In today’s Washington Post Lawrence Summers demonstrates with mathematics that you can’t shrink the federal government — as long as (he doesn’t say) you don’t change the tasks you assign to it. True enough, if the government is still going to engage in “sustained deployments” of our military across the globe, and provide retirement income and health care to tens of millions of people, then the size of government isn’t going to shrink. But surely those are the issues we should be debating.

Michael Cannon below notes another key point in Summers’s argument:

[I]ncreases in the price of what the federal government buys relative to what the private sector buys will inevitably raise the cost of state involvement in the economy. Since the early 1980s the price of hospital care and higher education has risen fivefold relative to the price of cars and clothing, and more than a hundredfold relative to the price of televisions.

I would elaborate on Michael’s response. The fact that “the price of hospital care and higher education” has risen much faster than the cost of other goods is not an exogenous variable. Why do those costs rise so much faster? Because the government purchases them, reducing or eliminating the normal effects of supply, demand, and competition. I wrote about this in a 1994 article reprinted in my book The Politics of Freedom responding to an argument made by the economist William Baumol and the scholar-statesman Daniel Patrick Moynihan:

Moynihan identifies a number of services afflicted with Baumol’s disease: “The services in question, which I call The Stagnant Services, included, most notably, health care, education, legal services, welfare programs for the poor, postal service, police protection, sanitation services, repair services … and others.” He points out that many of those are provided by government and posits that “activities with cost disease migrate to the public sector.”

But maybe he has it backwards. Maybe activities that migrate to the public sector become afflicted with cost disease. The conservative magazine National Review, which, surprisingly, seems to accept Moynihan’s thesis, has inadvertently supplied us with some evidence on this point.

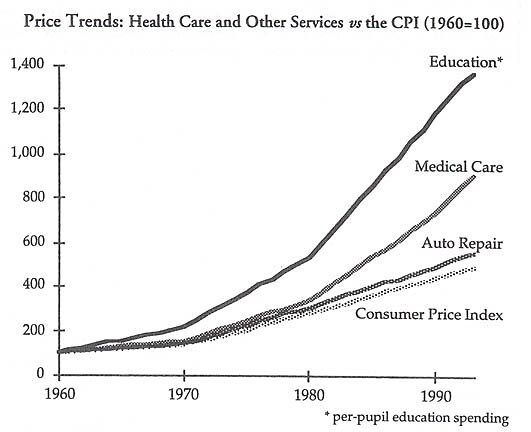

Ed Rubinstein, National Review’s economic analyst, writes, “For more than three decades health-care spending has grown faster than national income.… The trend in health-care costs is no different from that of other services.” He cites education and auto repair as examples. However, the numbers Rubinstein provides don’t support his–or Moynihan’s–point. Look at the accompanying figure.

The cost of auto repair, a service provided almost entirely in the private sector, has barely outpaced inflation. The cost of medical care increased twice as fast as inflation. Government’s share of medical spending increased from 33 percent in 1960, when the chart begins, to 53 percent in 1990. Meanwhile, the cost of education, almost entirely provided by government, increased three times as fast as inflation–despite the constant complaints about underfunded schools.

The lesson is clear: Services provided by government are afflicted with Baumol’s disease in spades. Services provided in the private sector, where people spend their own money, are much less likely to soar in cost.

Medical care is a good area in which to test this theory because over the past 30 years it has been paid for in three different ways: out-of-pocket spending by consumers; insurance payments, mostly provided by employers; and government payments. As out-of-pocket spending declines in importance, medical inflation heats up. And private-sector spending on medical care rose only 1.3 percent a year between 1960 and 1990, while government spending rose more than three times as fast–4.3 percent a year.

When services are provided privately, and consumers can decide whether to purchase them, or choose another provider, or do without, there’s a powerful incentive to improve productivity and keep costs down. Stagnant productivity in government-run services reflects not so much Baumol’s disease as what we might call Clinton’s disease, the notion—even now, in 1994—that government can provide services more efficiently and cost-effectively than can the marketplace.

Now, I think Larry Summers knows this. He knows that when consumers don’t face full costs for services, they tend to consume more of them without worrying about the cost. So he knows that these costs could come down, if only we moved these services into the market, or at least found ways to get consumers directly concerned with costs. He should rethink his claims about the inevitability of more expensive government. These realities are in fact choices, decisions that voters and taxpayers can change.