In light of French government and Amazon threats to stamp out sellers hiking prices for coronavirus-affected products (such as face masks and hand sanitizer), my latest Telegraph piece makes the case for allowing market prices to work in the face of near-term shortages.

The case against anti-price gouging laws or restrictions is well-known. Economists generally oppose them. In this case, it’s not even clear what is happening can be described as “gouging” – a term usually reserved for high price spikes in the aftermath of disasters.

No, what we have here is good old supply and demand – the desire for these products is surging, while in the short-term supply is relatively constrained. In this environment, price rises play a useful role in deterring over-purchasing and hoarding, whilst encouraging more supply to be brought to market in future. Sharp, for example, has reoriented a TV factory to producing face masks. We’d get much more of this, or companies working overtime to meet the new demand, if there was clear profit signal to do so.

No sooner had the piece been published, but the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority announced that it was assessing whether to recommend the government introduce price controls there. No economic rationale was given for their position. UK economist Andrew Lilico points out that their own legal powers seem unlikely to cover retailers or merchants raising these prices – they usually have to find evidence of “significant market power” and “excessive pricing.” But given pharmacies, chemists, and supermarkets are fairly competitive, it’s not clear that any significant market power exists.

Perhaps as a result of the threat of government action, or concerns about a consumer backlash, many firms in the U.S. have maintained low prices, with some even discounting the sanitizer in the face of rising demand. The results are clear, with many empty shelves (see picture below). I’ve heard stories from New York about pharmacy staff running behind-the-counter black markets.

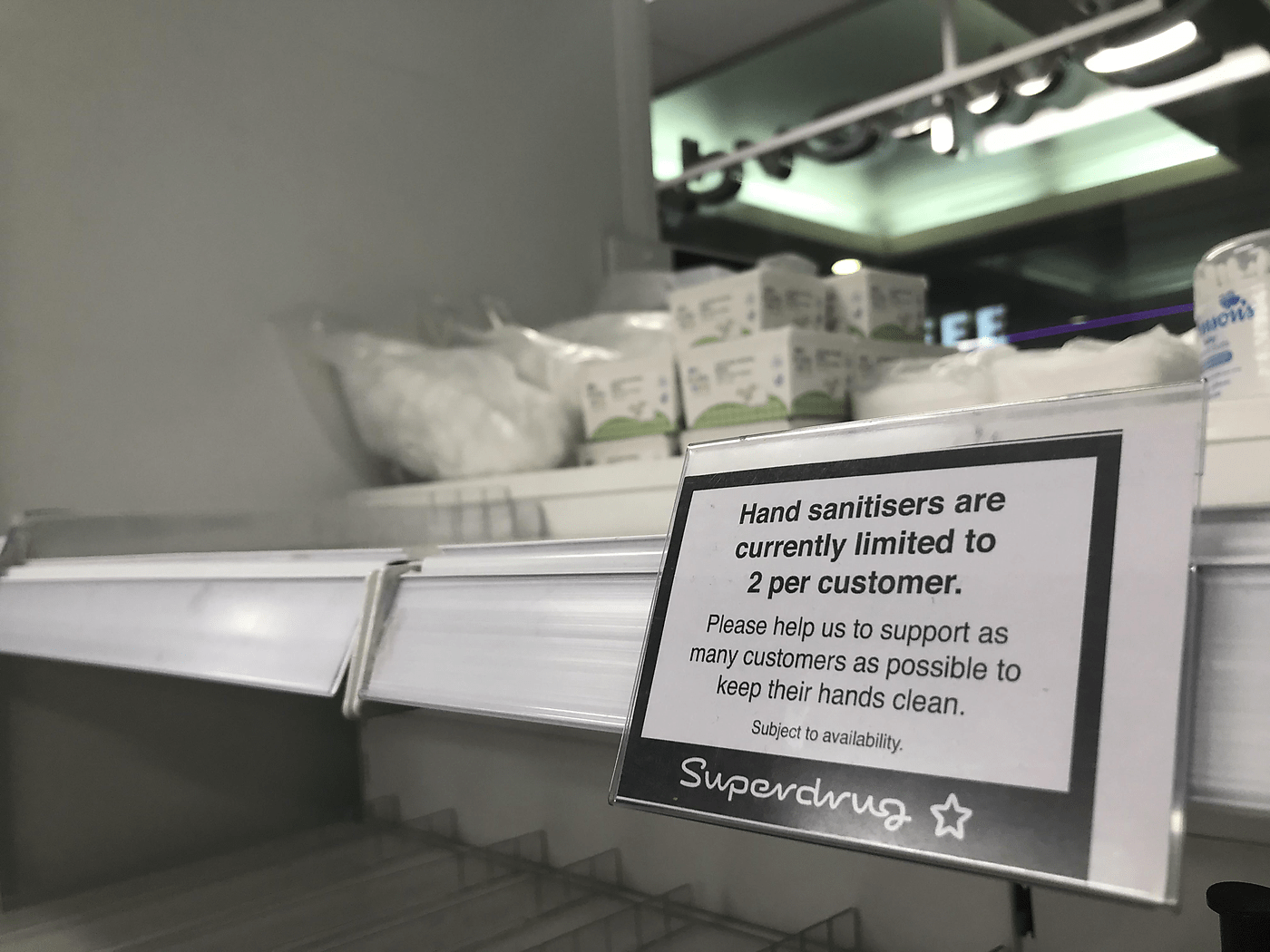

In the UK, most pharmacies are now restricting purchases to 2 per customer for hand sanitizer (see picture below), rules which can be easily circumvented by multiple store visits or asking family members to buy separately. These mechanisms are a reminder that scarce resources still need some means of being allocated, even when legal prices cease to reflect reality. Government threats of action mean they are instead being rationed according to who’s lucky enough to be around when the store gets a new delivery, or who can find a black-market seller outside of the regulator or government’s purview.

In the face of a potentially prolonged and worsening epidemic, muffling the price signals therefore risks disincentivizing much-needed supply expansions as the virus spreads. It’s bad enough that private sector firms are doing their best to keep sellers from legally serving the market. Government threats and laws would simply exacerbate the problem.