanic Americans (49%) to rate their local police departments highly for being courteous.

White, Hispanic, and Black Americans Report Different Experiences with Police

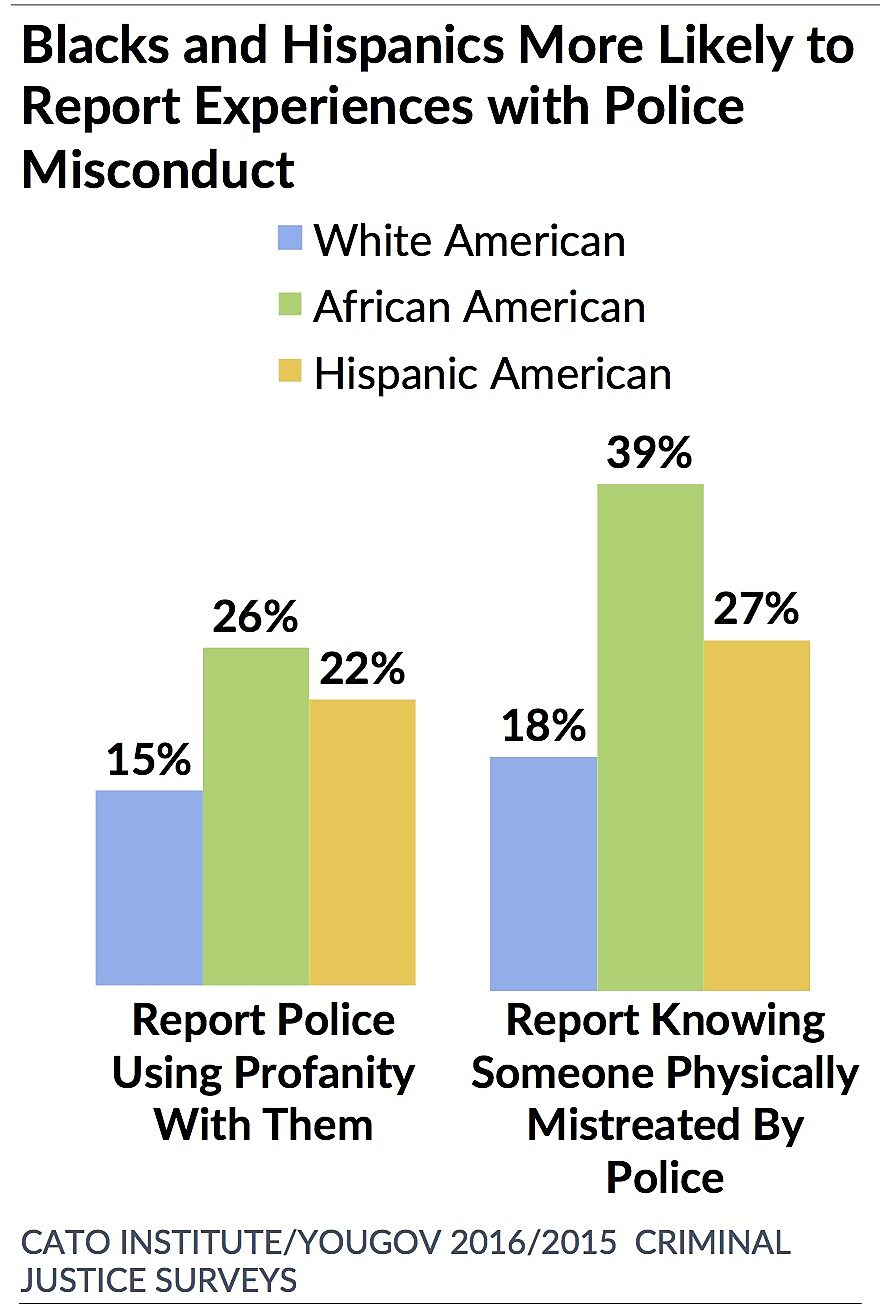

Most Americans have personally had positive experiences with the police but those who have experienced verbal and physical misconduct are disproportionately black and Hispanic.

