The American economy is closing down rapidly from both voluntary and mandatory business closings. It is not just restaurants, but also manufacturing, construction, recreation, travel, and many other industries that are shuttering operations.

If this continues, there will be a massive plunge in incomes, and tens of millions of people will not be able to meet basic expenses such as rent and food. Policymakers are acting quickly to slow the virus spread, but I fear they are shuttering too much of the economy because we face a months-long health crisis, not a weeks-long crisis. The government does not have enough money to keep the economy afloat until a vaccine arrives, maybe a year from now.

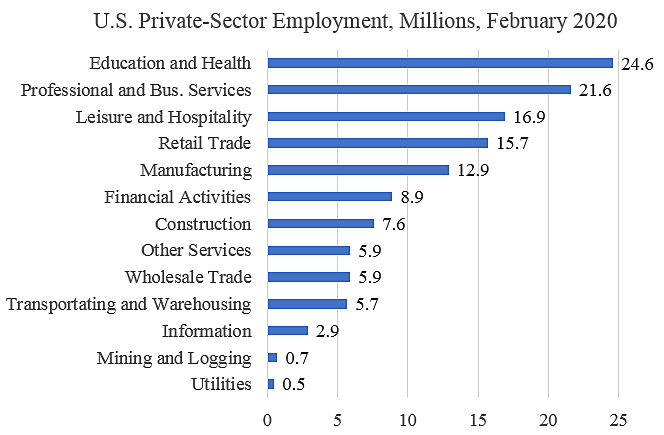

To get a sense of the massive economic shrinkage possible, the data below from BLS shows U.S. employment data in private-sector industries. I left out the nation’s 23 million government workers because they will likely continue to be paid.

The nation’s 130 million private-sector workers would have generated $16 trillion of income this year (Table 6.1D). With massive business closings, how much of that will be lost? The health part of the largest sector, health care and education, will of course remain open during the crisis. But other large sectors—such as leisure and hospitality, retail, manufacturing, and construction—are mainly closing down.

Consider a scenario where half of private-sector workers are idled for three months. That would lose the economy $2 trillion of income. Some closed businesses may continue to pay workers for a while, but when cashflows are vanishing that may not last for long.

In a Washington Post piece, a small-business owner with 75 employees expressed her fear at the impossible situation she is in. Cathy Merrill argues that even a two-month closure would be a death sentence to businesses such as hers. As she points out, she might be able to borrow to keep paying rent and labor costs, but borrowing would be risky because she doesn’t know when revenues may come back since this is an open-ended crisis. I think she’s right that small-business layoffs and bankruptcies will soar if shutdowns extend very long.

The logic of virus-fighting suggests strong measures to flatten the curve of infection in coming months. But as Merrill says, “who is going to quantify the number of deaths from unemployment stress, food insecurity, depression or lost health insurance — plus the spike in suicide rates and heart angina from the stress of being laid off or furloughed?”

Merrill suggests that officials don’t appreciate the financial vulnerability of America’s 30 million small businesses when they are ordering all-encompassing shutdowns. California has ordered a general economic shutdown except for essential services. Pennsylvania has ordered “all non-life-sustaining” businesses in the state to close. All mining, construction, most manufacturing, most retail trade, and many other industries must close based on a government central plan. These sorts of actions are very heavy handed. Governments are offering emergency businesses loans, but that won’t compensate for the massive income loss imposed if this extends for more than a few weeks.

Policymakers face tough decisions in the days ahead, but I fear that they are swinging too far toward virus control at all costs. We should be putting more weight on the economic and health damage that will be risked by extended business shutdowns.