Some advocates and policymakers think government should be involved in providing a limited or modest paid leave benefit, just 12 weeks or less. Their support seems implicitly contingent on the expectation that a paid leave entitlement wouldn’t grow, or wouldn’t grow much. But is there any evidence of that?

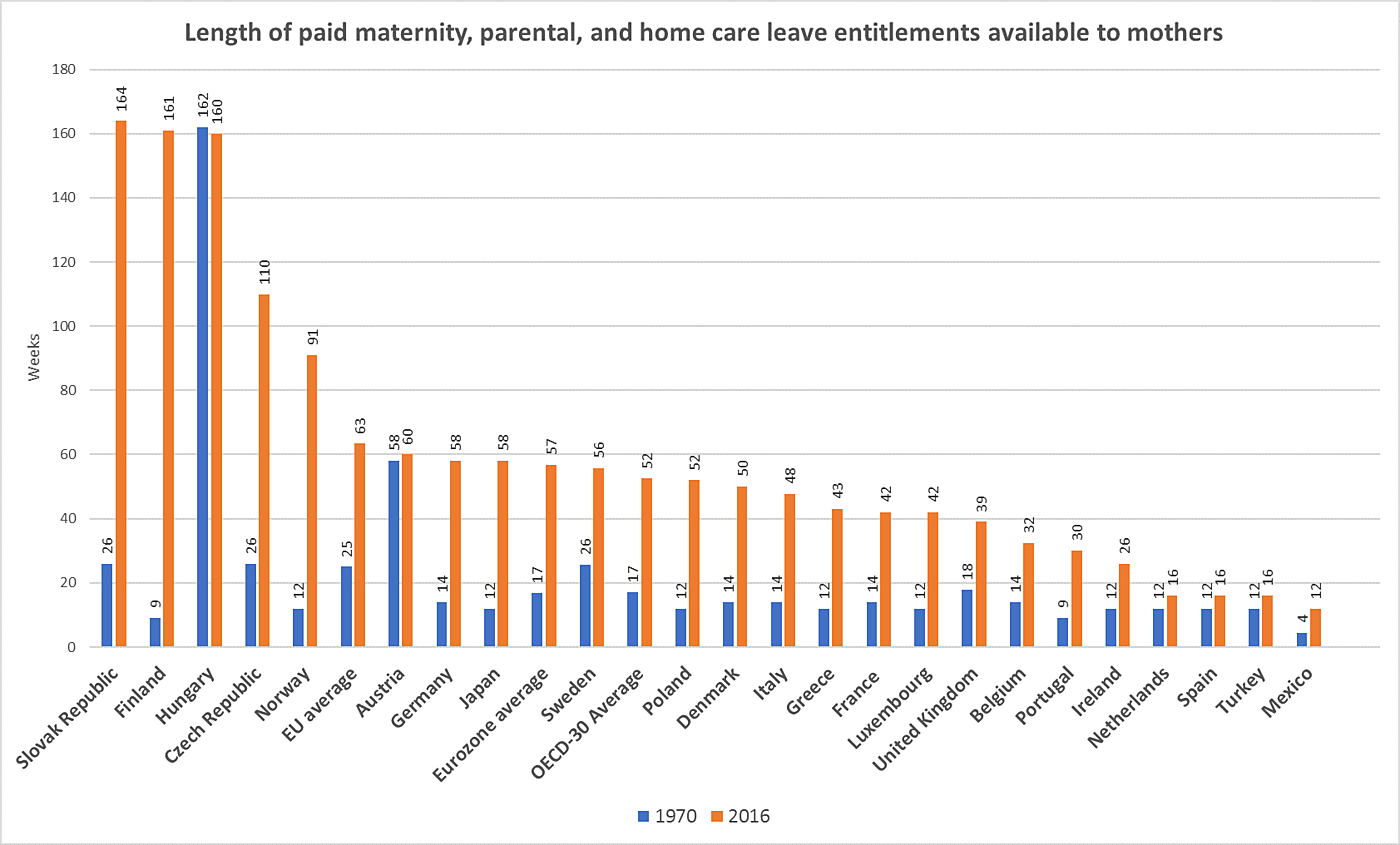

If the trajectories of OECD paid leave entitlements are any indication of the path a new U.S. entitlement would take then the answer is no. All OECD countries except one increased the length of their paid leave benefits substantially over time (see chart).

For example, the average length of paid maternity, parental, and home care leave entitlements in the Eurozone increased from 17 weeks in 1970 to 57 weeks in 2016. That means that the average duration of paid leave entitlements more than tripled over the period. OECD countries at-large follow the same trend.

In fact, the only country that reduced the length of its paid leave entitlement is Hungary. Hungary began with one of the most lengthy paid leave entitlements of any country; 162 weeks in 1970. In subsequent years Hungary reduced the length of that benefit by 2 weeks, to 160 weeks, which isn’t much.

Data source: OECD Family Database

In short, international programs demonstrate that paid leave benefits grow substantially over time, similar to other government entitlement programs. Supporters of government paid leave should be aware that current proposals aren’t likely to stay limited to 12 weeks or less in the longterm.

For more information on paid leave, see the new Cato report Parental Leave: Is There a Case for Government Action? or livestream today’s Capitol Hill event.