African Americans are nearly twice as likely as whites to say a police officer swore at them.

About a quarter of African Americans (26%) and Hispanics (22%) report a police officer personally using abusive language or profanity with them compared to 15% of white Americans. The study also found some evidence that suggests whites who are highly deferential toward the police are less likely to report experiences with police profanity, whereas blacks and Latinos who are highly deferential do not report similarly improved treatment. [1]

African Americans are about twice as likely as white Americans to know someone physically abused by police. Thirty-nine percent (39%) of African Americans know someone who has been physically mistreated by the police, as do 18% of whites and 27% of Hispanics.

Higher-income African Americans report being stopped at about 1.5 times the rate of higher-income white Americans. In contrast, lower income African Americans report being stopped only slightly more frequently than lower income white Americans.

African Americans (50%) are also about 30 points less likely than whites (70%) and Latinos (66%) to report being satisfied with their personal police encounters over the past 5 years.

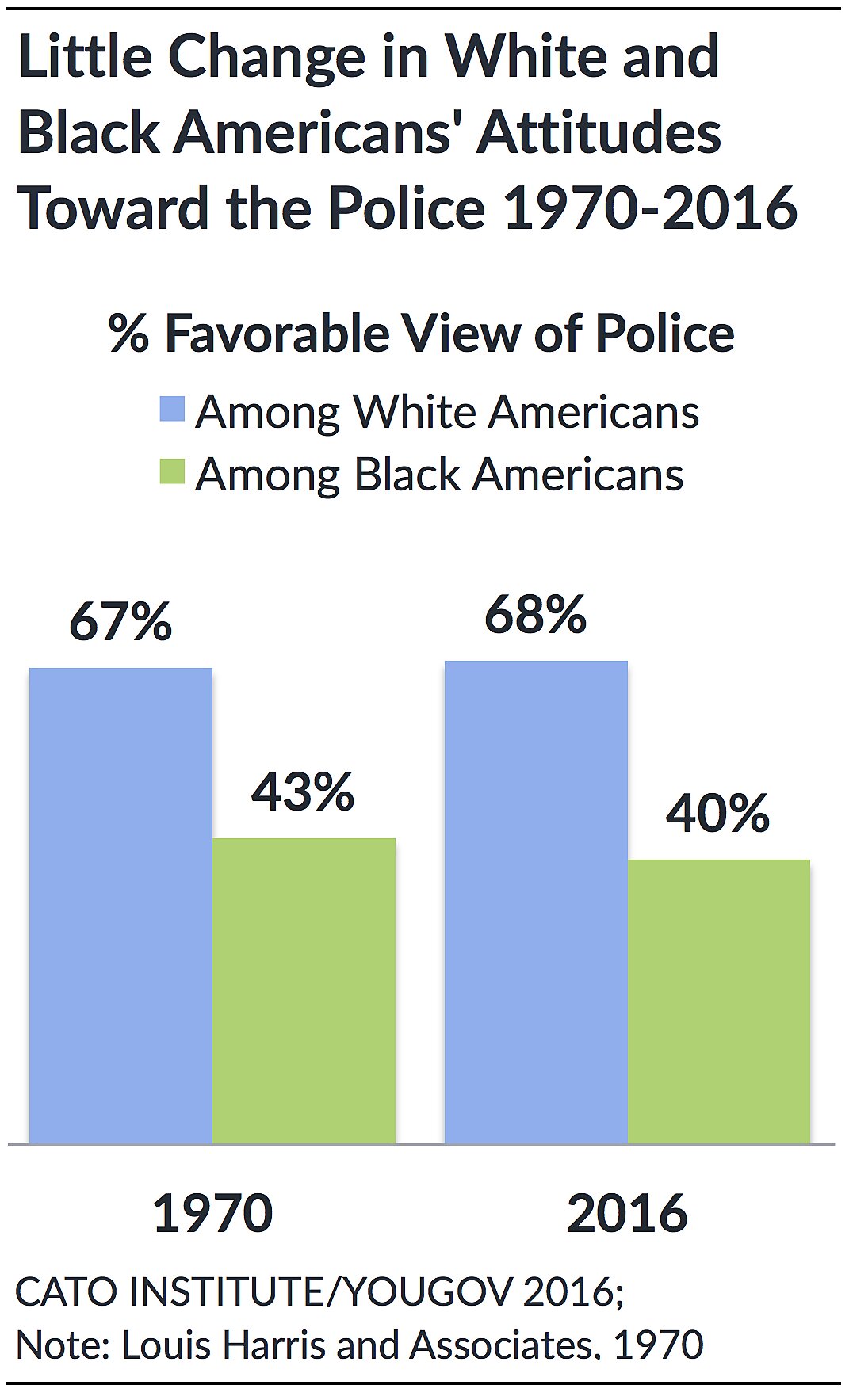

Favorability Gap Toward Police Has Changed Little Over Past 50 Years

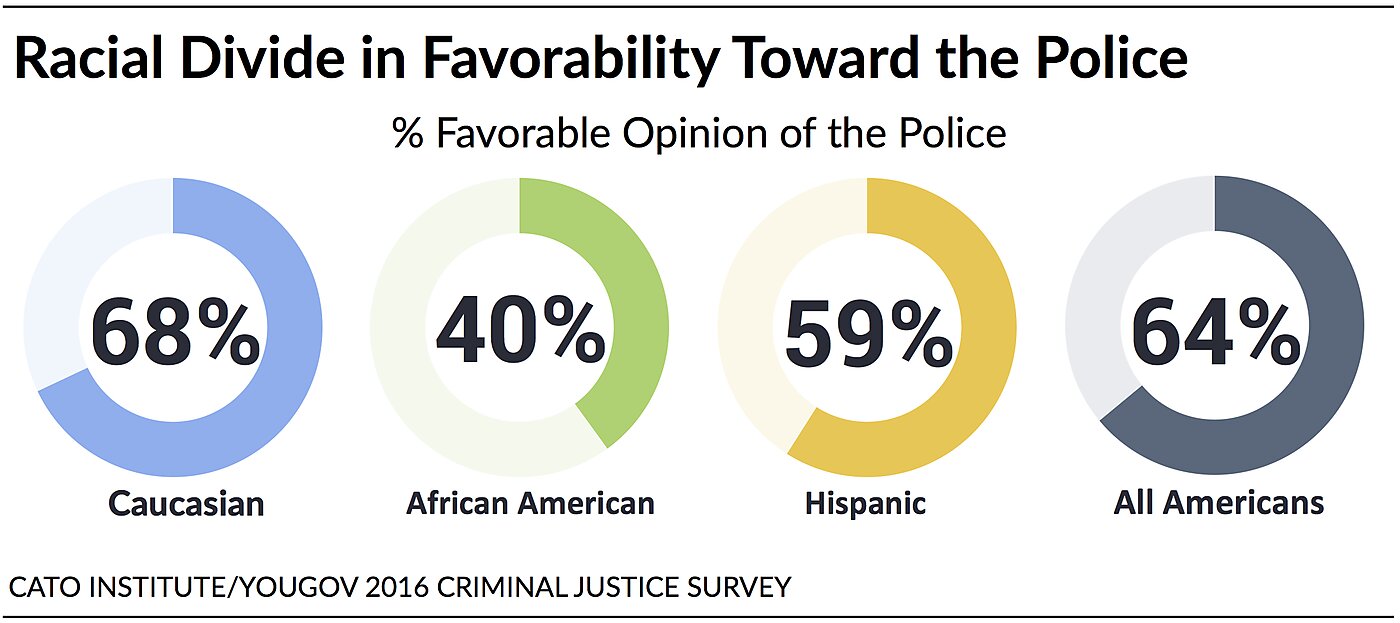

Taking these results together, it comes as little surprise that there is a wide racial gap in favorability toward the police. Only 40% of black Americans have a favorable view compared to 68% of white Americans. Hispanic Americans fall in between with 59% who share a positive view of the police.

