I recently questioned two connected remarks by Wall Street Journal reporter Richard Rubin that (1) “Each percentage-point reduction in the 35% corporate tax rate cuts federal revenue by about $100 billion over a decade” and that (2) “independent analyses show economic growth can’t cover all the costs of rate cuts.”

That first remark–about each percentage-point reduction in the rate losing $100 billion over a decade–is an interpretation of pages 178–79 from a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on “Options for Reducing the Deficit.”

But the CBO was just talking about raising the corporate rate by one point, not cutting it 10–20 points. That can’t be converted into a rule of thumb because each percentage point reduction in the top corporate tax rate can’t lose the exact same amount of dollars. A percentage point reduction in a 35% rate loses more static revenue than a percentage point reduction in a 30% rate, which loses more than a percentage point reduction in a 25% rate, and so on.

Yet even for a single percentage point, I called the $100 billion 10-year projection a “bad estimate” because it assumes zero change in the economy and zero change in tax avoidance (“elasticity”).

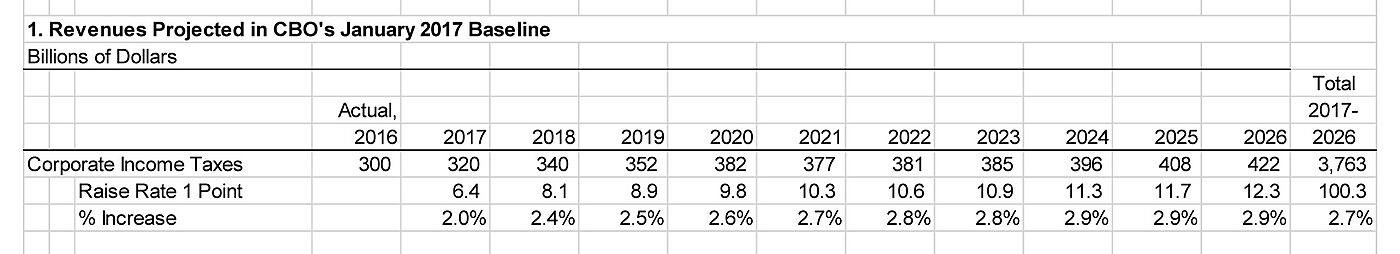

The Table compares the CBO/JCT static estimates of what might happen with a percentage-point increase in the corporate tax rate to their baseline “projections” of what corporate revenues might look like under current tax law, assuming 1.9% GDP growth. The line below the baseline adds static estimates (“from the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation” or JCT) of the revenue gain from raising four graduated corporate tax rates from 15–35% to 16–36%.

The average tax rate is below the top marginal rate because of reduced 15–25% rates on small profits, credits for foreign taxes, deferral of taxes on unrepatriated foreign profits, and deductions for interest and business expenses. Goldman Sachs estimates the average tax as 28% under current law and 24% (not 20%) under the Ryan-Brady tax.

If the average tax is 28% then a 1 percentage point increase in all four marginal rates might be expected to raise static revenue by about 2.8%. Sure enough, JCT claims a 1 percentage point increase in corporate rates would eventually raise revenues by roughly 2.8%, suggesting those estimates entirely static. That is, they assume zero impact on GDP and zero elasticity of taxable income.

Despite publishing these static revenue estimates, the CBO analysis does a good job of explaining why they are seriously flawed. Bad bookkeeping is no substitute for good economics.

What follows is the CBO analysis of the economics of a higher corporate tax rate, with emphasis added in bold:

Increasing corporate income tax rates would make it even more advantageous for firms to organize in a manner that allows them to be treated as an S corporation or partnership…. Raising corporate tax rates would also encourage companies to increase their reliance on debt financing because interest payments… can be deducted…. Moreover, the option [of raising the tax rate] would discourage businesses from investing, hindering the growth of the economy.

Higher rates in the United States influence businesses’ choices about how and where to invest; to the extent that firms respond by shifting investment to countries with low taxes as a way to reduce their tax liability at home, economic efficiency declines…. The current U.S. system also creates incentives to shift reported income to low-tax countries without changing actual investment decisions. Such profit shifting erodes the corporate tax base and requires tax planning that wastes resources. Increasing the top corporate rate to 36 percent (40 percent when combined with state and local corporate taxes) would further accentuate those incentives to shift investment and reported income abroad.

How could all of those changes possibly fail to affect the amount of revenue collected?

Hindering growth of the economy by discouraging business investment reduces revenue. Shifting reported income into other countries and into pass-through entities erodes the tax base and reduces revenue. Increasing debt and other deductible expenses (fancier offices and lunches) reduces revenue. Yet the static revenue estimates in the Table obviously take none of this into account–ignoring both macroeconomic effects of higher tax rates on investment and GDP growth and microeconomic “elasticity” effects on tax avoidance.

Since the CBO explains how and why a higher corporate tax rate has numerous adverse effects on revenues, it follows that a lower corporate tax rate has numerous beneficial effects on revenues. In fact, the CBO analysis explains quite well why CBO/JCT estimates of the effects of a lower corporate tax rate on revenues are worthless.

Richard Rubin wrote that “independent analyses show economic growth can’t cover all the costs of rate cuts.” But the estimates in the Table, which he cites, pretend economic growth can’t cover a single dollar of those badly estimated costs. Besides, as the CBO explains, the effect of tax rates on revenues involves much more than just economic growth.

Tax Foundation economist Alan Sloan figures that “for a corporate income tax cut to 15 percent to be self-financing [over 10 years], it would have to raise the level of growth to 2.8 percent on average,” or 0.9% faster than the 1.9% the CBO projects. A 2.8% growth rate doesn’t seem ambitious compared to the 1947–2006 average of 3.6%. Yet the Tax Foundation “model predicts something more like 0.4 percent over the budget window: a sustained period of 2.3 percent growth instead of 1.9 percent growth.”

This is an example of what Mr. Rubin meant by independent analysts predicting that “economic growth can’t cover all the costs.” Yet faster economic growth would cover nearly half the cost, in Sloan’s estimation. CBO/JCT static revenue estimates, by contrast, always assume no effect at all. Whether tax rates are doubled or cut in half, JCT revenue estimates will pretend GDP growth remains unchanged.

Tax Foundation estimates of the revenue feedback from faster GDP growth are a huge improvement over static JCT estimates, yet they too remain incomplete. They do not account for microeconomic “elasticity of taxable income” of the sort the CBO wrote about–such as shifting income and/or investment abroad, setting up pass-through entities, and maximizing deductions for interest and office expenses.

My previous blog noted that Treasury Department economists find the elasticity of corporate taxable income is 0.5 for smaller corporations, so when the tax rate goes down reported taxable income goes up. A paper for the Center for European Economic Research finds a higher 0.8 elasticity for multinationals: “Hence, reported profits decrease by about 0.8% if the international tax differential [e.g., between U.S. and foreign rates] increases by 1 percentage point.”

Lowering the super-high U.S. corporate tax rate will not reduce revenues from corporate and other taxes by nearly as much as crude rules of thumb may suggest, if revenues decline at all. And the reason is not entirely the result of greater investment, entrepreneurship, and economic growth, but also a reduction in myriad wasteful ways of avoiding this country’s uniquely dispiriting business tax.