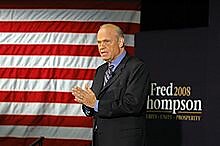

I have a piece running in the Federalist this week on the notion that presidential candidates should campaign “joyfully,” as Jeb Bush ever more desperately insists that he is. It’s not clear why we’re supposed to want joyful candidates, but that seems to be the prevailing norm. Hardly a week goes by without reporters needling the contestants: are you having fun yet? I wrote the column before former Senator Fred Thompson passed away on Sunday, but it occurred to me that his failed 2008 run is a perfect illustration of how perverse the cult of campaign-trail positivity has become.

By almost any measure, Thompson had a full life: a Watergate Committee counsel whose questioning revealed the existence of the White House tapes; U.S. senator from Tennessee; “Law and Order,” “The Hunt for Red October,” “Die Hard 2.” But his short-lived presidential campaign isn’t part of the highlight reel. The Tenneseean put it gently in their obituary: “Mr. Thompson underwhelmed” in his 2008 bid. The press was harsher when Thompson dropped out of the race. “You must show an interest in running for the most powerful office in the world to gain that office,” John Dickerson scolded in Slate, but “The press copies of his daily schedule always looked like they’d been handed out with a couple of the pages missing. The candidate seemed like he might just show up for events in

sweatpants.” “As his hopes cratered,” Politico chided, “the former Tennessee senator increasingly voiced his displeasure with a process he plainly loathed. Thompson’s stump speech became mostly a bitter expression of grievance against what was expected of him or any White House hopeful.” Ha: what a weird old grouch! I mean, the guy’s an actor, and he still couldn’t fake it! What’s wrong with him?

And yet, earlier generations of Americans would have viewed Thompson’s reticence as reassuring. As the political scientist Richard J. Ellis explained in an insightful 2003 article, “The Joy of Power: Changing Conceptions of the Presidential Office,” early American political culture took it as self-evident that anyone who seemed to relish the idea of wielding power over others couldn’t be trusted with it. “Presidential candidates largely stayed home in dignified silence,” he wrote, “ready to serve if called by the people.…Distrusting demagoguery and tyranny, the dutiful presidency demanded dignity, reserve and self-denial from its presidents.”

By the mid-20th century, those cultural expectations had been upended, replaced with a demand for happy warriors with fire in their bellies and joy in their hearts. Changes in the nomination process reinforced the new norms, increasingly favoring boundless ambition and stamina. Campaigning for president “was something I didn’t do well,” Thompson himself reflected in 2014, “You have to about want it more than you want life itself.” But it’s worth asking: what sort of person wants the job that badly? And, are we sure we want that sort of person for the job?

As I wrote in the Federalist:

A latter-day Cincinnatus might put down his plow in the hour of his country’s need; he’s not going to sign up for a two-year ultramarathon of pleading with high-dollar donors, glad-handing his way through primary states, and saying things no intelligent person could possibly believe. Instead, we get the sort of person who wants presidential power badly enough to do what it takes to get it, 16 hours a day, feigning joy all the while.

At least, we should hope it’s feigned. Anyone who approaches “the process” with genuine joy in his heart is a maniac who should be kept as far away from “kill lists” and nuclear weapons as possible.

Years later, one of Thompson’s former aides said he’d have been “a great president, if he didn’t have to campaign for it.” I don’t know about the “great president” bit. I’m increasingly unsure that such a creature is possible. But Thompson’s inability to feign enthusiasm for the process spoke well of him. It suggested that he was psychologically healthy and normal. Those qualities are ruthlessly winnowed out by the modern presidential race, which rewards those with an unhealthy appetite for presidential power and glory. You’ve got to want it to win it, and they want it more.