What is particularly surprising, however, is that these numbers haven’t changed much since 1970 when 67% of white Americans and 43% of African Americans had a favorable view of the police—nearly identical to today’s numbers.[2]

Perceptions of Police Use of Force and Racial Bias Are Likely Key

In sum, African Americans and Latinos are less confident than whites that the police use appropriate force, are impartial, are competent, have integrity, are professional, care about them, and are held accountable.

While each of these perceptions matter, statistical tests reveal two perceptions are likely key drivers of African Americans’ confidence in the police: 1) perceptions of excessive use of force and 2) perceptions of racial bias.

These tests indicate that after controlling for the effects of these perceptions, African Americans are no less likely than whites or Hispanics to have favorable views of the police. (See Appendix J). In other words, results suggest if we were able to equalize or reduce the belief that the police use excessive force or are racially biased, the race gap in attitudes toward the police could very well disappear.

Certainly, we also want to improve perceptions of police effectiveness, accountability, integrity, and empathy. However, finding ways to minimize the amount of physical force police need to use and improving perceptions of police impartiality may prove most efficacious in restoring public confidence.

Americans Are Not “Anti-Cop”

It’s important to point out: although some groups have less positive views of the police, no group is “anti-cop.” You might expect a person who is “anti-cop” to want fewer police in their community.[3] But 9 in 10 Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity, oppose reducing the number of police officers in their communities. Instead, about half of blacks, whites, and Hispanics favor maintaining present levels and more than a third say their community needs more officers. Activists who call for “abolishing” or “defunding” the police may get media attention but are rare, and do not represent the views of very many people. Furthermore, 6 in 10 black, white, and Hispanic Americans all think police have “very dangerous jobs.”

