Over that past couple of months, we have seen an uptick in permanent private school closures that are at least partially due to COVID-19 – 9 in the last 60 days, after just 3 in all of September through December – and we are likely to see many more soon, as schools take stock of enrollment numbers for next year and decide if they will be viable. And who do these closing schools tend to serve? Almost certainly “regular,” or even low-income, families.

From the outset of our tracking we have published the average tuition of closing schools, which currently sits at $7,032. That strongly indicates that these are not typically schools serving, say, the children of presidents. To put $7,032 in context, we spend more than double that – $15,424 per student – in public schools, and according to Private School Review, the average tuition for private schools is $11,173.

To burrow a bit deeper into the character of closing schools, we took a look at the median family income in the census tract for each school on our tracker. Again, the evidence points to the schools in trouble being those that serve ordinary people, not the rich. The median, median family income for the census tracts of schools on our tracker is $75,117. In 2019, the median family income nationally was $88,149.

The private schools on our list are – or were – typically in lower-income communities. They are also typically Roman Catholic. Not surprisingly, as we see on the chart above, which reports average tract median incomes by type of school, Catholic schools tend to skew toward lower-income areas. (Note, however, that other than independent schools, we have very few non-Catholic institutions on the tracker).

What does this mean for public policy?

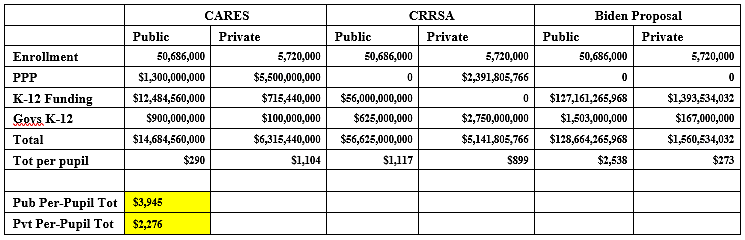

First, while it should not be the concern of the federal government to save private schools, the COVID “relief” Washington is contemplating would put them at an even greater competitive disadvantage than they are already in, since they have to charge tuition and public schools are “free.” By our estimates of enacted and potential aid, public schools would receive $3,945 in assistance per-pupil, and private schools only about $2,276.

If there is to be more federal aid, it should simply follow students.

At state and local levels we need to expand school choice programs. Currently 26 states have legislation to do that, but the road is always rocky as teacher unions, school board associations, and other establishment interests use their large numbers and easy ability to organize to fight choice. On the flip side, the pandemic has made the need for choice increasingly obvious, even among people who have generally been happy with the public schools.

The private schools we are losing are not rich. They are disproportionately low-cost, and in lower-income areas. To help them, policymakers do not need to do something extraordinary. They just need to treat the families that want to use them equally.