Private schools are the preserves of rich, white people, and if they weren’t around education would be more racially integrated. That’s probably the assumption many people have, and it could be what people reading about a recent Shanker Institute report on segregation in Washington, DC, might have gathered.

“It’s no secret that the District’s public schools are highly segregated, with a recent analysis showing that nearly three-quarters of black students attend schools where they have virtually no white peers,” began a Washington Post story on the Shanker analysis. “But a recent report examines the role that enrollment in private schools, which are disproportionately white, plays in the city’s segregation woes.” Similarly, a story on WAMU—a DC NPR affiliate—intoned: “‘In a very loose sense,’ the authors explain, ‘D.C.’s private schools serve as the segregation equivalent of a suburb within a city.’ That’s because white students in D.C. tend to enroll in private schools.”

So are the city’s private schools really preserves of white people? And are they a big impediment to integration? The answer appears to be “no” to both questions.

Importantly, the Shanker report, while saying that a disproportionate share of private school students are white, also noted that African-American students in private schools had greater exposure to white students than black children in public schools, an indicator that for African-American kids in private schools the racial mix is less isolating. The typical black student in a DC public school (traditional and charter) goes to an institution in which only 3.5 percent of students are white. For the typical black private schooler, the student body is 24.5 percent white.

Those numbers indicate greater exposure to whites for African American private schoolers, but that the latter is not a much higher number also indicates that many African Americans attend private schools that are predominantly minority, which the WAMU story notes at the very bottom: “While there are fewer students of color in private schools, when they do attend private school it’s usually with students who look like them. 65 percent of an African-American student’s peers in D.C. private schools are also African-American.”

Contrary to what many people likely imagine, DC’s private schooling sector is not lily white: private schools serve all sorts of kids. Breaking down the city’s 63 private elementary and secondary schools using National Center for Education Statistics and GreatSchools.org data indicates that almost half—31 schools—serve predominantly minority student bodies, defined as more than 50 percent black and Hispanic. Roman Catholic schools—which have traditions of serving first dispossessed Catholics, then other poor and marginalized groups—disproportionately serve such populations, with 58 percent of Catholic schools doing so. Catholic schools, especially diocesan institutions, also tend to be less expensive than non-Catholic schools, making them more affordable to African Americans and Hispanics, who tend to have lower incomes.

This brings us to a powerful, underlying factor in school selection: where one lives. People typically do not want their children traveling long distances or durations to get to school, and will tend to choose schools—public, private, or charter—fairly close to home.

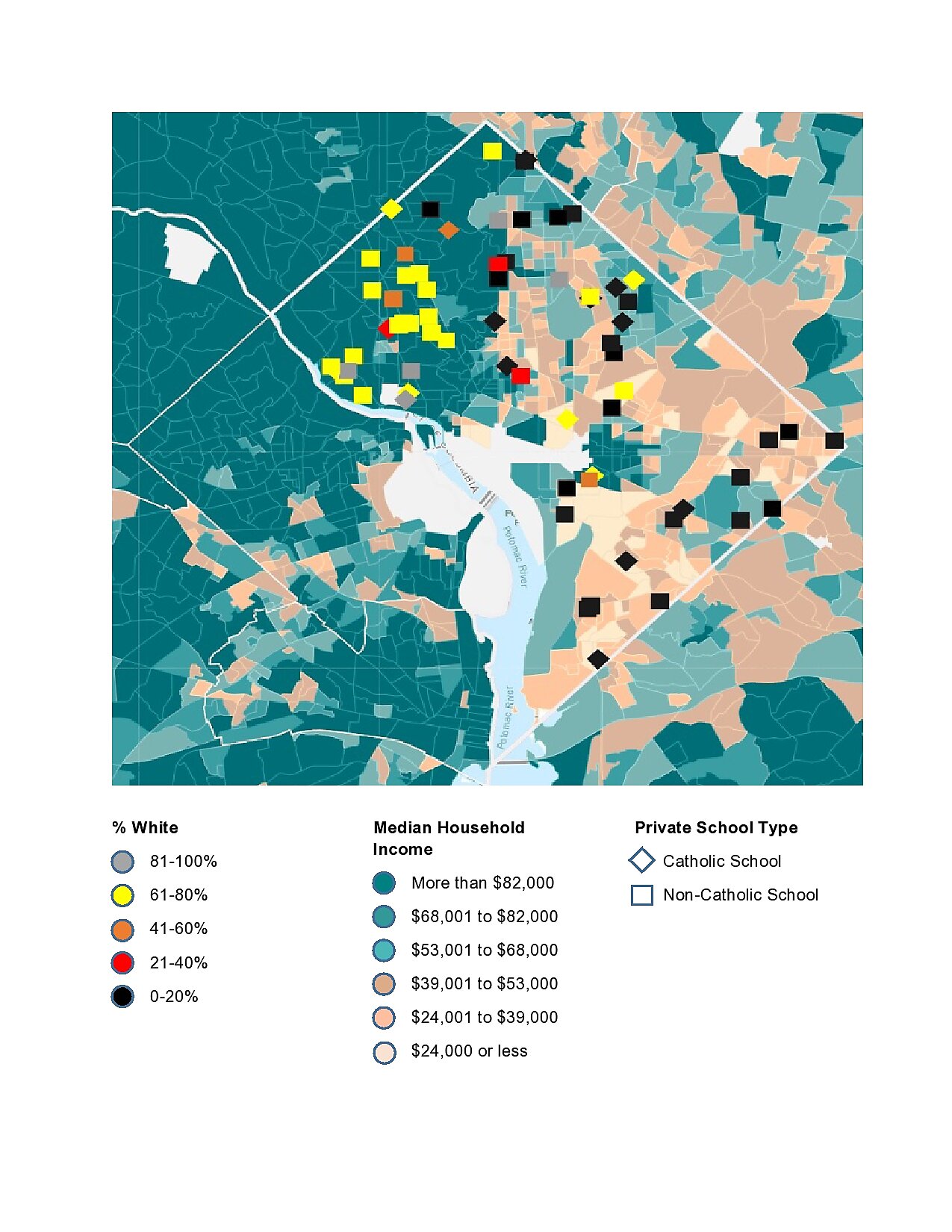

The map below plots the percent white in each DC private school on top of median household income by census tract. (It also indicates Catholic or non-Catholic). What is seen pretty clearly is that the predominantly white private schools are largely found in the wealthier parts of the city, the less white in the poorer. Racial stratification in DC private schools, then, does not appear to be a private school problem, but a wealth and housing issue.

There is one other, even deeper possibility to consider, and the Shanker report notes it: absent predominantly white private schools, many white families might not even be in DC, or they might move to catchment areas with predominantly white public schools. It could be that the ultimate factor in segregation, then, is neither public nor private, wealth, nor housing, but that white people tend to prefer to live with other white people, and for that matter African Americans with other African Americans, and Hispanics with other Hispanics.

That said, private schools may actually have the key ingredient, at least within education, to erode those tendencies. They are free to espouse strong, coherent values and offer unique communities, which could attract diverse students and, via their shared values and school cultures, create new, lasting identities that bridge racial divides. Of course, price would still be a major obstacle, but not if public policy were to move in the direction it should: attach education funds to students and empower families to choose.