Why We Should Care About the Confidence Gap in Police Performance

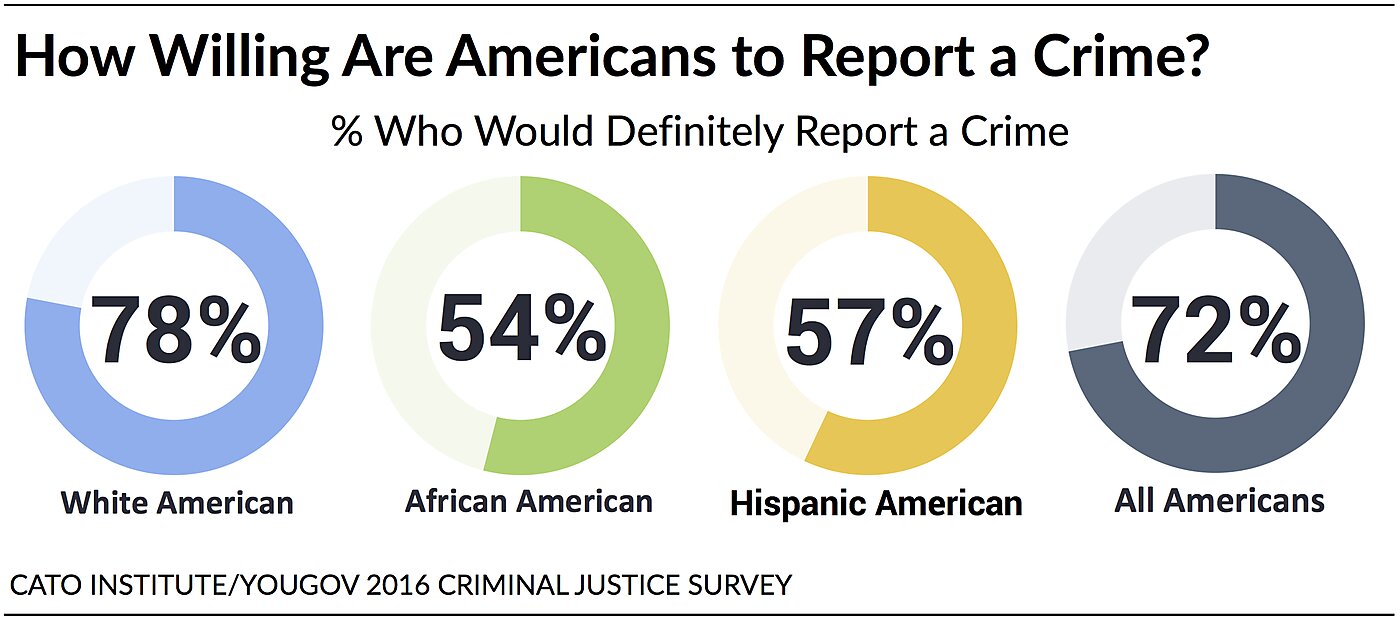

Confidence gaps in police come with consequences. Individuals with less favorable views of the police are less likely to “definitely” report a crime they witness. For instance, African Americans and Hispanics are more than 20 points less likely than white Americans to say they’d definitely report a crime. Among African American men making less than $30,000 a year, fewer than half are as confident they would do so.

Effective policing depends on police and communities working together in a symbiotic relationship based on mutual respect and trust. The police are best able to safely and effectively serve and protect their communities when the residents freely cooperate with the police. And citizens are more willing to cooperate and help the police when they have confidence in them.[4] Moreover, public confidence in the police bolsters their legitimacy and by extension compliance with the law.[5]

Thus, regardless of one’s own experiences and views of police, these perception gaps alone merit our attention. It is important to improve relationships between police and communities they serve, or risk further eroding the legitimacy of the police and by extension the rule of law more generally.

Policing in America helps in this endeavor by carefully examining Americans’ perceptions of and experiences with law enforcement to help uncover why Americans think differently about the police. It also investigates and finds broad support for reforms that many believe can help improve police-community relations. You can find the full report here.

For public opinion analysis sign up here to receive Cato’s upcoming digest of Public Opinion Insights and public opinion studies.

The Cato Institute/YouGov national survey of 2000 adults was conducted June 6–22, 2016 using a sample drawn from YouGov’s online panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. YouGov uses a method called sample matching, and restrictions are put in place to ensure that only the people selected and contacted by YouGov are allowed to participate. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is +/-3.19 percentage points. The full report can be found here, toplines results can be found here, full methodological details can be found here.

[1] Data in this section come from the combined June 2016 and November 2015 national surveys (N=4000), which offer greater precision and smaller margins of error for subgroups. See the Survey Methodology for more information.

[2] Louis Harris and Associates Study No. 2043, 1970, cited in Michael J. Hindelang,” Public Opinion Regarding Crime, Criminal Justice, and Related Topics.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 11 (1974):101–116.

[3] To be sure, advocates of shrinking police departments are not necessarily “anti-cop” either; however, it’s difficult to argue a person is if they do not want to cut the police force.

[4] See Linquiin Cao, James Frank, and Francis T. Cullen, “Race, Community Context and Confidence in the Police.” American Journal of Police 15 (1996): 3–22. Tom Tyler, and Jeffrey Fagan, “Legitimacy and Cooperation: Why Do People Help the Police Fight Crime in Their Communities?” Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law 6 (2008): 231–275; Andrew V. Papachristos, Tracey L. Meares, and Jeffrey Fagan, “Why Do Criminals Obey the Law? The Influence of Legitimacy and Social Networks on Active Gun Offenders,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 102 No. 2 (2009): 397–440; Tom R. Tyler, “The Role of Perceived Injustice in Defendants’ Evaluations of Their Courtroom Experience,” Law & Society Review 18 (1984): 51–74; Tom Tyler, Why People Obey the Law (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006); Jonathan Blanks, “How Pretextual Stops Undermine Police Legitimacy,” Case W. Res. L. Review 66 (2016): 931–946.

[5] Andrew V. Papachristos, Tracey L. Meares, and Jeffrey Fagan, “Why Do Criminals Obey the Law? The Influence of Legitimacy and Social Networks on Active Gun Offenders,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 102, no. 2 (2009): 397–440.